Breakout strategies attempt to capture directional movement after price pushes beyond a well-defined boundary such as a prior high, a consolidation range, or a volatility band. Markets do not move in straight lines, and many apparent breakouts do not persist. A false breakout occurs when price moves beyond a level that would normally signal continuation, only to return within the prior range shortly after. Understanding this pattern matters because it affects both breakout-following and mean reversion approaches, and because it is common across liquid markets and timeframes.

The concept is not a prediction device. It is a descriptive label for a recurring sequence of events that can be integrated into structured, rule-based systems. The value lies in clarity: define what constitutes a breakout and what constitutes failure, decide how to validate context, and attach explicit risk controls. Without this structure the term becomes a vague narrative after the fact.

Defining a False Breakout

A precise definition requires three ingredients: a level, an excursion beyond that level, and a return that negates the excursion. The level might be a recent swing high, a multi-day range boundary, a Donchian channel, or a prior session high or low. The excursion is the initial move beyond the boundary. The negation is a subsequent move that places price back inside the prior range within a limited amount of time or distance.

Two clarifications help avoid confusion:

- False breakout versus pullback: In a pullback, price breaks out and then retraces while remaining above the breakout level in an up move or below it in a down move. The trend attempt is intact. In a false breakout, price moves back inside the range, which nullifies the structural signal.

- False breakout versus retest: A retest touches the level and holds. A false breakout violates the level and fails to hold. The defining feature is loss of acceptance beyond the boundary.

Definitions are timeframe dependent. A false breakout on a 5-minute chart may be noise on a daily chart. System design needs to fix the timeframe at the outset and keep the definition consistent.

Why False Breakouts Occur

Markets are auction processes. Price explores new areas to find liquidity. The moment price pushes beyond a widely observed level, resting orders on both sides are activated. The specific mechanisms vary, but several forces are frequently present:

- Liquidity seeking and stop pools: Breaks of highs or lows often trigger stop orders from participants who were positioned against the level. Those stops supply liquidity to counterparties. Once the resting liquidity is consumed and new takers do not continue the move, price can revert back into the prior range.

- Information asymmetry: News or rumors can spark an impulsive push. If the incremental information does not justify acceptance at the new level, order flow fades and price retreats.

- Volatility regime shifts: In quiet regimes, small moves can appear significant without follow-through. In high-volatility regimes, overshoots and whipsaws are common because the distribution of intraday ranges is wide.

- Session structure and microstructure: Opening auctions, scheduled economic releases, and batch order imbalances can produce one-time pushes that are not sustained once initial flows subside.

These drivers do not imply predictability. They motivate a structured way to classify and test the phenomenon.

How False Breakouts Fit Within Structured Trading Systems

False breakouts can play two distinct roles within a system:

- As a primary pattern: A system can be designed to engage when a breakout attempt fails under specified conditions. The logic is usually mean-reverting back into the prior range or toward a range midpoint.

- As a diagnostic filter: A breakout-following system can include rules that avoid or delay action when early signs of failure appear. The goal is to reduce exposure to low-quality breakouts.

Regardless of role, the same architectural elements are useful:

- Universe and timeframe: Specify assets and the bar interval. Consistency is essential for meaningful evaluation.

- Level construction: Define how the breakout boundary is drawn. Use mechanical rules such as highest high over a lookback, a recent swing structure, or a session extreme.

- Breakout definition: State what constitutes an excursion beyond the level. For example, an intrabar print beyond the boundary versus a bar close beyond it are different signals.

- Failure definition: Describe the conditions that place price back inside the range within a limited window. The window can be time based or distance based relative to volatility.

- Execution protocol: Outline when and how orders are evaluated after the failure is detected. Avoid discretionary overrides if the goal is reproducibility.

- Risk controls: Specify invalidation, position sizing method, and exit logic that cap downside and standardize behavior across signals.

Identifying Levels and Context

False breakout logic depends on coherent levels. Several mechanical methods are common in research settings:

- Range-based levels: Define a consolidation by consecutive bars with overlapping highs and lows, or use bands such as Donchian channels over a fixed lookback.

- Swing points: Identify recent local highs and lows using pattern rules for pivots. The more tests a level has seen, the more visible it tends to be to market participants.

- Session extremes: Prior day high and low, opening range, or weekly extremes provide stable references on intraday frames.

