Price action is the study of market behavior through price itself. It relies on the sequence of highs, lows, opens, and closes, and the shapes that emerge from these sequences. Because the approach often uses minimal indicators, interpretations can be deceptively simple. This creates fertile ground for misconceptions that appear convincing on a chart but lack reliability when context changes. Understanding these misconceptions is essential for reading charts with discipline and for avoiding overconfident narratives that do not match how markets actually move.

What Counts as a Price Action Misconception

A price action misconception is a belief about how price behaves or what a visual pattern implies that does not hold consistently across markets, timeframes, or regimes. Misconceptions are not merely wrong ideas. They are often partially true in narrow conditions, which makes them persuasive and persistent. They can arise from selective memories, publication bias in examples, overfitting to a small sample, or the human tendency to see structure in noise.

In charts, misconceptions typically show up as rigid rules applied to flexible situations. A common example is treating a single candle as decisive evidence without considering what came before, what market participants are likely doing now, or how volatility and liquidity influence the same candle shape at different times of day.

Why Traders Pay Attention to Misconceptions

Misconceptions matter because chart reading is an exercise in inference under uncertainty. Price action is not a set of laws. It is an interpretive framework guided by probabilities that shift with context. Misunderstandings about candles, levels, or breakouts lead to misplaced confidence and to misinterpretation of risk. Clarifying what a chart can and cannot say improves communication, record keeping, and consistency in analysis, even if it does not guarantee accurate forecasts.

Better interpretation also supports more coherent post-trade or post-analysis reviews. When conclusions are grounded in context rather than myths, it is easier to diagnose whether a decision was reasonable regardless of outcome.

How Misconceptions Appear on Charts

On charts, misconceptions tend to appear as overemphasis on discrete, visually striking features. Examples include dramatic wicks, a level drawn as a razor-thin line, or a breakout bar that closes at a high extreme. Without context, such features are often explained with certainty. With context, they are one piece in a much larger picture that includes volatility regime, session timing, liquidity conditions, and the higher timeframe structure.

Candlestick clusters, ranges, and trend legs can look similar while representing very different participation. A tight range during an earnings blackout period is not the same as a tight range during an options expiration week. A clean drive through a level during the European session in a currency pair is not the same as a drive during the lower liquidity of a late U.S. afternoon. The candle shapes can be similar, yet the underlying conditions differ in ways that affect interpretation.

Common Misconceptions and What the Chart Actually Shows

1. A single candle tells the full story

Large bodied candles, long wicks, or textbook dojis often attract strong interpretations. In practice, a single candle is an incomplete sample. A long lower wick can indicate aggressive buying into a dip, or it can be the result of a stop run in a thin moment that quickly mean reverts, or it can be routine noise within a higher volatility regime where larger tails are normal. The effect of time of day is critical. A long wick printed at the open in a stock index future after an overnight news release does not carry the same weight as a long wick printed in a quiet midday period.

Charts provide sequences, not isolated pictures. The candle that seems meaningful is better read relative to its neighbors, its location within a swing, and the prevailing range of true price movement.

