Trend following relies on a disciplined method for deciding when a market is advancing, declining, or range bound. Identifying trend direction is the state-classification component of that method. It converts noisy price movements into a structured view of market regime, which other parts of a system can use for filtering, sizing, and risk control. This article defines trend direction, explains the logic behind common measurement techniques, and shows how those techniques fit inside repeatable processes. It also addresses the risks that arise when trend estimates change or fail.

What It Means to Identify Trend Direction

Identifying trend direction is the rule-based classification of price behavior into upward, downward, or neutral states over a defined timeframe. The classification is not a forecast. It is an inference about the most probable direction of the prevailing move, given observed data and a chosen method of measurement.

In practice, the task has three parts. First, choose a timeframe, such as daily, weekly, or intraday. Second, choose a measurement rule that translates price data into a directional label. Third, define how the state will be used by the rest of the trading system, for example as a filter that permits or suppresses certain tactics, or as an input to the position sizing engine.

Because trend direction is a state variable and not an entry or exit instruction, it can be applied consistently without prescribing exact trade signals. A system can, for instance, operate long exposure only when the direction state is up, reduce exposure when the state is neutral, and allow short exposure when the state is down. The precise implementation of entries and exits remains separate.

Core Logic Behind Trend Classification

Trend direction is often conceptualized through persistence and slope. If price changes tend to continue in the same direction and the average rate of change is positive, the market is in an uptrend on that timeframe. If the rate is negative and declines persist, it is a downtrend. When neither condition holds, the market is neutral or range bound.

Any method that detects persistence and slope can be used to classify trend direction. Three broad categories are common in practice:

- Price structure rules: Classify an uptrend when price prints a sequence of higher highs and higher lows, and a downtrend when it prints lower highs and lower lows. This captures persistence directly from swing structure.

- Smoothing and slope rules: Fit a smoothed curve to price, such as a moving average or a linear regression line, and use the sign of its slope or the price’s position relative to the curve to infer direction.

- Breakout or regime rules: Infer direction from new extremes, such as price moving beyond a defined lookback range, which indicates directional persistence sufficient to reset market structure.

Each approach involves a trade-off between responsiveness and noise. Short lookbacks react quickly but misclassify more often during choppy periods. Longer lookbacks reduce whipsaws but respond slowly when a trend begins or ends. A system designer chooses parameters that reflect the intended holding period, the cost structure, and the tolerance for lag.

Timeframe Selection and Multi-Horizon Views

Trend direction is always conditional on timeframe. A market can be in a weekly uptrend while appearing sideways on a daily chart and declining on an intraday chart. The classification rule should match the horizon of the strategy module that will consume it. When a system integrates several horizons, the design must specify how they interact.

Two common patterns illustrate the choices:

- Single-horizon classification: Use a daily trend state to control a swing strategy that also operates on daily bars. The advantages are conceptual clarity and straightforward testing.

- Multi-horizon filter: Use a weekly trend state to define broad market regime, then apply a daily trend state to fine tune risk. For example, long exposure might be permitted only when the weekly state is up and the daily state is not down. This reduces conflict between horizons but increases complexity and lag.

Whichever approach is chosen, consistency is essential. The same rule should be applied through time without discretionary overrides. If a multi-horizon design is used, the interaction rules must be explicit, such as precedence when states disagree and the frequency with which states are refreshed.

Measurement Methods in Detail

Price Structure: Highs and Lows

Defining an uptrend as a sequence of higher highs and higher lows aligns with classical technical analysis. The advantage is transparency. The classification follows the tape without reference to transformation or smoothing. The challenge is operationalizing what constitutes a swing high or low, which requires a rule for detecting pivots and ignoring minor fluctuations. Small changes in the pivot definition can meaningfully alter the classification, especially in volatile or mean-reverting regimes.

