Price symmetry is a foundational idea within price action analysis. It refers to recurring similarities in how price advances and declines unfold: swings often repeat in size, duration, slope, or visual shape. Symmetry does not promise repetition, but it provides a disciplined way to observe whether current movement resembles what just occurred. Analysts use these echoes to organize market structure, not to guarantee outcomes.

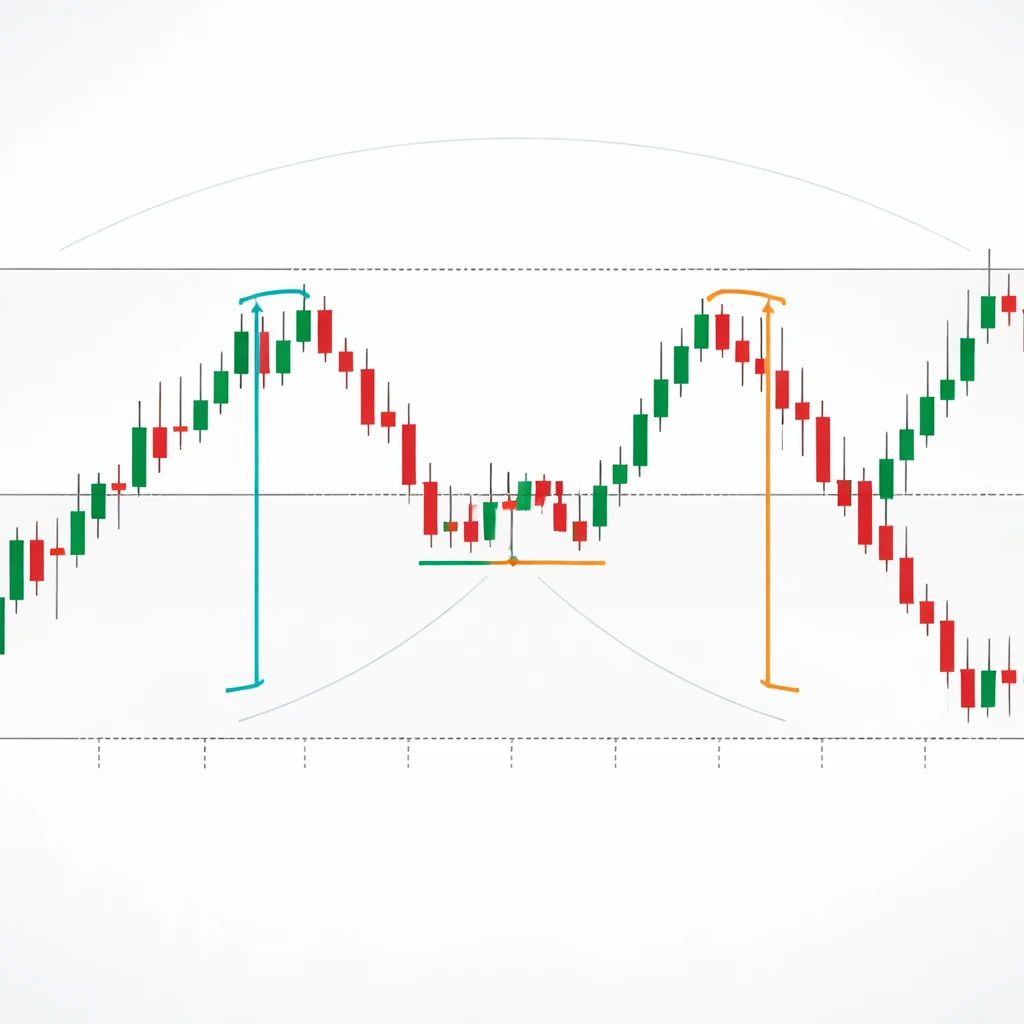

Seen on a chart, symmetry might appear as a new rally that travels about the same distance as a previous rally, or a pullback that retraces a proportion similar to earlier pullbacks. It can also show up in time: a consolidation that lasts about as long as the previous consolidation. These relationships help impose order on otherwise noisy data and support more coherent interpretations of price behavior.