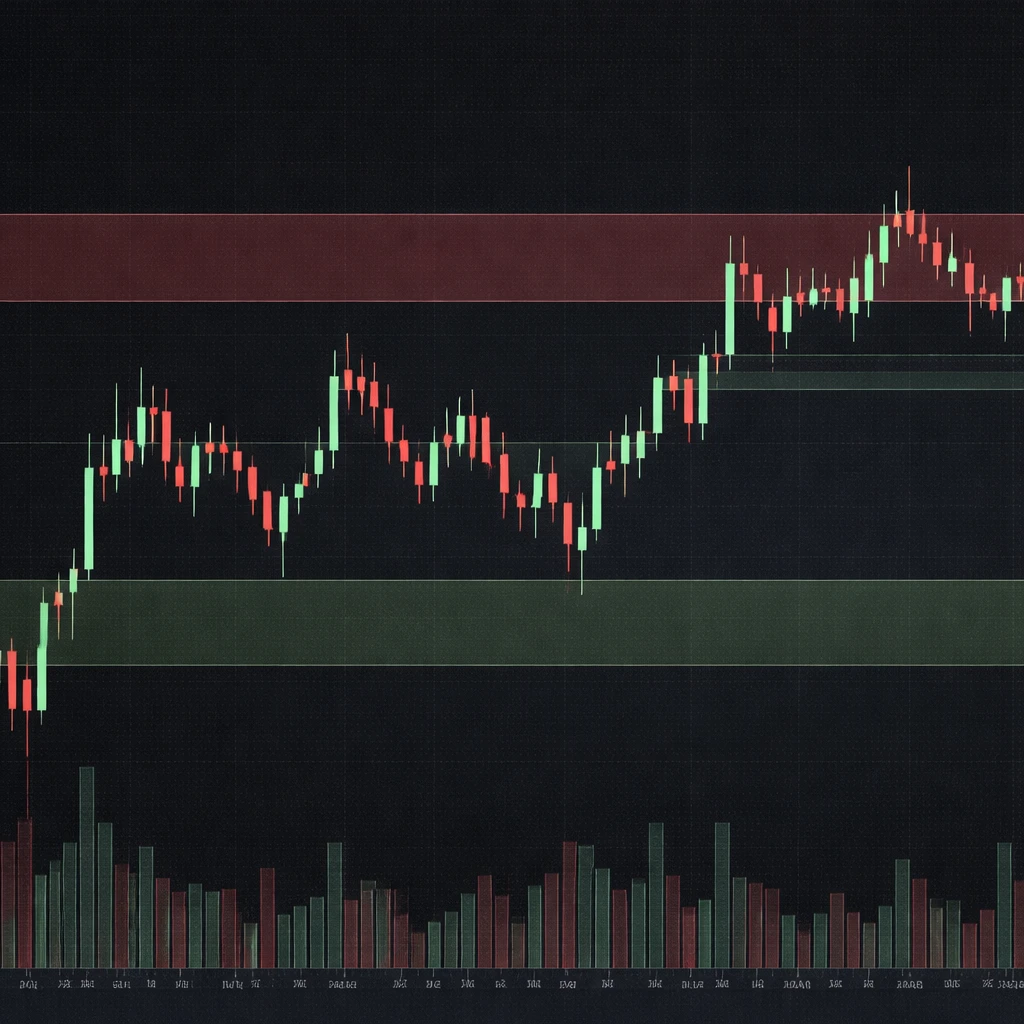

2. Support and resistance are exact lines

Support and resistance are better treated as zones rather than single price levels. Limit orders do not sit precisely on one tick. Liquidity tends to cluster within ranges that reflect prior balance, option hedging bands, or round-number preferences. On a chart, a level that appears to hold to the tick may be an illusion created by chart granularity or by a fortunate coincidence in that sample.

Visually, this misconception shows up as repeated tapping of a line without recognizing that the true area of interest spans several ticks or cents. Many apparent breakthroughs are simply visits to the far edge of the zone. Slight overshoots are common and do not inherently change the character of the market.

3. Breakouts must follow through immediately

A breakout is a move beyond a prior boundary, usually accompanied by an expansion in range. The misconception is that any breach of a boundary has to continue in the same direction or it is a failure. Real breakouts often display back-and-fill behavior, partial acceptance beyond the level, or a pause as resting orders are absorbed. Other times, a breakout is simply a temporary displacement that returns into the prior range, sometimes swiftly.

On the chart, these situations can look very similar at first. An hourly candle can close beyond a boundary with strength in both cases. Differentiating them requires more than the candle close. The tone of subsequent bars, the presence or absence of rising participation, and the placement of the move within a wider structure matter.