Smoothing and Slope

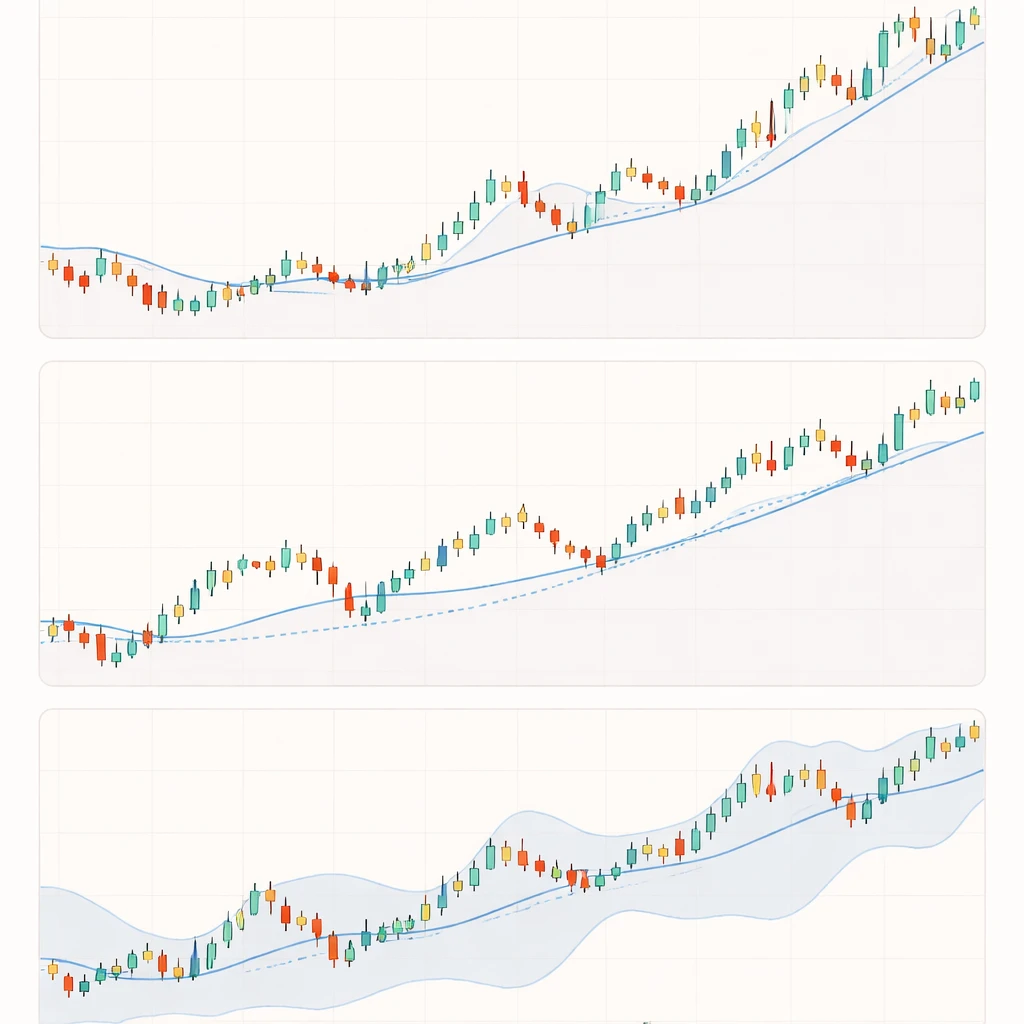

Smoothing techniques convert noisy price data into a tractable estimate of level and slope. Simple moving averages, exponential moving averages, and linear regressions are common choices. Direction can be inferred using the sign of the slope, the rate of change of the smoothed series, or the relative position of price to the smoother. For example, if the slope of a chosen moving average is positive over the past several observations and price tends to remain above it, one can classify an uptrend on that timeframe.

The primary benefit of smoothing-based classification is stability. The cost is lag. Smoothers can also underestimate emerging reversals when volatility compresses, which can leave the classification slow to update after turning points. Parameter selection, such as lookback length and smoothing type, controls the balance between lag and noise.

