Volume is one of the most referenced elements in technical analysis. It is treated as a gauge of participation that can lend context to price moves, trend persistence, or potential exhaustion. Yet volume is frequently misread. The same histogram that appears straightforward can conceal data construction choices, session boundaries, mechanical prints, or market microstructure effects. Misinterpreting volume data means drawing inferences about supply and demand from volume bars or volume indicators without fully accounting for how that data was generated or what non-informational forces shaped it.

This article defines misinterpretation in precise terms, shows how it appears on charts, explains why market participants pay attention to these patterns, and provides practical chart contexts that illustrate how a volume signal can mislead. The goal is to improve interpretation, not to prescribe strategies or recommendations.

What Misinterpreting Volume Data Means

Misinterpreting volume data is the analytical error of reading the magnitude, timing, or pattern of executed trades as evidence of directional conviction when that volume is influenced by factors unrelated to new information or sustained liquidity shifts. The error often arises from one or more of the following:

- Confusing mechanical volume events with informed trading, such as open and close auctions, index rebalances, or block prints.

- Ignoring the data pipeline, including which venues are included, whether pre and post-market trades are present, and how late prints are stamped.

- Comparing volume across periods without adjusting for intraday seasonality, calendar effects, or corporate actions like splits.

- Treating indicator transformations of volume as if they were direct observations of capital flow.

- Assuming a stable relationship between volume and volatility when that relationship is regime dependent.

On charts, misinterpretation often shows up as confident readings of confirmation or divergence based on a handful of conspicuous bars, a smoothed indicator that masks calendar structure, or relative volume comparisons that ignore the nature of the session.

How Volume Data Is Generated and Displayed

Data sources and consolidation

Volume in listed equities reflects executed shares across trading venues. Vendor feeds aggregate primary exchange prints and off-exchange trades. Dark pool executions and internalized orders are often included, but timing can differ and late reporting can concentrate apparent activity in a single bar. Futures volume reflects trades on a given exchange. Many charting platforms stitch contracts to build a continuous price series, while volume may remain tied to the front contract only, creating discontinuities around roll. Foreign exchange spot does not have centralized exchange volume, so platforms often display tick volume, which counts price changes or quote updates. Crypto markets aggregate across multiple exchanges unevenly, and some venues may overstate activity. Each of these construction choices changes what a histogram means.

Understanding the construction helps explain common chart illusions. A sudden end-of-day volume spike may be the closing auction rather than a late surge of directional activity. A futures volume drop on a continuous chart can appear to signal disinterest, when in reality activity shifted to the next contract. In FX, tick volume may correlate with liquidity conditions, but it is not the same as traded quantity and can diverge during quiet algorithmic quoting or fragmented liquidity.

Session boundaries and time zones

Many charts combine regular trading hours and extended sessions. If the platform includes pre and post-market trades, thin prints outside the main session can distort relative volume calculations, especially when volume moving averages include these periods. Time zone alignment also matters. A global stock cross-listed in different regions can have overlapping sessions, and consolidated feeds may allocate volume to bars differently depending on clock conventions. During holidays, early closes and reduced hours compress activity into shorter windows, which magnifies any auction or index event.

Intraday seasonality and calendar effects

Equity volume typically follows a U-shaped intraday profile. Participation is high near the open as orders are paired, lower mid-session, and high again into the close. Comparing a 10:15 bar to a 15:45 bar without accounting for this pattern invites incorrect conclusions. Calendar effects add further structure. Month-end, quarter-end, options expiration, and index rebalancing often concentrate volume into specific intervals, especially the closing rotation. Corporate actions can mechanically raise or lower reported volume. A 2-for-1 split doubles share count, and historical volume is often adjusted, but not all vendors align adjustments the same way. Without careful attention to these details, a chart can seem to signal conviction where there is mostly schedule.

Common Chart-Based Misreadings

The confirmation trap: reading breakouts through volume

Textbook exposition sometimes frames breakouts as more credible if accompanied by above-average volume. That guidance omits several realities. First, the average matters. An average computed across a lookback that mixes regular and extended hours, or that includes atypical events, may not describe normal participation. Second, timing matters. A breakout that occurs near the open will often appear on top of elevated participation due to the daily opening rush, not necessarily new information. Third, venue matters. In fragmented markets, volume confirmation on a single feed may not reflect broad participation if large blocks execute elsewhere or are reported later.

