Overview

Trailing stops are a structured way to exit positions that move unfavorably after reaching higher watermarks. They create a moving threshold that follows price when it advances, then holds steady when price reverses, triggering an exit once a defined giveback has occurred. The technique aims to preserve a portion of open profit while capping losses that develop after a prior gain. It is a rules-based approach that supports consistency, particularly under stress when discretion tends to erode discipline.

In risk management terms, trailing stops shape the distribution of outcomes by limiting the size of adverse excursions after the trade has moved in a favorable direction. This changes the profile of drawdowns at both the position and portfolio level, which is central to capital protection and long-term survivability.

Definition and Core Mechanics

A trailing stop is a dynamic stop level that moves with the market only when the trade is making progress. For a long position, the trailing stop rises as price rises and remains unchanged when price falls. For a short position, the trailing stop declines as price declines and remains unchanged when price rises. The stop triggers when price touches or crosses the trail, converting an open trade into an exit order type specified in advance, usually a stop-market or stop-limit.

Two components define any trailing stop:

- The reference for movement: price extremes, closing prices, moving averages, or a volatility measure such as the Average True Range.

- The offset: a fixed amount, a percentage, or a multiple of volatility that determines how far the trail sits from the reference.

When price makes a new favorable extreme relative to the position, the stop ratchets forward by the same offset. When price retraces by more than the offset, the stop is hit and exits the position. The general idea is straightforward, yet implementation details determine practical effectiveness.

How Trailing Stops Differ from Fixed Stops and Profit Targets

A fixed stop does not move once set. It defines the maximum initial risk and remains in place throughout the trade, even if the position becomes profitable. A profit target exits at a predetermined favorable price level, capturing gains but possibly truncating further upside. A trailing stop attempts to balance these ideas. It limits downside after the trade has advanced by reducing the distance between current price and exit level, yet it allows the position to remain open as long as price continues to improve.

Importantly, trailing stops do not guarantee profit capture. They simply implement a rule for tolerating a specific giveback from the most favorable level observed. If price reverses sharply, particularly through a gap, the executed exit may occur worse than the stop level, depending on order type and market conditions.

Order Types and Execution Effects

The practical behavior of a trailing stop depends on how the exit is routed and triggered:

- Stop-market: when triggered, it sends a market order. It prioritizes execution certainty but can experience slippage during volatile moves or gaps.

- Stop-limit: when triggered, it sends a limit order with a specified price limit. It can reduce slippage but introduces non-execution risk if the market trades through the limit without filling.

- Broker or platform specifics: some platforms maintain trailing logic on the server or client side, and some trail on last trade, bid, or ask. These details affect trigger timing and fill quality, especially in fast markets or illiquid instruments.

Execution quality is not uniform across markets. Stocks that gap on news, thinly traded futures contracts near settlement, or currency pairs around data releases can all produce fills that differ materially from modeled assumptions. Any risk control plan that uses trailing stops benefits from acknowledging these microstructure realities.

Why Trailing Stops Matter for Risk Control

Risk management is about the size and frequency of adverse outcomes. Trailing stops aim to curtail large givebacks after a trade has reached a better state than the entry. By ratcheting the exit level as price improves, trailing stops reduce the potential drawdown from the peak of open equity in that position. This has several risk-control implications:

- Drawdown containment: smaller reversals from peaks reduce the depth and duration of equity curve declines.

- Outcome skew: by letting favorable moves run while cutting reversals after a defined giveback, trailing logic can magnify a minority of larger winners in trend-friendly conditions.

- Process stability: mechanical exits promote consistency during losses or hot streaks, reducing the temptation to override rules based on recent outcomes.

- Capital survivability: capping tail losses after gains accumulate can help keep the portfolio within risk limits that allow continued participation across many trades.

None of these points imply that trailing stops improve every trade. They shape the distribution rather than guarantee a better average outcome. Their utility depends on market behavior, volatility regime, and the trader’s holding period.

Common Ways to Construct a Trailing Stop

There are many valid constructions. Each choice comes with trade-offs between responsiveness and noise tolerance.

- Fixed percentage trail: the stop is set a constant percentage below the highest price achieved since entry for a long position, or above the lowest price for a short. It is simple, platform-agnostic, and easy to communicate. It is also insensitive to changing volatility.

- Fixed currency or tick trail: similar to percentage, but set in units of price or ticks. Often used in futures where tick values are standardized.