Breakouts and Regime Shifts

Breakout-based classification assumes that new extremes relative to a recent range indicate directional persistence. If price exceeds a lookback high, the direction is up until evidence to the contrary emerges. A lookback low breach suggests the opposite. Breakout rules measure what many trend followers care about most, which is commitment beyond the recent equilibrium. The drawback is sensitivity to volatility regime. In quiet markets, modest moves can trigger frequent state changes. In highly volatile markets, the same rules can lag significantly because ranges are wide.

Volatility-Adjusted Filters

Volatility is integral to classification because it affects the distinction between trend and noise. A mild positive slope accompanied by low volatility may deserve more weight than the same slope in a turbulent market. Volatility-adjusted channels or bands, built from an average true range or standard deviation, attempt to scale signals by the prevailing noise level. Direction can then be classified by the side of the channel that price occupies or by the drift of the channel midpoint.

Strength Qualifiers

Indicators that do not set direction can still qualify it. A directional movement measure or other trend strength metrics can be used to label states as strong or weak once direction is set by a separate rule. The classification then has two dimensions, the sign of trend and its intensity. This can be helpful for sizing modules or when a system includes tactics that perform better in strong trends than in weak trends.

Integrating Trend Direction Into a System

Trend direction becomes useful once it is embedded in a structured workflow. A typical architecture includes a data layer, a classification layer, a decision layer, and a risk layer. The data layer prepares clean inputs, including corporate action adjustments and synchronized timestamps. The classification layer sets the state based on a fixed rule and stores it as an observable attribute. The decision layer contains tactics that refer to the state without modifying it. The risk layer converts decisions into position sizes within predefined limits.

For auditability, each layer should record its outputs along with the inputs used. This provides a traceable history of state changes and reduces the possibility of lookahead errors or parameter drift. Version control for parameters and clear changelogs help maintain the integrity of backtests and live operations.

Example: A High-Level Trend Filter

Consider a hypothetical daily system that operates a set of long-only tactics in equities. It uses a weekly trend classification as a gate. The weekly state is set by a smoothing-and-slope rule applied to weekly data. When the weekly state is up, the daily module is permitted to express long exposure within risk limits. When the weekly state is down or neutral, the module reduces or suspends exposure as defined by a separate risk policy. No exact entries or exits need to be specified to describe the concept. The filter simply controls whether long tactics are available, leaving timing to other modules.

Now extend the design to multiple assets. Each asset has its own daily classification for local decisions, and a broad market index has a separate weekly classification for portfolio-level gating. This architecture lets the system respond to asset-specific trends while respecting the general market regime. Diversification across assets and timeframes reduces reliance on any single classification.

Risk Management Considerations

Classifying trend direction does not remove risk. It redefines and concentrates certain risks while attempting to reduce others. The main concerns are whipsaw risk, regime shift risk, parameter instability, and cost drag.

- Whipsaw risk: During sideways conditions, direction labels may flip frequently. Each flip can incur cost if it triggers exposure changes. Longer lookbacks or volatility filters can reduce flips but increase lag.

- Regime shift risk: Large reversals can occur after extended trends. Smoothing-based classifiers react slowly by design. The system must tolerate drawdowns that occur during transition periods or use independent risk controls that limit exposure while the classification catches up.

- Parameter instability: Direction rules calibrated to one decade can perform differently in another. Robustness checks, out-of-sample tests, and walk-forward processes help assess whether a chosen rule is sensitive to nonstationary market behavior.

- Cost drag and turnover: Frequent state changes increase trading costs when the state controls exposure. Cost-aware design places limits on how often exposure can change, sets minimum holding horizons, or uses buffers around thresholds to reduce unnecessary flips.

- Volatility scaling and sizing: Trend direction says nothing about how much risk to take. Position sizing can reference volatility estimates, maximum loss constraints, or portfolio-level drawdown budgets that operate independently from the direction classifier.