On a chart, the trap appears as a price expansion bar with a tall volume histogram next to it. The inference is conviction. Yet the bar might coincide with index add announcements, ETF rebalances, or scheduled economic releases that changed order flow mechanically. Without separating schedule from signal, the reading can exaggerate the informational content of that bar.

Spikes from non-informational prints

Open and close auctions, midpoint crosses, and late-reported block trades can cluster a large quantity into a single bar. Auction mechanics aggregate resting orders and execute at a clearing price. The result is a high volume print that may move price little, or that may print at a price influenced by auction imbalance rules rather than continuous trading pressure. When a vendor timestamps a late block to the time of reporting rather than the time of execution, the bar that receives the print inherits a spike that does not match contemporaneous price action.

On a chart, this misinterpretation shows as a tall volume bar paired with a small-bodied candle, or a closing bar with a large spike on a day of otherwise average activity. Without recognizing auction or block mechanics, the analyst might read that bar as evidence of hidden accumulation or distribution. Often it is bookkeeping.

Volume dry-ups and the illusion of exhaustion

Low volume during a consolidation is often highlighted as an exhaustion or balance signal. The logic is intuitive. However, low participation can have many sources unrelated to trend dynamics. Midday equity volume is routinely lower because participants have already processed opening imbalances and because many intraday strategies throttle during the middle hours. Holidays, earnings blackout periods, and macro event anticipation can suppress activity. In futures, volume can shift to the next contract ahead of roll while price on a continuous chart still references the expiring contract. A dry-up there is not exhaustion. It is migration.

Indicator-driven misreads

Common volume indicators include On-Balance Volume, Accumulation Distribution, Chaikin Money Flow, the Money Flow Index, and various volume oscillators. These transform raw volume via price direction, close location, or high-low ranges. A divergence between price and an indicator can suggest waning momentum, but the indicator is a mathematical construction with smoothing and implicit assumptions. For instance, indicators that use close location relative to range can be sensitive to intraday gaps and to volatility clusters. OBV treats each up close as accumulation of the full bar volume regardless of whether the close was one tick higher or a large advance. CMF weights by the close location but assumes a symmetric relation between range and pressure that can invert during gap-heavy periods.

On charts, indicator divergences can appear notable near turning points. The problem is that a divergence can also emerge from calendar effects, uneven intraday participation, or a sequence of narrow-range bars that influence the indicator denominator more than the underlying buying or selling. Treating indicator divergence as direct evidence of institutional flow is a common misinterpretation.

Relative volume and scaling pitfalls

Relative volume compares current activity with a benchmark such as the average over N sessions or the average for the same time of day. The measure is useful when built carefully, but the comparison can be fragile. If the lookback includes earnings days, rebalances, or one-off news spikes, the baseline inflates. If the platform scales volume bars to the session high, a single outlier can compress other bars, making ordinary differences appear small. If the chart mixes pre and post-market with regular hours, a low-activity premarket bar can look elevated relative to its own tiny baseline, which can be misread as interest rather than thin liquidity.

Volume Across Markets

Equities and ETFs

Listed equities route across many venues. Closing auctions, opening crosses, and off-exchange internalization shape the profile of activity throughout the day. Corporate actions matter. Stock splits increase share counts and can make post-split volume appear higher even when dollar turnover is unchanged. Reverse splits do the opposite. Buyback programs and blackout windows shift participation without signaling trend conviction.

ETFs introduce a distinct set of interpretive hazards. ETF share volume reflects trading in the ETF itself, not necessarily flows into the underlying basket. The creation and redemption process allows authorized participants to arbitrage deviations between ETF price and net asset value. High ETF volume can arise from market making and hedging rather than directional investor flows. Conversely, low ETF volume does not imply illiquidity if the underlying market is deep and the arbitrage mechanism is functioning. Reading ETF volume as simple confirmation of broad market conviction can therefore mislead.