Defining Price Symmetry

Price symmetry is the observable tendency for market swings to share comparable characteristics across legs or phases. The comparison can be made in points, in percentage terms, or in time units such as bars or sessions. Symmetry is often evaluated in four dimensions:

- Magnitude symmetry: comparable price distance in points or percentages between swings.

- Time symmetry: similar duration, measured in bars, sessions, or days.

- Slope or angle symmetry: similar rate of change, where distance and time align to produce a comparable incline or decline.

- Pattern symmetry: mirrored shapes such as equal legs, measured moves, or left-right balance within classical chart patterns.

Price symmetry does not claim causality. It is a descriptive framework that highlights repeated proportions and rhythms. Some observers view symmetry as a byproduct of collective behavior, reference dependence, and the tendency for market participants to react to previously significant moves.

Why Market Participants Monitor Symmetry

Market participants study symmetry to anchor expectations in observable history rather than intuition. Comparable swings suggest where reactions have occurred before, and where the crowd might recalibrate again. This is not a forecast. It is a way to articulate conditional scenarios: if the next move resembles the last in size or time, what would that imply for structure, momentum, or potential exhaustion.

Symmetry also encourages consistent measurement. Evaluating equal or proportional swings forces the analyst to define reference points, choose a unit of measure, and apply those choices uniformly. The result is less narrative drift and more transparent reasoning about chart behavior.

How Symmetry Appears on Charts

Symmetry is visible in many market environments. Several recurring contexts illustrate how it typically presents:

- Trending pullbacks: In persistent trends, pullbacks often cluster around similar depth or duration. For example, an uptrend might show repeated retracements of roughly 4 to 6 percent, each lasting several sessions before price returns to the prevailing direction.

- Equal legs in swings: Commonly described as a one-to-one or measured move, a second leg travels a distance similar to the first. After an initial rally of 12 points, a consolidation may be followed by another advance of about 12 points.

- Range rotations: In lateral markets, price oscillates between approximate boundaries, creating roughly equal up and down traverses. The distance from range midline to boundary can also repeat, creating a secondary form of symmetry.

- Left-right balance in patterns: Double tops and double bottoms illustrate magnitude symmetry at two swing extremes. Head and shoulders structures display partial left-right correspondence in shoulder height or timing, though real data rarely yields perfect balance.

- Time clusters: Consolidations may repeat similar durations. A three-week pause after a rally can be mirrored by another multi-week pause later, even if the price levels differ.

These examples are descriptive. Actual markets exhibit noise, gaps, and regime shifts that disturb perfect alignment. The analytical value lies in how often and how closely symmetry recurs, not in a single precise match.

Dimensions of Symmetry

Magnitude: Points vs. Percentages

Magnitude symmetry can be assessed in absolute points or in percentages. Point-based symmetry is common in futures or index analysis, where the instrument’s tick value and point scale have immediate meaning. Percentage symmetry often suits equities and multi-year studies where price levels drift over time. The choice of scale affects interpretation. For a stock that doubles over two years, a 5 point pullback has a different significance early in the move than later. A percentage frame normalizes comparisons across changing baselines.

Time: Bars, Sessions, and Clocks

Time symmetry focuses on how long something took. Analysts might compare how many daily bars were required for a rally versus the subsequent pullback. Intraday, the comparison might involve 5-minute bars or volume-adjusted bars. The point is consistency: use the same unit across the comparison so that durations are truly comparable.

Slope: Rate of Change

Slope symmetry integrates price and time. Two legs can share similar magnitude but differ materially in slope if one develops in half the number of bars. Similar slopes imply comparable urgency or participation. Divergence in slope indicates a change in the pace of movement, which can modify the reading of momentum without changing the absolute distance traveled.

Pattern Symmetry: Visual Echoes

Prices often trace shapes that appear balanced on either side of a midpoint. A V-shaped reversal displays a fast down leg followed by a fast up leg of similar distance. A U-shaped base exhibits more gradual left-right equivalence. Head and shoulders patterns are hybrid forms where magnitude or time symmetry is suggested in the shoulders, while the head breaks the line of symmetry to define the pattern. Recognizing pattern symmetry does not require perfection. The useful question is whether the present swing rhymes with an earlier one closely enough to inform interpretation.

