Price action analysis focuses on the information contained in the sequence of prices plotted as bars, candles, or lines. Pure price action puts that visual record at the center of interpretation and intentionally minimizes, or fully excludes, indicators, volume studies, fundamentals, and news. The appeal is clear. Price distills the market’s collective decisions into one observable output. The limitation is equally clear. By design, price-only reading omits context that may be essential for interpreting what those decisions mean.

This article clarifies the concept of the limitations of pure price action, shows how those limitations appear on charts, and explains why understanding them improves the quality of interpretation. The focus is educational. No strategies or recommendations are provided.

Defining the Limitations of Pure Price Action

Pure price action refers to chart interpretation that relies on the shape, sequence, and location of price bars or candles without explicit reference to auxiliary tools. Common elements include swing highs and lows, trend lines, ranges, breakouts, pullbacks, momentum visible in candle bodies, and reversal features such as pin bars or engulfing formations. The method rests on the premise that price alone captures the balance of supply and demand.

Limitations of pure price action are the systematic ways that price-only reading can mislead, remain silent, or become ambiguous. A limitation is not a flaw in the data. It is a boundary on what the data can reveal unaided. These boundaries arise from statistical properties of markets, microstructure frictions, time aggregation, event risk, and the interpretive choices imposed by the chartist.

How Limitations Appear on Charts

Nonstationary behavior and regime shifts

Financial time series are not stable over long horizons. Volatility, liquidity, and the speed of information diffusion change over time. A pattern that appears distinct under one volatility regime may lose meaning when volatility doubles. On a chart, this shows up as patterns that work for months and then degrade rapidly. The bars look similar, but the distribution of outcomes attached to those bars has changed. Price alone does not label the regime change as it occurs.

Microstructure noise and thin liquidity

Short-term charts compress a noisy order flow into candles. When liquidity is thin, small orders can produce long wicks, erratic alternation of colors, and sudden flicks through obvious levels. The visual signature on the chart resembles indecision or rejection even when it is a byproduct of sparse depth rather than a change in aggregate belief. Pre-market and after-hours sessions often display this pattern, as do small-cap equities or off-peak hours in futures.

Timeframe conflicts

Trends and ranges coexist across scales. A strong sequence of higher highs and higher lows on a five-minute chart can sit inside a weekly downtrend. What looks like a breakout on the intraday view may be a routine retest of resistance on the daily view. The chart does not resolve the conflict. The same candle can be part of a continuation on one timeframe and a potential reversal on another. Pure price action offers no rule for selecting which frame dominates.

Gap risk and discontinuity

Gaps introduce jumps that erase or invalidate several bars of incremental price information. A tight consolidation, visually suggestive of compression and potential expansion, can be bypassed in one open through a news-driven gap. The candles before the gap do not predict its direction or magnitude. Price action can show compression, but it cannot infer the catalyst or the sign of the jump.

Subjectivity in drawing structures

Trend lines, channels, and support or resistance zones require discretionary placement. Small changes in anchor points or tolerance for outliers will alter whether a line is respected or broken. Two experienced chart readers can draw different boundaries on the same series. This subjectivity produces ex post clarity when a line happens to fit the subsequent bars and confusion when it does not. The limitation is the degrees of freedom in drawing, not the idea of structure itself.

Ambiguity in reversal candles

Single- or double-candle formations are sensitive to sampling and volatility. A long lower wick may indicate rejection of lower prices. It may also indicate a thin pocket that was filled before liquidity returned. In fast conditions, an engulfing range can occur frequently without implying a durable shift in control. The same candle does not carry the same information in quiet versus turbulent environments.

Volatility clustering and scale effects

Markets exhibit volatility clustering. Quiet days group together, and so do turbulent days. Pure price action identifies clustering only indirectly through candle size. Without a volatility scale, the analyst can mistake an average bar during a high-volatility week for a high-conviction move. Scale choices also matter. Linear and logarithmic axes preserve different relationships. A steep linear slope in a high-priced instrument may represent a modest percentage change. Price-only reading can conflate steepness with economic significance.

Event-driven candles

Earnings releases, regulatory decisions, and macroeconomic prints create candles with unusual ranges, gaps, and reversals. The shape is not only a function of typical order flow but also of scheduled or unscheduled information. Pure price action reveals the result, not the cause. On a chart, this appears as sudden expansions from compression, outsized tails, and follow-through that differs from average behavior on non-event days.

Composite instruments and session boundaries

Indices, exchange-traded funds, and futures represent baskets or contracts with specific trading hours and roll conventions. Session gaps and roll adjustments can create patterns that look like rejections or breaks. The appearance of continuity or discontinuity depends on the data vendor’s session settings and adjustment rules. Price action alone does not advertise those conventions.