Futures

Futures contracts expire and roll. Near roll dates, activity migrates from the front contract to the next. On a continuous price series, this migration can appear as a sudden fall in volume or a misleading divergence between price movement and the histogram. If a platform displays volume for the expiring contract while charting the continuous price, readings around roll will be distorted. Additionally, some futures exhibit clear calendar seasonality. Energy products, agricultural contracts, and interest rate futures have reporting schedules, storage cycles, or economic calendars that concentrate volume at predictable points. Interpreting these spikes as fresh information conflates seasonality with new pressure.

FX and crypto

Spot FX is decentralized. Most retail platforms display tick volume, which counts the number of price changes rather than the number of traded units. Tick volume can correlate with liquidity and activity, especially during major sessions, but it is not a direct measure of executed size. Quiet conditions with algorithmic quoting can produce many small ticks. Conversely, during an event with wide spreads, price can jump without many individual ticks. Reading tick volume as if it were exchange volume can lead to misplaced confidence about confirmation.

Crypto markets add fragmentation and inconsistent reporting. Some venues lack robust surveillance, and wash trading has been documented historically on certain exchanges. Aggregators may include or exclude venues differently. A volume surge from a low-quality venue can inflate consolidated figures. When a chart displays combined volume without venue filters, the histogram may reflect reporting choices as much as actual participation.

Volume and Volatility: What the Relationship Can and Cannot Tell You

There is a tendency to treat volume and volatility as companions. High volume is thought to accompany large price moves, while low volume pairs with quiet ranges. The empirical link exists in some regimes, yet it is far from stable. Microstructure can invert the relationship. When liquidity providers step back, spreads widen and price jumps can occur on modest size, creating high volatility with only average printed volume. Conversely, rebalancing or index events can produce very high volume with constrained price ranges because the flow is spread across both sides at auction prices.

Event risk is another source of instability. On days with major macro releases or earnings, participants may wait for the release, resulting in low pre-event volume, then trade intensely after, creating sharp jumps that compress much of the day’s move into a narrow window. How a chart aggregates those windows drives the appearance of volume-volatility linkage. If a daily bar absorbs the whole event, it will pair a large candle with high volume. If intraday bars slice the episode into several segments, the profile can show a lull followed by a spike, which might be misread as a delayed confirmation rather than simple timing.

Regime changes and liquidity

In calm regimes with abundant liquidity, a persistent trend can advance on moderate volume because market makers comfortably warehouse risk. During stressed regimes, similar price distances can require fewer shares or contracts due to shallow order books. The same absolute volume can therefore mean different things in different regimes. Without attention to order book depth, spread behavior, and the identity of the participants likely active at that time, it is easy to over-interpret a histogram.

Volatility spikes without volume and volume spikes without volatility

Examples are common. A thin pre-market gap in an equity can print a large price change on modest traded size. A closing auction can absorb large index flows with little net range if buy and sell interest offset. Reading conviction from either case requires caution. The volatility spike without volume does not necessarily reflect strong trend pressure. The volume spike without volatility does not necessarily reflect distribution or accumulation. Both can be artifacts of the mechanics of execution.