Measuring Symmetry on a Chart

Symmetry analysis is straightforward once the comparison rules are set. A typical measurement sequence might resemble the following:

- Choose anchor points: Identify clear swing highs and swing lows. Consistency is critical. Use the same type of pivot identification across comparisons.

- Select the measurement unit: Decide whether to measure in points, percentages, or bars. Maintain that unit throughout the assessment.

- Measure the reference swing: Quantify the distance or duration of the first leg. Record it.

- Project the reference: From the next pivot, project an equal distance (or proportional percentage) to visualize a potential zone of symmetry.

- Compare outcomes: Observe whether price approached, matched, or exceeded the projection. Note the degree of deviation rather than only the hit or miss.

Many charting platforms provide simple tools to measure equal legs or to clone a measured move. Fibonacci tools can mark 100 percent projections, since 100 percent represents equality with the prior leg. Such tools are aids, not proofs. The goal is a repeatable framework that keeps attention on the information price is revealing.

Practical Examples in Context

Example 1: Equal Legs in an Uptrend (Daily Bars)

Consider a stock that rallies from 50.00 to 56.00 over 10 daily bars. The first leg measures 6.00 points, or 12 percent. After a 3-bar pause that retraces 2 points, price resumes upward movement. An analyst who tracks symmetry might project a second leg of approximately 6 points above the low of the pause. If the pause low is 54.00, an equal-leg projection would reach near 60.00.

Several outcomes are informative. If price accelerates and reaches 60.20 before consolidating, the second leg slightly exceeds the prior leg. If price hesitates near 59.80 and rotates lower, the second leg nearly matches the first. If the market stalls at 58.50, the second leg proves shorter. Each variant informs how momentum evolved between legs. The precise number is less important than observing whether the market preserved similarity or transitioned to a new rhythm.

Example 2: Percentage Symmetry in a Long-Term Trend

Imagine an index that climbs from 2,000 to 2,400 over several months, then corrects to 2,280. The initial advance was 20 percent. A subsequent sustained advance might be compared on a percentage basis rather than in points, since levels are changing substantially over time. If the next rally begins at 2,280, a move of 20 percent would point to 2,736. Whether the market reaches that level or not, the comparison frames an expectation drawn from observed history rather than personal bias.

Example 3: Time Symmetry in Consolidations

Assume a commodity future rises, then forms a sideways consolidation lasting 12 sessions with contained volatility. After breaking higher, it later pauses again. If the second consolidation also lasts around 10 to 14 sessions, the market is repeating its rhythm in time. If the second pause ends after only 5 sessions, time symmetry has shortened, which can indicate a quicker decision cycle or a change in participation relative to the earlier phase.

Example 4: Range Rotations and Midline Symmetry

Consider a currency pair oscillating between 1.1800 and 1.2000. The full range width is 200 pips, and the midline sits near 1.1900. Price rotates from the lower boundary to the upper boundary, then later drops from the upper boundary back to the lower boundary. These traverses are roughly equal. Analysts may also note half-rotations of about 100 pips from the midline to either boundary. Recognizing this structure helps describe activity as balanced or imbalanced without inferring what should happen next.

Example 5: Pattern Symmetry in a Head and Shoulders

A stock forms a left shoulder where the swing peaks 3 points above a defined neckline and lasts 8 sessions. The subsequent head reaches 5 points above the neckline and lasts 12 sessions. Later, the right shoulder rises 2.8 to 3.2 points above the neckline and lasts 7 to 9 sessions. The shoulders display approximate magnitude and time symmetry with each other, while the head breaks that symmetry. The pattern itself is not the focus here. The observation is that balanced shoulders provide a consistent frame for comparing related swings.

Interpreting Deviations from Symmetry

Symmetry rarely aligns perfectly. Deviations can be as informative as matches. Several interpretations are common in price action work:

- Shorter second leg: A subsequent leg that fails to match the first may suggest waning momentum or earlier profit-taking. Context determines whether the change is meaningful.

- Longer second leg: A leg that materially exceeds the prior distance can signal a shift in urgency, increased participation, or a change in volatility regime.