4. Gaps always fill

Gaps are areas where no trading occurs between one bar’s close and the next bar’s open for that instrument and session. The belief that gaps must fill is common in equities because many gaps do eventually trade back. Yet this is not a law. Some gaps persist for months or years. The fill rate depends on capitalization, sector, catalyst, and the timeframe used to define a gap.

On charts, the misconception appears as automatic expectation of a return into the prior range. Properly read, a gap is a statement about a sudden repricing. Whether that repricing is accepted, rejected, or partially digested varies with news flow, liquidity, and the presence of strong counterparties.

5. Long wicks always mean rejection

Long wicks are often described as rejection. Sometimes that description is valid. Other times, the wick is simply the tail end of a one-sided auction that exhausted into resting liquidity. In fast conditions, the wick can be widened by spreads and slippage. In futures or crypto outside peak hours, a single large order can create a wick that does not reflect broad participation.

On a chart, a wick gains meaning from the effort that followed. If a long upper wick forms and price then compresses and holds just beneath it, the wick may be less meaningful than the subsequent acceptance in that area. The wick alone is not enough evidence.

6. Trendlines are objective and precise

Trendlines depend on which swing points a reader selects, whether the chart uses linear or logarithmic scaling, and the timeframe displayed. Two competent analysts can draw different yet defensible lines. Treating trendlines as objective tools leads to misplaced confidence in exact touches or breaks.

On the chart, this shows up as overreliance on angle and precision. A more grounded view treats trendlines as visual guides that mark slope and tempo rather than as hardened boundaries. Small breaches or near misses are common and should not be overinterpreted.

7. Patterns mean the same thing across timeframes

Price action is often described as fractal. While certain structures recur, the quality of a pattern changes with timeframe. Lower timeframes include more microstructure noise, more influence from order execution details, and larger proportional transaction costs. A one-minute engulfing bar is not equivalent to a daily engulfing bar. The apparent similarity can mask very different underlying conditions.

On charts, the misconception appears when a short-term pattern is given the same interpretive weight as a higher timeframe pattern without reconciling the two. Conflicts between timeframes are usual, not exceptional.

8. Price action excludes volume or other context

Some readers insist that price alone is sufficient. Price carries much information, but the interpretation of price behavior often benefits from context. Volume, time of day, scheduled events, and even options positioning can influence the reliability of a pattern. For instance, a breakout on very low volume late in the session may carry less informational value than a breakout with building participation near an active open.

On a chart, absence of context can lead to misreading normal noise as meaningful motion. Price action is compatible with context, even when the chart itself remains relatively uncluttered.

9. Named candlestick patterns guarantee outcomes

Pattern names like engulfing, hammer, shooting star, inside bar, or outside bar are memory aids. They are not guarantees. The same pattern printed in consolidation after a large move can lead to continuation, while the same pattern printed into an old area of friction may stall. The average outcome of such patterns across markets tends to be modest without strong contextual filters.

On charts, the misconception appears when the pattern name substitutes for analysis. The name describes shape, not motive force.

10. The close is the same across markets

In equities, the official close carries significance. In currencies and crypto, there is no centralized close. Platform-specific or broker-specific closing times can create artificial signals. A bar that appears to close decisively on a platform may not align with another venue. Treating all closes as equally meaningful conflates different market structures.

On charts, this appears as overemphasis on bar closes in instruments that trade nearly around the clock. Session boundaries and liquidity cycles are more informative in these cases than any arbitrary daily close.

11. Backfitting patterns equals evidence

After seeing a move, it is easy to point at a precursor and label it. Human memory preserves impressive examples and forgets the dull or contradictory ones. The chart then becomes a slide deck of greatest hits rather than a balanced record. Without careful sampling, a pattern can appear highly reliable when it is not.

On charts, backfitting often appears as a tidy sequence of annotated patterns that missed the many instances where similar shapes led to routine noise. A robust view requires counting both. Without controlled sampling, the visual conviction that a shape works is misleading.