- Volatility-based trail: distance set as a multiple of a volatility metric, commonly the Average True Range over a lookback window. This adapts to regime changes. During quiet periods the trail sits closer, and it widens during turbulent periods to avoid whipsaws.

- Indicator-based trail: the stop trails a moving average, a Donchian channel, or a chandelier-style level that references the highest high minus a volatility offset. This embeds a structural view of trend and noise into the exit.

- Time-conditioned trail: the trail updates only at specific intervals, such as end-of-day or after each completed hour, to reduce intraday noise.

None is universally superior. Selection depends on objectives, instrument characteristics, and the sampling frequency that aligns with the rest of the process.

Illustrative Examples

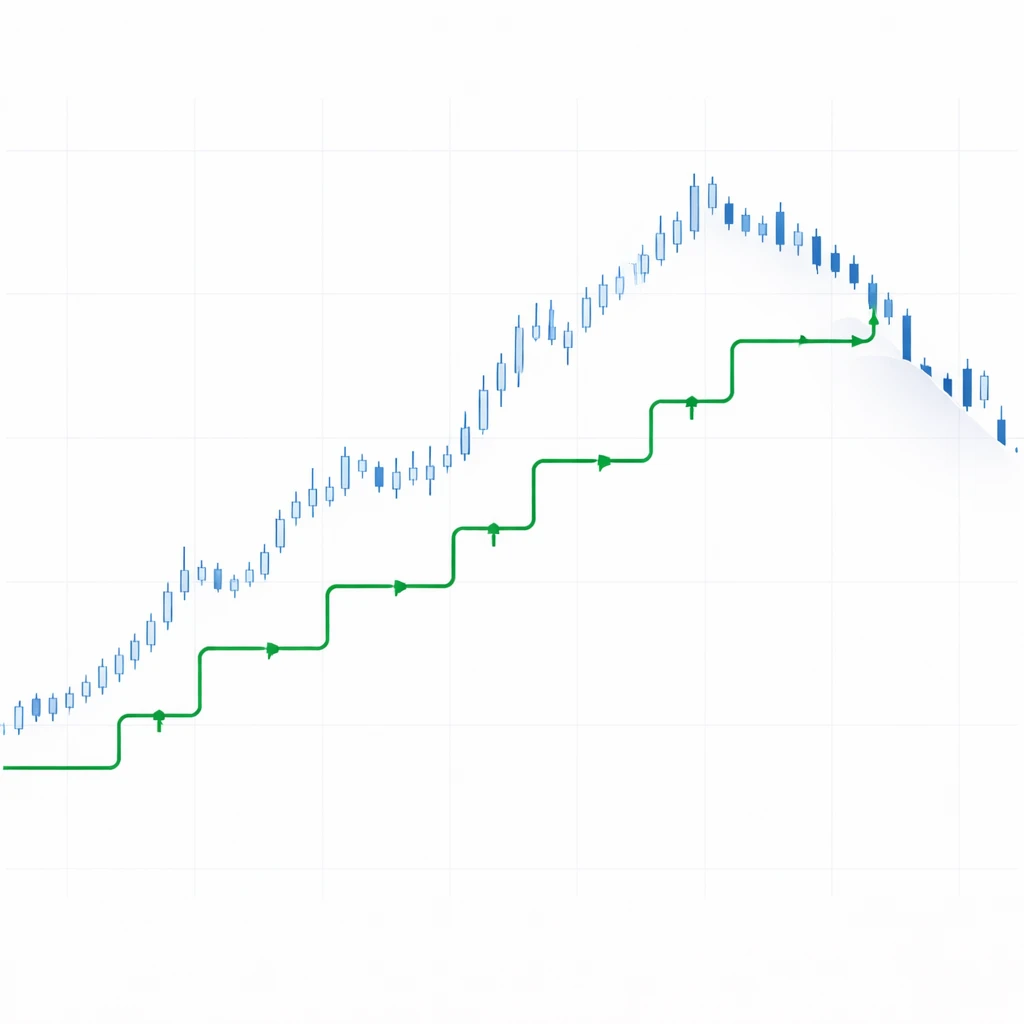

Example 1: Long Position with a Percentage Trail

Assume a long entry at 100 with a 10 percent trailing stop. At initiation, the stop sits at 90. If price rises to 120, the new peak is 120 and the stop ratchets to 108. If price then falls to 108, the stop triggers. The realized result would reflect transaction costs and any slippage from the stop execution method.

Several features are evident. The stop moved only when price set a new high. If price later advances to 130, the stop would rise to 117. If price never makes a new high after 120, the stop remains at 108 until triggered. The exit level protects a portion of the open profit yet still allows the position to continue if the trend resumes.