- Anchored measures: VWAP and rolling volume profiles can highlight areas where acceptance has concentrated. Breaks from these zones may be more informative.

Context matters as well. Systems commonly evaluate:

- Volatility: Normalization by recent true range helps compare moves across regimes. A one-point move has different significance when average range is small versus large.

- Volume: Relative volume can indicate participation. Some failures occur on thin pushes with little sponsorship.

- Trend state: A higher-timeframe trend may influence the persistence of a breakout. A counter-trend break is more vulnerable to failure.

- Time of day or event proximity: Breakouts around scheduled releases are fragile once the one-time order burst dissipates.

Objective Detection of Failure

A system needs unambiguous logic to detect both the breakout and its failure. Without providing exact numeric signals, the following elements indicate how objective rules can be formed:

- Excursion criteria: Require price to print or close beyond the defined boundary by more than a minimal buffer that accounts for noise relative to recent volatility.

- Failure criteria: Within a limited number of bars or within a preset normalized distance, require price to be back inside the prior range. Some systems use the close reentering the range. Others consider an intrabar reentry combined with a weak close.

- Magnitude filters: Assess how far the excursion traveled before returning. Very shallow excursions followed by quick reentry can indicate poor sponsorship. Deep excursions that fully reverse may indicate a more forceful rejection.

- Volume behavior: Observe whether relative volume expanded on the excursion and then dried up, or whether volume spikes accompany the reentry. Each pattern implies different order flow dynamics.

- Time decay: The longer price remains beyond the boundary without returning, the less likely the event will be classified as failure in many frameworks.

These items can be coded with thresholds chosen through out-of-sample testing. The aim is not to optimize for the past but to prevent ambiguity in live evaluation.

Strategy Archetypes Built Around False Breakouts

The same detection logic can support multiple archetypes. A research process typically evaluates several families and selects those that align with the system’s objectives and constraints.

- Fade back into the range: After failure, assume a tendency toward mean reversion or toward the range midpoint. This approach often seeks short holding periods and relies on tight invalidation relative to the range boundary.

- Re-breakout confirmation: Wait for price to reassert the original breakout direction after an initial failure. The assumption is that early failure cleared opposing positions and improved the odds of subsequent acceptance.

- Continuation filter for trend systems: Use failure detection as a filter. If a breakout shows characteristics of failure, reduce engagement size or require additional confirmation before following the move.

- Range expansion diagnostics: Treat false breakouts as evidence that the market is not yet ready to expand. The system then focuses on later signals when conditions change, such as volatility compression followed by a stronger push.

These archetypes differ in holding period, sensitivity to costs, and drawdown profile. They also respond differently to volatility regimes, which suggests that diversification across families can be productive for research purposes.

Risk Management Considerations

Risk management is central to any use of false breakout logic. Three dimensions are particularly important: invalidation, sizing, and exits.

Invalidation: Define where the thesis is wrong in structural terms. In a fade-back concept, invalidation often sits beyond the level that price failed to accept. In a re-breakout concept, invalidation relates to the loss of acceptance in the renewed direction. Structural invalidation reduces discretion and prevents escalation of small losses into large ones.

Volatility-normalized sizing: Position size is commonly tied to recent range or variance so that risk per trade is stable across quiet and volatile periods. Normalization avoids oversizing in calm regimes and undersizing in turbulent ones.

Exit logic: Systems can include time-based exits to prevent capital from being trapped in sideways ranges. Profit-taking rules can be anchored to range features such as midpoints or opposing boundaries. Trailing concepts are sometimes used when re-breakouts develop into trends. Each exit choice changes the distribution of outcomes and the correlation to other strategies in a portfolio.

Additional considerations include:

- Clustering risk: False breakout opportunities often cluster around the same assets and times, such as after macro releases. Aggregate exposure limits help prevent concentration.

- Slippage and liquidity: Failures can develop quickly. Market impact and partial fills must be reflected in research. Conservative cost assumptions are prudent.

- Regime shifts: When broad volatility or liquidity conditions change, recent performance characteristics may not persist. Systems can include regime-aware throttles or pause rules.

- Risk of ruin: Estimating worst-case sequences through stress tests and Monte Carlo resampling helps align position sizing with capital preservation goals.