12. Ranges are random and trends are orderly

Ranges are often treated as aimless. Trends are often treated as structured and clean. In reality, ranges have internal organization that can be read, and trends are frequently interrupted by deep pullbacks, variations in slope, and pauses with little overlap that then reverse sharply. Overidealized views of both regimes lead to surprise when the market behaves in normal yet untidy ways.

On charts, the misconception shows up as frustration with choppy conditions and overconfidence in smooth legs. Accepting typical range behavior and typical trend variability helps align expectations with what charts actually deliver.

13. More touches strengthen a level unequivocally

Repeated touches of a zone can indicate that a market respects that area. They can also indicate that resting orders are being consumed and that the path through the level is easier with each test. Both interpretations are plausible. Which one dominates depends on how price behaves during and after the touches, the speed of approaches, and whether participation is thinning or increasing.

On charts, the misconception shows up as unwavering confidence with each touch. A more balanced view asks whether the market is expending or accumulating effort near the zone.

14. Equal highs and equal lows are strong barriers

Equal extremes can mark visual symmetry that many viewers notice. That very visibility can attract protective orders, which become targets. The area can act as a magnet rather than a wall. A print above equal highs followed by a return into the prior range is common and does not necessarily indicate a major reversal. It may reflect routine harvesting of liquidity.

On charts, equal extremes that are repeatedly approached deserve context rather than an automatic label of strength.

Practical Chart Contexts and Examples

Example 1: An index future with an opening gap

Consider a U.S. equity index future that opens with a noticeable gap up after a macro headline. The first five-minute candle is large and closes near its high. The gap area from the prior settlement to the current open appears as a vacuum. A frequent misconception is that the gap must fill quickly because it is open space on the chart. Equally common is the belief that the strong first candle ensures continuation.

What the chart actually provides is an observation that price has repriced. Whether this repricing is accepted typically becomes clearer over the next sequence of bars. If volatility is elevated and volume is distributed broadly across the session, partial fill and back-and-fill behavior are not unusual. If participation is concentrated in the opening rotation, a short-lived drive followed by balancing is also common. The gap itself is not a directive. It is a contextual feature that interacts with the day’s liquidity and event calendar.

Example 2: A currency pair near a weekly level

Suppose EURUSD approaches a weekly area where price previously turned. On an hourly chart, multiple candles show upper wicks that briefly press through the zone. A strict reading of each wick as rejection suggests persistent selling. Another interpretation is that buy stops above prior highs are being harvested while the market remains undecided. If the pair trades during overlapping London and New York hours, the same wick may carry more information than a wick formed in the quiet Asian session.

The chart shows that wick frequency alone does not settle the question. The sequence after each wick, the breadth of participation, and the time of day help differentiate typical auction behavior from decisive rejection.

Example 3: A single stock after earnings

A large capitalization stock reports earnings, gaps higher, and posts a wide-range first hour. The daily chart later prints an apparent outside day. The misconception is to treat the outside day as a predetermined signal. Earnings change the information set. Post-earnings flows include analyst updates, institutional rebalancing, and options hedging shifts. The same candle shape that might imply one thing on a normal day now coexists with non-routine flows. The chart still matters, but its shapes should be read through the lens of changed conditions.

How to Read Price Action Without Falling for Myths

A disciplined reading of price action does not require complex models. It does require consistency and respect for context. The following practices help separate observation from myth. These are not strategies. They are ways to frame what the chart is likely telling you and what it cannot tell you.

- Define the working timeframe and one higher timeframe, then reconcile conflicts rather than averaging them away.

- Mark zones as areas with width, not single lines. Allow for tolerance that reflects typical volatility.

- Note session boundaries, scheduled news, and liquidity cycles. A similar candle can mean different things at different times.

- Track realized volatility with simple measures such as range averages to avoid overinterpreting ordinary fluctuations.

- Record examples that contradict your favored readings to balance the sample you remember.

Interpreting Chart Features in Context

Candles and sequences

A candle’s meaning is downstream of its neighbors. Two large candles in opposing directions in the middle of a wide prior range often signify noise. The same two candles at the edge of a multi-week consolidation carry more information. Treat candles as words in a sentence. The grammar includes placement, tempo, and continuity.