- Time compression: If a comparable move occurs in fewer bars, the slope increases. That shift can reflect stronger interest or thinner liquidity.

- Time expansion: If the same distance requires more bars, the slope decreases, which can reflect patience, indecision, or opposition near the path.

The meaning of any deviation depends on where it occurs in the larger structure. A shortened leg after a mature trend reads differently from the same shortening early in a new leg. Symmetry should be cross-checked with swing structure, key highs and lows, and the presence of gaps or news events that interrupt otherwise steady behavior.

Methodological Choices That Affect Symmetry

Several technical choices influence symmetry readings. Awareness of these choices helps prevent false precision.

- Linear vs. logarithmic scale: On long-term equity charts, log scaling preserves percentage relationships. Equal percentage moves occupy equal vertical distances on a log chart, while equal point moves do so on a linear chart.

- Bar choice: Daily bars versus intraday bars can change the measured duration of swings. Volume-adjusted bars alter time comparisons further by normalizing for activity rather than clock time.

- Pivot definition: How swing highs and lows are chosen matters. Small pivots produce many symmetric fragments, while large pivots emphasize broader legs. Consistency is essential.

- Instruments and volatility regimes: Futures, currencies, and equities carry different volatility dynamics. A symmetric template that fits one regime may require adjustment in another.

Common Pitfalls

Symmetry analysis can mislead if applied without discipline. Several pitfalls recur:

- Overfitting: With many possible anchors, lengths, and time windows, it is easy to find symmetry that exists only by chance. Predefine comparison rules to reduce this risk.

- Ignoring regime change: Earnings seasons, macro announcements, or central bank actions can alter volatility. Symmetry observed in a calm period may not hold during a shock.

- Scale confusion: Mixing point-based and percentage-based comparisons on the same instrument can produce inconsistent conclusions.

- Selective sampling: Focusing on matches while excluding mismatches creates confirmation bias. Record both to maintain objectivity.

- Assuming causality: Symmetry is descriptive. It does not force price to behave a certain way.

Symmetry Within Broader Price Action Structure

Symmetry gains meaning when situated inside larger patterns of trend and consolidation. Repeated pullback depths have different implications in an early trend leg compared with late-stage action after extended movement. Similarly, a range that continues to deliver equal traverses suggests balance, while asymmetry within the range can warn that balance is changing. Analysts often pair symmetry with higher highs and higher lows, lower highs and lower lows, and key reference lines such as channels or midlines to create a coherent narrative of structure.

Parallel channels naturally emphasize symmetry. A rising channel implies buyers and sellers have negotiated a corridor where higher highs and higher lows align with similar spacing. When price adheres to the channel, the distance between consecutive swing highs or lows often matches with reasonable tolerance. Breaks from the channel indicate a disruption to the previously symmetric process, drawing attention to whether a new structure is forming.

Tools That Assist Symmetry Assessment

Basic chart tools are sufficient. A simple measuring tool can capture leg length in points. A Fibonacci extension or projection can mark 100 percent of the prior leg to visualize equal distances. Parallel lines can clone the slope of a prior move to test whether the market is maintaining its angle. Time markers can flag equal durations between phases. These aids keep the analysis specific and repeatable, even when the market refuses to fit neatly.

Documenting Symmetry for Consistency

Analysts who use symmetry often record their comparisons. A straightforward log might note the reference leg, its size and duration, the projected equivalence, and the actual outcome. Recording both matches and deviations helps build a personal understanding of how closely a given market tends to respect equal legs or repeated durations. The resulting dataset supports more grounded interpretation in the future.

Advanced Considerations

Practitioners sometimes extend symmetry beyond simple equal legs.

- Proportional relationships: Moves that repeatedly align near fractions such as one-half or two-thirds of prior legs can be informative. These are not rules, but recurring ratios can characterize how a market breathes.

- Complex corrections: In multi-leg corrections, internal components can display symmetry even if the entire correction does not. Equal sublegs inside a larger countertrend move are one example.

- Multi-timeframe echoes: A daily equal-leg move can occur inside a weekly measured move. Observing whether symmetry agrees across timeframes can strengthen or weaken interpretations of structure.