Why These Limitations Matter for Interpretation

Recognizing the limitations does not invalidate price action. It clarifies what conclusions are supportable from price alone and where interpretive risk increases. Several reasons are central.

- Calibration of confidence. Without awareness of regime shifts, thin liquidity, or timeframe conflict, the reader may ascribe undue certainty to patterns. Knowing the boundaries reduces overconfidence.

- Separation of pattern from mechanism. Price shows outcomes. Mechanisms such as news, liquidity changes, or rebalancing flows are hidden. Interpreting the same shape identically across different mechanisms can be misleading.

- Avoidance of hindsight fit. The temptation to retrospectively draw lines that explain what happened is strong. A clear understanding of subjectivity helps prevent narrative overreach.

- Alignment of horizon. Acknowledging that multiple timeframes can deliver conflicting signals encourages careful selection of the horizon relevant to the question at hand.

- Awareness of statistical uncertainty. Price patterns do not come with built-in base rates. Assuming reliability without evidence risks confusing coincidence for structure.

Practical Chart-Based Contexts and Examples

False breakout in a well-defined range

Consider a daily chart with months of well-visited highs near a round number. One session pierces the range with a tall candle, closing slightly above the boundary. On the next session, price returns inside the range and closes mid-body. The two-day sequence looks similar to a textbook failed breakout. From a price-only perspective, the interpretation is that supply reasserted itself near the high. Yet the same two candles could be explained by a thin overnight session that let price drift beyond the boundary, followed by a normal-volume return to the prior region. The chart does not distinguish a structural rejection from a liquidity artifact. The limitation is not that the candles lack meaning, but that their meaning is not unique.