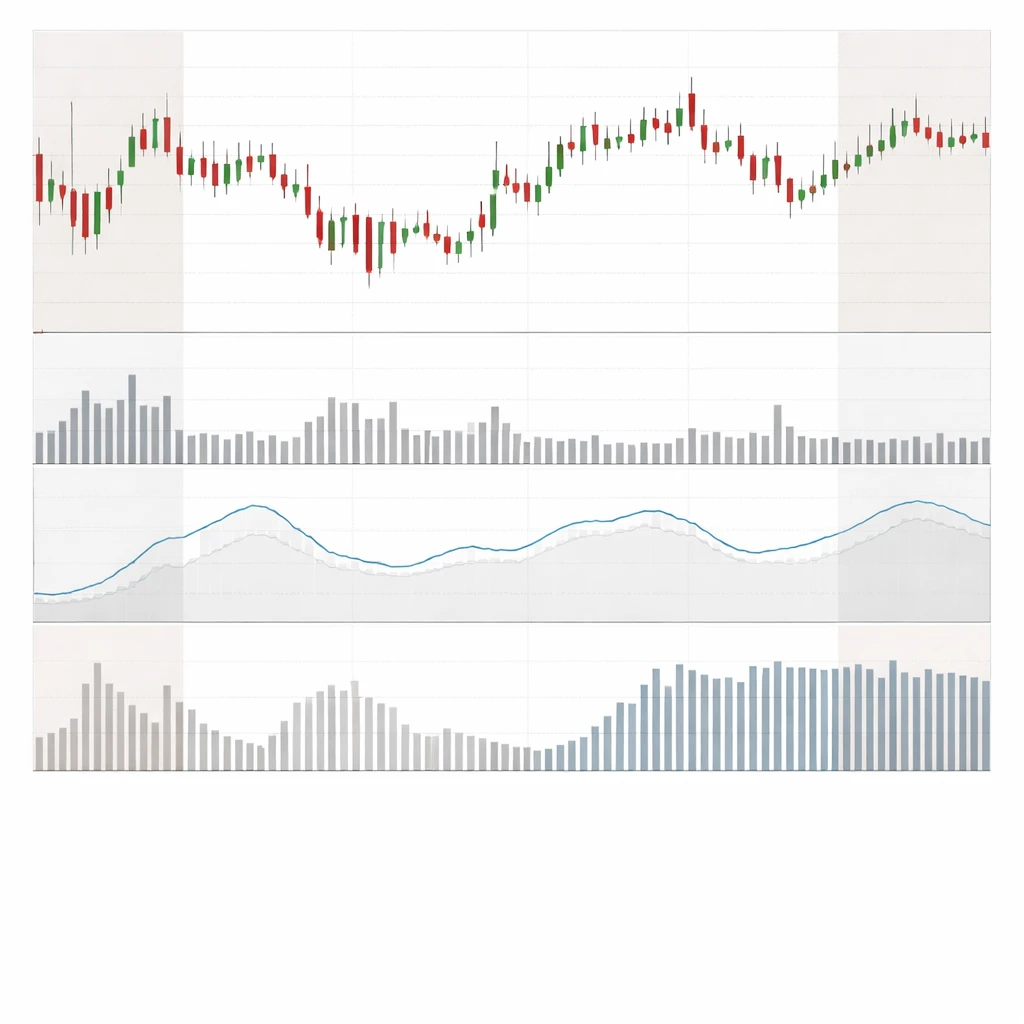

How Misinterpretation Appears on Charts

Several recurring visual motifs tend to invite overconfident readings:

- Tall single bars at session edges. Large open or close auction prints telescope into one or two bars, dwarfing mid-session activity. Without recognizing the auction, the bar looks like sudden commitment.

- Low mid-session valleys. The normal U-shaped intraday profile can be mistaken for fading interest in a trend that is otherwise intact.

- Diverging indicator lines. A smoothed volume-based oscillator can drift lower during a choppy advance and invite a narrative of stealth distribution, even as realized flows are balanced.

- Stitched series discontinuities. Around futures roll, continuous price lines mask the shift of volume to a new contract, so the histogram looks artificially depressed or inflated.

- Mixed-session comparisons. Charts that mix extended hours with regular hours produce volume bars that are incomparable across the day, which invites false relative readings.

Practical Chart Contexts

Context 1: Earnings day with open auction spike

Consider an equity with quarterly results released before the open. The pre-market prints are thin and scattered. At the opening auction, a large imbalance of resting orders is paired at a single price. The first regular-hours bar shows a small candle body because the auction price closely matches the implied pre-market equilibrium, but the volume histogram for that bar is the largest in months. An observer who reads that bar as confirmation of trend strength or a fresh influx of capital would be misinterpreting the source. The volume reflects instantaneous clearing of accumulated orders rather than ongoing demand. Subsequent bars may revert to average participation.