Example 2: Volatility-Based Trail for a Long Position

Suppose the same long position references a 14-day Average True Range of 2.5 with a distance of 3 times ATR. The trail would initially sit 7.5 points below the highest close or high, depending on the chosen rule. If volatility doubles and ATR rises to 5.0, the trail would widen to 15 points below the peak, allowing more room for price oscillation. If volatility compresses, the trail tightens naturally. This adaptiveness can mitigate the common problem of fixed trails being too tight in volatile environments or too loose in quiet conditions.

Example 3: Short Position with a Fixed Currency Trail

Consider a short entry at 50 with a trailing distance of 2 points. The stop begins at 52. If price drops to 45, the new favorable extreme is 45, so the stop trails to 47. If price then rebounds to 47, the stop is hit. The logic mirrors the long side but in reverse. The stop only moves closer as the trade becomes more profitable, then holds its ground during adverse movement, providing a structured exit.

Key Design Choices and Trade-offs

Design involves balancing sensitivity to trend against resilience to noise. Several choices shape this balance:

- Distance: a wider trail reduces whipsaws but increases giveback. A tighter trail captures profits sooner but risks premature exits during normal pullbacks.

- Reference price: using intraday highs or lows creates more sensitive adjustments than using closing prices. End-of-day updates can reduce noise for swing horizons, while intraday updates suit shorter-term horizons.

- Update frequency: continuous updating can lead to more trades and higher costs. Interval-based updating can smooth execution but may delay necessary exits during rapid reversals.

- Order choice: stop-market favors execution certainty under stress, while stop-limit controls price but risks missing the exit during fast gaps.

- Instrument behavior: assets with frequent gaps or low liquidity create larger slippage risks. Volatility clustering can persist, which favors rules that adapt to changing conditions.

There is no free lunch. A trail that performs well in quietly trending markets may struggle in choppy, mean-reverting ranges. Conversely, a tight trail that performs well in ranges may repeatedly exit before trends mature. The objective is internal coherence with the broader process rather than chasing context-specific perfection.

Operational Pitfalls and Misconceptions

- Guaranteed profit: a trailing stop does not lock in a specific gain. Gaps and thin liquidity can produce fills worse than the stop level.

- Universal superiority: trailing stops are not always better than fixed stops or time-based exits. Their effect depends on how price trends and how noisy the path is.

- One-size-fits-all distances: the same percentage trail applied to different instruments or timeframes can produce very different behavior.

- Ignoring transaction costs: tighter trails can increase turnover and costs, which can erase the perceived benefits observed in simplified backtests.

- Stop-limit reliance during stress: stop-limits can avoid slippage in calm markets but can fail to execute when liquidity thins or price jumps across the limit.

- Over-optimization: selecting a trail that fits historical noise perfectly often fails out of sample. Robustness matters more than marginal backtest gains.

Interaction with Position Sizing and Portfolio Risk

Trailing stops operate within a broader risk framework that includes initial stop placement, position sizing, and portfolio-level exposure. If initial risk is defined by an initial stop, the position size is often calculated relative to that initial distance. As the trail moves, the risk on remaining capital changes. Some practitioners reduce position size when the trail tightens significantly, while others maintain size until exit. Each choice affects volatility of returns, correlation between positions, and drawdown depth.

Portfolio construction also matters. Simultaneous positions can trigger exits together during broad market moves, creating correlated slippage. If many positions use similar trailing logic and reference the same volatility regime, exits may cluster. This is a portfolio property, not a flaw in a single position’s trailing logic.

Timeframe and Market Considerations

Trailing stops function differently across horizons and asset classes:

- Intraday trading: minute-by-minute updates can keep risk tight but expose the process to microstructure noise, spikes around auctions, and algorithmic flow. Liquidity during certain intervals is uneven, which affects fills.

- Swing and position horizons: end-of-day updating and close-based references can reduce noise, recognizing that overnight gaps are significant sources of slippage. Stop-market orders placed for the next session can trigger at the open with uncertain fills.

- Asset behavior: single-name equities gap more often than major currency pairs. Futures have contract-specific liquidity patterns. Crypto trades continuously, but liquidity varies by venue and time. These differences shape a pragmatic choice of trail distance and order type.

It is worth recognizing the path dependency of trailing logic. Two trades that reach the same eventual price can produce different outcomes depending on the sequence of highs and lows that occurred along the way.