Risk management should be codified so that the system behaves consistently during stress. This includes predefining how to handle data gaps, delayed prices, and extreme prints. It also includes specifying refresh frequency for the classification to avoid intraperiod changes that were not intended.

Lag, Noise, and the Design Trade-off

All trend direction methods face the same interplay between lag and noise. A faster classifier reduces delay when a trend begins but reacts to transient moves. A slower classifier reduces false signals but leaves more capital engaged or sidelined during turns. The appropriate balance depends on the horizon, costs, and the opportunity set.

Practical design uses buffers and confirmation windows. For instance, rather than switching direction on a single observation, the rule can require several consecutive confirmations or a minimum deviation from the threshold. This does not prescribe trade signals. It simply defines when the state is allowed to change, which reduces the impact of random fluctuations near decision boundaries.

Data Quality and Implementation

Accurate classification depends on accurate data. Adjusted prices should be used for instruments affected by corporate actions. For futures, continuous series should be constructed using a consistent roll methodology that avoids artificial jumps around contract changes. Missing data and outliers require explicit treatment rules, such as forward-filling within limits or excluding observations that fail validation tests. The implementation should prevent lookahead by ensuring that only information available at the classification timestamp is used.

Time alignment across assets is also important. When combining a weekly classifier with daily tactics, the weekly state should update on a clear schedule and remain fixed until the next update. If intraday execution is involved, the daily classification must be defined relative to a specific close or snapshot time to avoid unintended mid-session changes.

Evaluation Metrics and Diagnostics

A trend direction classifier can be evaluated without defining trades by studying its state history and transitions. Useful diagnostics include:

- State persistence: The distribution of run lengths for up, down, and neutral states. Excessively short runs indicate noise sensitivity.

- Transition timing: The delay between major market turning points and state changes. Excessive delay suggests that the rule is slow for the intended horizon.

- Agreement across methods: The degree to which price structure, smoothing, and breakout classifiers agree. Persistent disagreement can flag parameter mismatches or regime changes.

- Cost-implied turnover: The expected frequency of exposure changes when the classifier is used as a filter, combined with an estimate of trading costs. This frames the feasibility of the approach in live conditions.

- Cross-asset consistency: Whether the classifier behaves similarly on assets with different volatility profiles. Large differences can indicate the need for volatility scaling or asset-specific parameters.

When the classifier is embedded in a complete strategy, performance attribution can separate the contribution of the trend filter from the contribution of entry, exit, and sizing modules. That separation helps determine whether the direction labels meaningfully improve the distribution of outcomes or simply reduce activity.

Failure Modes and Edge Cases

Any systematic definition of trend direction will struggle in certain conditions. Three edge cases are common:

- Compressed ranges: Low volatility with small directional drift can produce frequent label changes if thresholds are tight. Buffers and confirmation windows help.

- Volatility spikes without structural breaks: Sharp moves that stay inside a broader range can prompt premature state changes. Volatility-adjusted thresholds can reduce sensitivity to these bursts.

- Gaps and discontinuities: News-driven gaps can invert the classification between sessions. A rule for handling gaps, such as deferring classification until a full bar closes, limits unintended midstream changes.

Monitoring tools can track how often these conditions occur and whether classification behavior matches design expectations. If not, the parameters or methods may need recalibration using robust validation practices.

Parameter Robustness and Governance

Trend direction rules should be robust to modest parameter changes. If small adjustments to lookback length or smoothing type lead to large differences in state history, the approach may be overfit to noise. Robustness can be assessed by testing parameter grids, performing out-of-sample checks, and applying the classifier to multiple assets or time periods. The goal is not perfection, but stability across reasonable variations.

Governance covers how changes are made over time. Document the rule, the data used, and the rationale for parameter settings. Define a process for proposing changes, including the evidence required and the testing protocol. Record each change in a log, along with the expected effects. This level of discipline is particularly valuable for institutional contexts, but even individual researchers benefit from a clear audit trail.