Zones and tolerance

Drawing levels as shaded regions helps reset expectations. Market microstructure is not precise in practice. Slight breaches, spikes, and minor overshoots are part of the process. The willingness of price to accept and build within a zone is often more informative than a single touch.

Breakouts and acceptance

When price leaves a range, observe whether it can build structure beyond it. Consolidation outside the prior range suggests partial acceptance. A quick return suggests displacement without acceptance. Neither outcome is guaranteed, and both are common occurrences in normal markets.

Wicks and effort

Wicks show where price traveled, not necessarily where committed two-sided trade occurred. What happens next is often more revealing. If a long upper wick is followed by overlapping bars that hold near the wick’s base, the market may be absorbing supply rather than rejecting price.

Timeframes and translation

Lower timeframe noise can dramatize or hide the same structural idea visible on a higher timeframe. Translating observations across timeframes is a skill. The smaller chart can supply detail, while the larger chart supplies hierarchy. Conflicts are normal and do not require forced resolution.

Data Quality and Chart Settings That Create Misconceptions

Misconceptions are often reinforced by chart settings. Differences in time zone, session templates, and whether the chart uses premarket or after-hours data can change candle shapes. Logarithmic versus linear scaling alters angle and slope, which can shift trendlines. Heikin Ashi or Renko representations smooth price and can make ranges or trends appear cleaner than they are on standard OHLC bars.

Thinly traded instruments produce spiky candles that invite misreading. Instruments with multiple venues, such as FX, lack a single authoritative close. Cross-checking data feeds and understanding what a bar represents in that market reduces the risk of drawing false conclusions from presentation artifacts.

Behavioral Reasons Misconceptions Persist

Human perception seeks patterns. Salient examples are memorable and are often repeated in educational materials because they are visually striking. Survivorship bias and selection bias then inflate the apparent reliability of a pattern. Narrative coherence is comfortable, so post hoc explanations feel convincing even when they have little predictive content.

On charts, this leads to a high ratio of highlight reels to mundane sequences. Repeating this cycle embeds misconceptions as tacit rules.

What Price Action Can Reliably Offer

Price action offers a disciplined way to observe market behavior with minimal latency and minimal model reliance. It is most reliable when it is used to describe what is happening with clear language about uncertainty and context. It can mark where the market has moved efficiently versus where it has hesitated, where acceptance is building versus where price is being tested. It can organize attention around zones that matter for many participants. It cannot promise that a given shape produces a given outcome, and it cannot reduce uncertainty to a simple binary.

Putting It Together on the Chart

When you look at a chart with these ideas in mind, you will likely notice several shifts in perspective. Single bars become less decisive. Zones replace lines. Breakouts are seen as a process that includes acceptance or rejection, not as a one-bar verdict. Wicks are pieces of evidence, not conclusions. Equal highs and equal lows are potential liquidity targets, not necessarily permanent barriers. Conflicts across timeframes are acknowledged rather than smoothed out.

These shifts do not eliminate uncertainty. They refine it. Instead of debating whether a textbook pattern is present, the analysis focuses on whether the market is organizing around a theme that persists across bars and across timeframes, and whether the conditions that gave rise to a visual feature are likely to be stable or fleeting.

Key Takeaways

- Common price action misconceptions arise from rigid rules applied to flexible market conditions and from selective examples that overstate pattern reliability.

- Context matters: volatility, session timing, liquidity, and higher timeframe structure change the meaning of the same candle or pattern.

- Support and resistance behave as zones with tolerance, not exact lines, and slight overshoots are common parts of normal auction behavior.

- Breakouts, gaps, wicks, and named patterns are observations, not directives, and gain meaning from what follows and from participation.

- Data settings, market microstructure, and behavioral biases can turn charts into persuasive stories that are not supported by broad evidence.