- Midpoint and mirror symmetry: Some analysts plot a midpoint of a large swing and observe reflection around it. Balance around the midpoint, or repeated distance above and below it, can mark a subtle form of symmetry.

Limitations and Real-World Friction

Real markets are noisy. Gaps, halts, and external events disrupt the clean geometry that textbooks imply. Liquidity varies across sessions. Overnight risk introduces discontinuities that distort point-based measures, especially in instruments with limited trading hours. The result is a constant tension between the simplicity of equal-leg comparisons and the complexity of live data.

Another limitation is the persistence of evolving participants. Algorithmic activity can compress time between swings, alter intraday microstructure, or target previously obvious reference distances. What looked symmetric for years can change as technology or regulation shifts. An adaptable approach acknowledges that symmetry is a lens, not a law.

Putting Symmetry in Practical Context

Seeing symmetry is only useful if it clarifies the structure. Analysts may ask a few practical questions while reviewing charts:

- Do recent pullbacks share a common depth, or are they expanding or contracting.

- Are the current legs in a trend similar to the early legs, or has the rhythm changed.

- Is a range still rotating with consistent amplitude, or is one side starting to shorten.

- Has the time between swings compressed or expanded compared with the prior phase.

These questions stay within descriptive analysis. They also focus on the market’s behavior rather than personal opinions about value or catalysts. When symmetry aligns with broader structure, the chart usually communicates more clearly.

Extended Example: Building a Symmetry Map

Suppose an equity index shows the following sequence on daily bars:

- Leg A: 4,000 to 4,180 over 12 sessions (4.5 percent).

- Pullback B: 4,180 to 4,120 over 6 sessions (1.4 percent).

- Leg C: 4,120 to 4,300 over 11 sessions (4.4 percent).

- Pullback D: 4,300 to 4,245 over 5 sessions (1.3 percent).

Magnitudes of A and C are nearly equal in percentage terms. Durations are similar as well. Pullbacks B and D also show comparable depth and time. From this history, an observer might note that the market has been advancing in legs of about 4.4 to 4.5 percent, separated by pauses of roughly 1.3 to 1.4 percent. If a new pullback appears, a descriptive framework would ask whether it fits the prior 1.3 to 1.4 percent rhythm or diverges materially. If the next pullback reaches 2.5 percent, the symmetry of the pauses has expanded. If it lasts 10 sessions rather than 5 or 6, time symmetry has changed, even if depth remains similar. These observations refine the reading of market structure without demanding a forecast.

How Close Is “Close Enough”

Very few legs will match exactly. The practical question is tolerance. Some analysts consider a range of plus or minus 5 to 15 percent of the reference size as functionally symmetric, depending on the instrument and timeframe. In quiet conditions, tighter tolerances may be appropriate. In volatile phases, looser allowances avoid labeling normal fluctuation as structural change. Whatever the tolerance, setting it in advance promotes consistency and reduces the temptation to redefine a match after the fact.

Symmetry and Volatility

Symmetry interacts naturally with volatility. When volatility expands, legs tend to lengthen and consolidations often become choppier. The same structure that looked symmetric at low volatility can produce overshoots at higher volatility. Tracking realized volatility in parallel with symmetry observations helps distinguish between a new directional impulse and a volatility-driven enlargement of typical swings. Large changes in volatility can also invalidate comparisons across eras, which is another reason to log observations over time rather than relying on memory.

Ethos of Using Symmetry

Price symmetry thrives as a humble approach. It is a way to listen to the chart. Instead of guessing what should happen, the analyst measures what has happened and asks whether the present still resembles the past. If the resemblance holds, the narrative of structure remains intact. If it breaks, the narrative changes. That ethos supports disciplined interpretation even when markets move in surprising ways.

Key Takeaways

- Price symmetry is a descriptive lens that compares swings in size, duration, slope, or shape to bring order to price action.

- Symmetry appears in equal legs, repeated pullback depths, balanced ranges, and left-right echoes within classical patterns.

- Measurement choices such as point versus percentage scale, pivot selection, and timeframe materially affect symmetry readings.

- Deviations from symmetry are informative and often signal changes in momentum, participation, or volatility regime.

- Symmetry aids interpretation and scenario framing but does not predict or recommend specific trades.