How Trend Direction Fits Into Repeatable Trading Systems

A repeatable system separates responsibilities. Trend direction focuses on state classification. Entry and exit logic focus on timing within that state. Risk modules convert decisions into controlled exposure. Portfolio construction allocates across assets and tactics according to limits and diversification rules. By isolating trend direction from execution decisions, the system can be tested and improved module by module.

For example, a portfolio might include a long-only equity module gated by a broad market trend state, a cross-asset trend module that reacts to individual futures trends, and a defensive allocation module that reduces leverage when several weekly states are down simultaneously. All of these use trend direction as an input without relying on a single fragile definition. Consistency and documentation ensure that what is tested is what is traded.

Practical Notes on Testing

Before a trend classifier is used live, it should be tested in a way that reflects operational constraints. Using realistic bar timing and cost assumptions prevents optimistic bias when the state controls exposure. To guard against overfitting, the test should include multiple historical periods with different volatility regimes and macro conditions. Walk-forward validation, where parameters are set using a rolling training window and evaluated on subsequent data, provides evidence about stability when the future does not resemble the past.

It is also useful to stress test with synthetic data that contain known properties, such as embedded trends with varying noise levels. If the classifier cannot identify direction in synthetic series where the ground truth is known, it is unlikely to perform well on real data. Conversely, a method that only works on synthetic series may be too idealized for live markets.

High-Level Illustration Without Prescribing Signals

Imagine a ruleset that classifies weekly direction using a smoothed slope, daily direction using price structure, and intraday direction using a breakout rule. The system specifies that long equity exposure is allowed only when weekly and daily states are up. If either state is neutral, exposure is reduced by a prewritten risk policy. If either state is down, the long-only module remains inactive until conditions change. Execution details, entries and exits, and asset choices remain outside this description. The classifier does not predict. It merely governs which modules can act, and to what degree.

Such a configuration highlights a common benefit of state classification. It reduces the number of decisions that require precise timing and replaces them with a bounded set of regime responses. The design trades some sensitivity to quick reversals for consistency and clarity in portfolio behavior.

Cost Awareness and Operational Constraints

Live systems face practical constraints. Some assets trade with wider spreads, and some sessions offer less liquidity. Classifiers that change state near illiquid times can increase costs or slippage. A simple operational rule, such as updating the classification after a specific close and acting only during predefined windows, reduces these frictions. Similarly, data amendments or corporate actions sometimes arrive after the fact. The system should specify whether classifications will be restated or left as originally computed to preserve an auditable record.

Extensions and Variations

Trend direction classification can be extended beyond single assets. For equity portfolios, advance-decline figures or other breadth measures can summarize whether a majority of constituents participate in an uptrend. For currencies or commodities, relative strength across the universe can serve as a higher-level trend proxy. Direction can also be combined with seasonality or macro filters, provided each component is validated independently.

Another extension is to classify trend confidence. Instead of a binary label, the classifier can output an up probability, a down probability, and a neutral probability that sum to one. Probabilistic labels integrate naturally with position sizing frameworks that scale risk in proportion to conviction while respecting maximum limits. The probabilities must be estimated with care to avoid overstating precision, especially in short samples.

Ethos of Conservative Design

Despite the appeal of complex models, simple and transparent classification often proves more reliable in live use. Fewer moving parts mean fewer ways to fail. A conservative ethos favors rules that are easy to explain, grounded in observable behavior, and consistent across time. Complexity should be added only when it provides demonstrated benefits that outweigh the costs in terms of fragility and maintenance.

Key Takeaways

- Identifying trend direction is a rule-based state classification of price behavior by timeframe, not a forecast or a trade signal.

- Methods center on price structure, smoothing and slope, and breakouts, each with a trade-off between responsiveness and noise.

- Risk management remains separate, addressing whipsaws, regime shifts, parameter stability, and costs through independent controls.

- Embedding the classifier in a layered system clarifies responsibilities and enables testing and governance without discretionary overrides.

- Robustness, data quality, and cost-aware implementation determine whether a direction classifier remains reliable in live conditions.