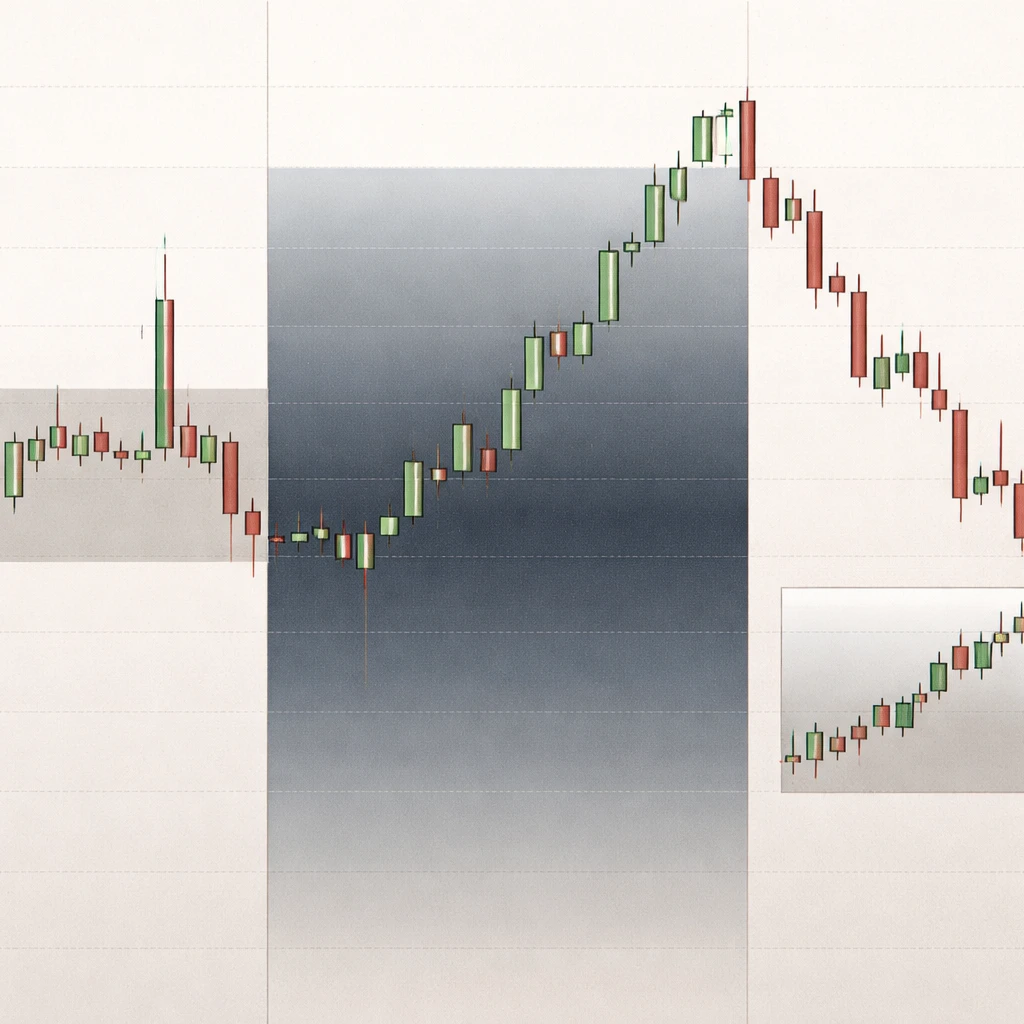

Intraday strength nested in a higher-timeframe downtrend

A five-minute chart shows persistent higher highs and higher lows across the morning, with small pullbacks and strong closes. The daily chart, however, remains in a months-long downtrend with lower swing highs. The intraday sequence might reflect a modest reversion within a larger decline. Depending on which timeframe governs the reader’s horizon, the same intraday strength has different implications. Pure price action does not resolve which frame is primary. The limitation is the dependence of meaning on scale.

Gap through a consolidation cluster

On a daily chart, a tight cluster of candles forms with overlapping bodies and short ranges. The cluster suggests compression. A subsequent open produces a large gap that lands well beyond the cluster, then drifts without returning to the prior day’s range. The pre-gap cluster provided no directional information. The event that produced the gap overwhelmed the local dynamics. Price action described the consolidation, but it could not infer the character of the forthcoming jump. The limitation lies in the inability of local price structure to encode imminent discrete information releases.

Long wicks in thin hours

An hourly futures chart displays several candles with prominent upper and lower shadows around a visible level during the night session. During the primary session, the same level is approached with smaller wicks and heavier trade. The night-session wicks may look like decisive rejections. The day-session behavior reveals that the earlier tails were likely artifacts of sparse depth. The price-only view at night overstated the significance of those wicks.

Sharp trend with repeated small pullbacks

On a strong advance, the chart prints a sequence of small-bodied pullbacks that barely retrace. Reading this as persistent demand is reasonable. A limitation arises when that interpretation is generalized. Similar shapes can occur during short covering, rebalancing flows near month-end, or systematic volatility targeting that reduces selling pressure. The same geometry does not guarantee the same underlying drivers, and therefore not the same persistence.

Compression before a scheduled event

A series of inside bars often signals lower realized volatility. Before a major policy announcement, inside bars can proliferate as participants await the release. The shape is familiar, but the cause is different from compression that stems from the market’s own feedback dynamics. Once the event arrives, price can gap or trend sharply regardless of the immediate pre-event candles. The limitation is that identical visible patterns can precede very different distributions of outcomes.

Log versus linear slope interpretation

A stock that rises from 200 to 210 prints a 10-point move. On a linear chart, the slope looks steep relative to a prior move from 20 to 30, which is also 10 points. On a logarithmic chart, the percentage change is correctly shown as smaller in the first case and larger in the second. A price-only read on a linear axis can unintentionally conflate point moves with percentage moves, altering perceived momentum and the meaning of slope.

Data and Visualization Choices That Shape Price-Only Reading

Price bars are aggregates. How they are constructed matters. Several technical choices change what the chart shows and thus what pure price action can say.

- Session definitions. Including or excluding after-hours alters gaps and wicks. An instrument that trades around the clock will look different when only regular hours are shown.

- Corporate actions and adjustments. Splits, dividends, and index reconstitutions can produce discontinuities. Different adjustment conventions will either smooth or preserve jumps.

- Data vendor differences. Tick filtering, outlier handling, and time-stamp alignment vary. Small discrepancies can shift the exact level of a swing high or low.

- Bar construction. Time bars, volume bars, and range bars segment the same series differently. Price-only reading of one representation should not be assumed to transfer unaltered to another.

- Instrument specifics. Futures rolls and contract specifications produce characteristic gaps or plateaus. An unadjusted continuous series may show apparent breaks that are mechanical rather than economic.

A Statistical View of Pattern Reliability

Price action patterns are hypotheses about conditional tendencies. Do ranges break to one side more often than the other under certain contexts. Do long lower wicks cluster near durable lows. These are empirical questions. The limitation of pure price action is not that such hypotheses are wrong. It is that the chart alone provides no base rates nor an indication of how performance changes across regimes.

Two statistical issues are central.

- Multiple testing and selection bias. A chartist inspects many shapes across assets and horizons. The human eye highlights patterns that look meaningful. Without careful out-of-sample testing, many highlighted examples are selections that fit noise in hindsight. The more degrees of freedom in drawing lines and choosing windows, the higher the risk of overfitting.

- Distribution shift. Even if a pattern had empirical support in a prior interval, market structure evolves. Transaction costs, liquidity provision, and participation mix change. The mapping from pattern to outcome can drift. Pure price action offers no built-in mechanism for detecting that drift.

These issues do not prohibit the use of price action. They imply that interpretation should be conditional, probabilistic, and modest in scope when based on price alone.