Practical High-Level Example

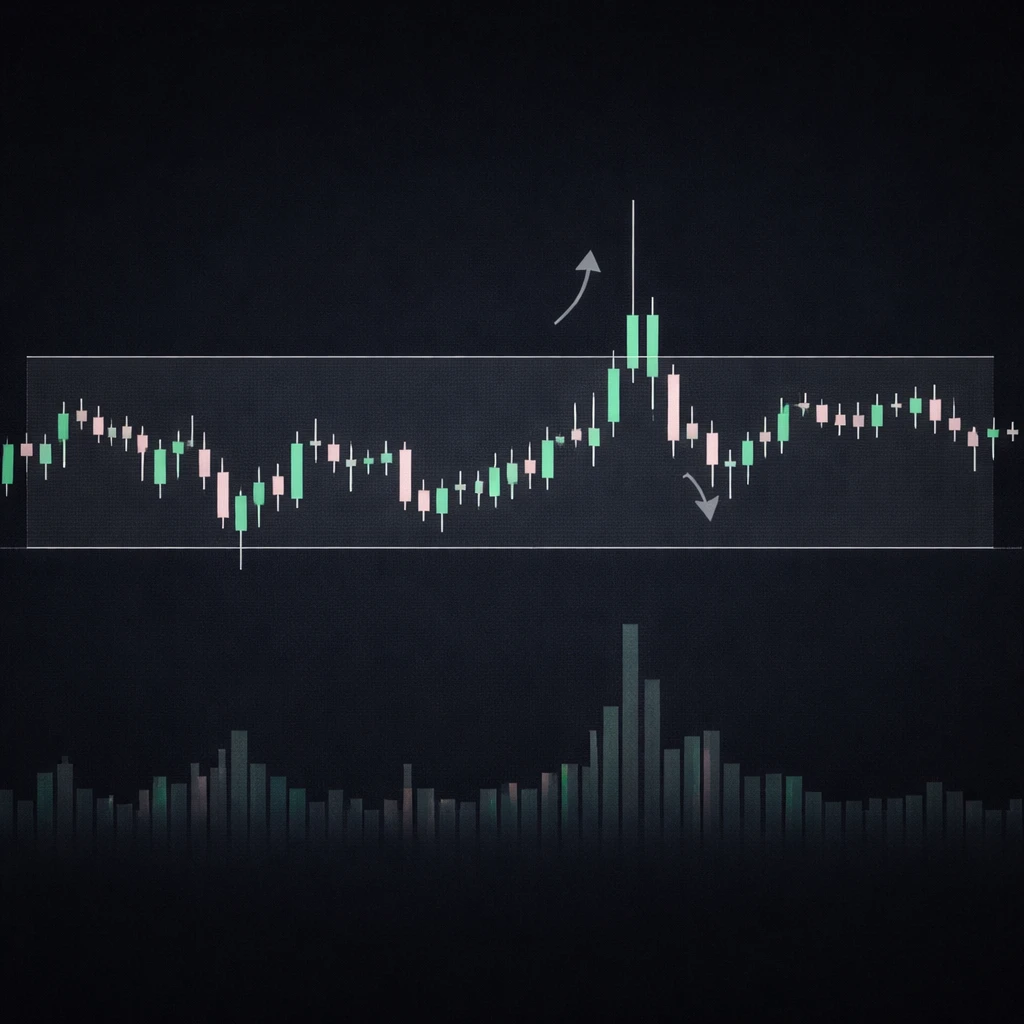

Consider a large-cap equity that has traded in a well-defined multiweek range. Traders observe the range highs, and on a day with strong opening momentum price pushes slightly above that boundary. Volume increases, but after the first thrust the order flow cools. By the next measurement interval, price has returned inside the prior range and closes there. That sequence satisfies a common definition of a false breakout.

How might a structured system use this information without prescribing exact trades or prices?

- Fade archetype: The failure is treated as evidence of rejection. A fade framework expects mean reversion into the range. Invalidation would typically be near the area that would indicate renewed acceptance, while profit-taking might be aligned with a range midpoint or a prior area of acceptance.

- Re-breakout archetype: The system waits to see if the instrument can later reestablish acceptance beyond the same boundary with stronger sponsorship. The earlier failure serves as a filter that requires a cleaner second attempt, potentially with a different volume and volatility profile.

- Breakout filter: A separate trend-following module may skip the initial break because failure criteria were met, thereby avoiding participation in a low-quality signal. It may resume attention only if subsequent conditions improve.