Context 2: ETF with high secondary-market volume

An index-tracking ETF trades at a small discount to its net asset value during a volatile session. Market makers trade ETF shares heavily while hedging with futures and baskets, keeping the discount contained. The ETF’s volume histogram is elevated all day. A chart-based reading that equates this to broad investor inflows would be inaccurate. Much of the activity is arbitrage and inventory management. The underlying index may not see corresponding primary market creations or redemptions. Here, the ETF volume bar is about price discovery and liquidity provision, not directional commitment.

Context 3: Futures rollover distortion

A commodity future approaches expiration. Two weeks prior to last trade, activity migrates to the next contract. A continuous price chart shows steady price action. The volume histogram, however, collapses on the front contract while rising in the next. If the platform displays only front-contract volume for the continuous series, the analyst sees a misleading dry-up and infers fading interest. The true interpretation is contract migration. Summed across both contracts, total market participation is stable.

Context 4: FX tick volume during a holiday

During a regional holiday, a major currency pair trades in a narrow range with fewer active dealers. Quote updates slow, spreads widen slightly, and price drifts on sporadic prints. Tick volume is low for several hours, then spikes around a European data release as quotes refresh rapidly. Reading the low tick count as exhaustion or the spike as strong new conviction would mix measurement with meaning. The observed pattern is primarily calendar driven.

Why Traders Pay Attention to Misinterpretation Risk

Volume is often used to judge whether price moves are supported by widespread participation. Incorrect inference can skew risk perception, narrative building, and model calibration. Market participants care about the risk of misinterpretation for several reasons:

- Signal validity. If a methodology treats volume as confirmation, structural spikes or troughs can distort assessments of trend persistence or reversal risk.

- Cross-asset consistency. A framework that assumes exchange-reported share volume can translate directly to FX or crypto will misapply concepts across markets.

- Model stability. Indicators that smooth volume are sensitive to lookback choices and event inclusion. Without careful construction, the same instrument can generate conflicting signals across platforms.

- Attribution accuracy. Distinguishing price impact from mechanical flow matters for understanding what moved the market and whether that driver is likely to persist.

Diagnostic Checks That Reduce Misinterpretation

The following checks do not prescribe trades. They outline observational practices that help align volume readings with the structure of the data:

- Identify the session definition. Confirm whether the chart includes pre and post-market, and whether averages use only regular hours. Compare a regular-hours-only view with a full-session view.

- Locate auctions and blocks. Note whether open and close auctions are prominent for the instrument. Inspect end-of-day bars for disproportionate spikes coupled with small price ranges.

- Account for calendar structure. Mark holidays, early closes, month and quarter ends, index events, and earnings dates. Compare volume against a time-of-day baseline rather than a flat average.

- Check corporate actions. Ensure that split adjustments are applied consistently to historical volume. Be cautious when comparing pre and post-action histograms.

- Handle futures roll correctly. Around roll, review both front and next contracts. If possible, evaluate combined volume or use a continuous series with volume that migrates alongside price.

- Understand market type. Distinguish exchange volume from tick proxies. In FX and fragmented crypto, treat volume histograms as activity proxies rather than precise measures of executed size.

- Cross-verify data sources. Where feasible, compare vendor feeds or venue filters to identify reporting anomalies or late prints.

- Contextualize with volatility. Compare volume with spread behavior, range statistics such as true range, and order book depth when available. A large price move on average volume may reflect thin liquidity.

Using Volume as Context, Not Certainty

Volume enriches price analysis by describing participation, but it is not a reliable standalone signal of conviction. The same bar can be generated by information-driven order flow or by mechanical events. The chart does not label which is which. Interpreting volume well requires an understanding of data construction, calendar and session structure, and market microstructure. When volume is treated as context rather than proof, it becomes a useful lens on market behavior that complements price and volatility without overstating certainty.

Key Takeaways

- Volume histograms reflect construction choices, session rules, and market microstructure, not just conviction.

- Common misreadings come from auction spikes, block prints, indicator transformations, and seasonality that masquerade as signals.

- The link between volume and volatility is regime dependent, with frequent examples of one rising without the other.

- Market-specific quirks, such as ETF creation-redemption and futures roll, can distort volume if not handled explicitly.

- Careful session definition, calendar awareness, and cross-checking data reduce the risk of reading noise as information.