Behavioral and Cognitive Sources of Misinterpretation

Price-only charts invite extrapolation and narrative building. Several well-documented cognitive tendencies can interact with the method.

- Hindsight and outcome bias. After a move, prior candles are reinterpreted as precursors. The narrative feels coherent because the outcome is known.

- Confirmation bias. Once a pattern is suspected, the eye overweights subsequent candles that align with it and underweights contradictory evidence.

- Anchoring on visible levels. Round numbers and prior peaks attract attention. This is reasonable, but it can produce false precision regarding how important a level is to the broader market.

- Recency bias. Fresh moves are salient. The last few bars receive outsized weight even when the relevant horizon is longer.

Awareness of these tendencies helps prevent overconfident readings based solely on geometric features of recent candles.

How Understanding the Limitations Helps Interpretation

Recognizing the boundaries of price-only information improves interpretive discipline. Several benefits are practical for chart reading.

- Context sensitivity. The same shape has different meaning when volatility is high, when liquidity is thin, or when scheduled events are imminent. A disciplined reader asks what non-price context could explain the shape, then treats conclusions as provisional.

- Horizon clarity. Before drawing implications from a formation, the reader clarifies the relevant timeframe. Conflicting signals across frames are expected, not paradoxical.

- Respect for discontinuities. Gaps and jumps are part of price dynamics. Candles leading into a jump need not foreshadow it. Interpreting pre-jump structure with humility prevents overreading.

- Attention to construction. Knowledge of the data’s session, adjustment, and bar construction prevents misinterpretation of mechanical artifacts as market intent.

- Probabilistic language. Price action is more informative when phrased as tendencies rather than certainties. This aligns interpretation with the uncertainty inherent in markets.

Additional Chart Illustrations of Limitations

Overlapping candles within a broadening formation

A series of higher highs and lower lows can create a broadening shape. Within it, many candles overlap and reverse quickly. The formation looks dramatic, yet the overlapping nature means local follow-through is inconsistent. Pure price action might suggest expanding volatility, which is correct descriptively, but it says little about direction. The limitation is the instability of implications when price swings widen without a directional anchor.

Support and resistance drawn post hoc

After price reverses near a level, it is tempting to draw a horizontal line and treat the reversal as evidence of a pre-existing zone. If the level had not been marked in advance, the inference is at risk of hindsight labeling. Many price paths will cross many candidate levels. Some reversals will align with a level by chance. The chart itself does not label which lines mattered ex ante.

Persistent drift with low realized volatility

Slow grinding moves with small daily ranges can cover substantial distance. Price-only reading can underweight these moves because no single candle is striking. The reverse also occurs. A few very large candles can overstate the sense of trend strength when, in percentage terms, the move is modest and quickly mean reverting. The limitation is the human tendency to infer meaning from visual salience.

Questions That Help Bound Interpretation

The following questions structure a cautious reading of price-only charts without prescribing strategies.

- What is the relevant timeframe for the question being asked, and what do adjacent timeframes imply that might conflict with it.

- How has volatility changed relative to recent history, and does candle size reflect that change.

- Are session settings, adjustments, and roll conventions introducing gaps or plateaus that look like signals.

- Is the market near a scheduled event that could dominate local formations.

- Could thin-liquidity periods be producing exaggerated wicks or temporary breaks.

- How many discretionary choices were made in drawing levels or lines, and could small changes alter the conclusion.

- Is the observed pattern rare or common in the recent sample, and what base rate would be required to view it as informative.

Role of Complementary Information

Many practitioners use price action as a core descriptive framework while consulting other information such as volume, volatility measures, or fundamental catalysts. This is not a prescription. It illustrates that the limitations described above are widely recognized. Price is necessary and powerful, but it is not self-sufficient for many interpretive tasks. Knowing what it does not say is as important as reading what it does say.

Concluding Perspective

Pure price action offers an elegant, direct view of market behavior. Its strengths are descriptive clarity and universality across assets and horizons. Its limitations stem from the same sources that make markets complex. Time variation, liquidity conditions, discontinuities, subjective drawing, and the absence of base rates restrict how much can be inferred from shapes on a chart. Recognizing these constraints refines interpretation. It shifts the reader from categorical judgments to measured assessments that respect uncertainty and context.

Key Takeaways

- Pure price action is informative but incomplete. It omits context that can change the meaning of identical shapes.

- Chart features that look decisive can arise from thin liquidity, session settings, or data construction rather than broad participation.

- Conflicting messages across timeframes are normal. Price-only reading does not privilege one horizon over another.

- Gaps and regime shifts limit the predictive value of local formations. Candles describe outcomes without revealing causes.

- Sound interpretation treats patterns as probabilistic tendencies and remains aware of selection bias and distribution shift.