This example illustrates how a single observation can feed distinct modules within a multi-strategy architecture. Each module has explicit rules for detection, risk, and exit, and each is evaluated on its own merits before combination in a portfolio.

Backtesting and Evaluation

Evaluating false breakout logic requires care. The pattern is prone to narrative bias, so research discipline is essential.

- Data quality and survivorship: Use data that includes delisted names when studying equities, and verify corporate action adjustments. Clean intraday data if the timeframe is short.

- Lookahead and peeking: Ensure that a bar’s classification relies only on information available at the decision time. For example, using the closing price of a bar to define failure implies that action can only occur after that close.

- Multiple testing: Many thresholds can be tried. Protect against overfitting by using out-of-sample evaluation, cross-validation on rolling windows, or simple rules that generalize across assets and regimes.

- Cost modeling: False breakout sequences can flip direction quickly. Include conservative assumptions for slippage and commissions. Test sensitivity to costs, since edge can disappear with small changes.

- Metrics: Inspect expectancy, hit rate, payoff ratio, and drawdown depth and duration. Examine holding period distributions and performance by regime to understand when the concept contributes and when it does not.

Visual audits are useful as a secondary check. Sampling random signals and plotting them on charts helps verify that the logic identifies the intended structure and not unrelated noise.

Behavioral and Psychological Dimensions

False breakouts play on common behavioral responses. For breakout followers, buying new highs or selling new lows can feel uncomfortable. The discomfort can amplify if the move immediately reverts. For mean reversion traders, stepping into a reversal requires confidence that the rules have been met and risk is capped.

Structured processes mitigate these pressures. A checklist approach defines the level, the breakout, the failure, and the exit before any signal occurs. By the time the sequence unfolds, the system either acts or does not act based on predefined logic. The aim is to reduce inconsistent responses that stem from surprise or regret.

Common Pitfalls and Systematic Safeguards

- Ambiguous levels: If levels are drawn subjectively, two analysts may classify the same move differently. Mechanical definitions reduce ambiguity.

- Ignoring regime context: A threshold that works in quiet markets may fail in high-volatility regimes. Volatility normalization and adaptive filters help maintain comparability.

- Overreliance on single cues: Volume spikes or large wicks alone are not sufficient. Combining price, time, and participation features produces more stable detection.

- Curve fitting: Optimizing the pattern to specific historical episodes creates fragile rules. Simplicity and parsimony improve robustness.

- Event risk: Breakouts that occur around earnings or macro releases behave differently. Systems can exclude scheduled event windows or apply separate logic.

Extensions Across Markets and Horizons

The false breakout concept is portable, but details matter.

- Intraday futures: Exchange sessions and roll schedules influence levels and cost structures. Opening range definitions are often central.

- Foreign exchange: Continuous trading and session overlaps change the relevance of time-of-day filters. Liquidity tends to concentrate at specific hours that shape breakout quality.

- Cryptocurrencies: Around-the-clock trading and episodic liquidity gaps produce frequent overshoots. Cost modeling is critical due to slippage during fast reversals.

- Options overlays: Some systems pair underlying signals with options structures to shape payoff asymmetry. This changes risk and cost dynamics and requires separate option-specific research.

Placing False Breakouts Within a Broader Framework

Viewed in isolation, a false breakout is simply a failed probe beyond a boundary. Within a broader framework, it is an observable state that informs decision modules. One module may fade it, another may wait for renewed strength, and a third may use it as a quality control measure for trend entries. Portfolio design then allocates risk across modules with the aim of reducing dependency on any single market condition.

Structure is the link between observation and repeatability. When the definitions and controls are clear, the false breakout becomes a researchable input rather than a story applied after the fact.

Key Takeaways

- A false breakout is a move beyond a defined level that loses acceptance and returns inside the prior range within a limited window.

- Objective definitions require explicit rules for the level, the excursion, and the failure, with thresholds that account for volatility and time.

- False breakouts can serve as primary signals, as re-breakout setups, or as filters that improve breakout quality in trend systems.

- Risk management centers on structural invalidation, volatility-normalized sizing, time-aware exits, and controls for clustering and costs.

- Robust evaluation uses clean data, avoids lookahead bias, models costs conservatively, and inspects performance across regimes.