Realistic Expectations and Performance Characteristics

Trailing stops can produce three broad categories of outcomes:

- Quick stop-outs: trades that never gain momentum will hit the trail near the initial stop, reflecting normal noise rather than error.

- Intermediate givebacks: trades that advance, then reverse modestly, exit with partial profit. Over many samples, these define the central tendency of the exit distribution.

- Outliers: a small subset may advance significantly before the trail is hit. These rare contributions often drive a disproportionate share of total returns in trend-accommodating environments.

The balance among these categories depends on volatility, trend persistence, and the trail’s sensitivity. A highly responsive trail decreases average giveback but may reduce the frequency of outliers. A wider trail increases the chance of capturing large runs but tolerates deeper interim drawdowns. The desired balance is contextual and should align with capacity for variance and drawdown at the portfolio level.

Backtesting and Validation Considerations

When evaluating trailing stops with historical data, several practical issues arise:

- Bar-level ambiguity: if using candles rather than tick data, the order in which high and low occurred within a bar is unknown. This affects whether the trail was hit before a new high was made.

- Bid-ask spread and liquidity: backtests that ignore spread, partial fills, and queue position tend to overstate performance of tight trails.

- Gaps: modeling gaps requires explicit rules for opening auction mechanics and stop execution logic at the open. Simplified assumptions can bias results.

- Look-ahead risk: any trail that references closing values or indicators must be computed using only data available at the decision time. Using the full day’s range to set an end-of-day trail introduces bias.

- Parameter stability: a trail that works only for a narrow range of parameters is fragile. Moderate stability across parameter values and regimes is a healthier sign.

These considerations do not invalidate trailing stops. They simply emphasize that a seemingly small implementation detail can change realized outcomes materially.

Psychological Benefits and Limits

Trailing stops can reduce the need to make stressful discretionary decisions during reversals. The presence of a predefined exit threshold can help avoid paralysis after a strong run or sudden news shock. They also provide a common language for discussing risk within teams. However, they are not a cure-all. Rules can be overridden, and rules that are not understood deeply are rarely followed during stress. Clear documentation and consistent application tend to matter more than small tactical tweaks.

Special Topics and Variations

Breakeven and Partial Exits

Some practitioners move stops to breakeven after a certain gain or scale out as the trail tightens. This reduces the chance of turning a winner into a loser but also changes the shape of outcomes and can limit participation in larger trends. The effect depends on how often trades retrace to entry before extending.

Close-Only vs Intraday Trails

A close-only trail updates and triggers based on closing data. It reduces intraday whipsaw but risks larger gap-related slippage. Intraday trails are more responsive but deal with more noise. Both approaches are defensible depending on objectives and constraints.

Combining Trailing Stops with Other Risk Controls

Portfolio-level drawdown limits, volatility targeting, or exposure caps can complement trailing stops. The combination shapes total risk more than any single rule. Coherence across rules is more important than any one parameter choice in isolation.

Applying Trailing Stops in Real Scenarios

Several contexts show how trailing stops behave under real constraints:

- Earnings or event risk for equities: price can gap across a trail at the open. Stop-market orders will execute near the open price, which may be far from the prior close. Stop-limit orders may not execute if the opening trade skips the limit. Planning for event-driven gaps is central to expectation management.

- Trend acceleration in futures: when ranges widen, ATR-based trails move farther from price, reducing the chance of premature exit but increasing giveback if reversal occurs.

- Overnight sessions: continuous markets can adjust trails during quiet hours, then trigger on low liquidity prints. Some traders prefer to update trails only during primary sessions to manage slippage risk. This is a process design choice, not a rule of correctness.

- FX and crypto around data releases: real-time updates can cause rapid triggers and significant slippage. Post-event stabilization windows are sometimes used operationally, though that introduces its own risks.

These scenarios highlight that the rules are only as effective as their operational fit with the instrument’s trading mechanics.

Frequently Raised Misconceptions

- Trailing stops prevent large losses: they limit the giveback from a favorable point, not necessarily from the entry. Large losses are still possible if the trade never advances or if a severe gap occurs.

- Trailing stops work best on every time frame: performance depends on the ratio of trend to noise for the chosen horizon. There is no universal best time frame.

- A precise percentage is optimal: small parameter differences rarely matter as much as robust implementation and consistent adherence. Stability across a range of values is usually more informative than a single fitted setting.

- Indicator choice determines success: indicators are tools for defining distance and reference. Process quality, execution, and risk limits usually have a larger impact than the specific indicator selected.

Building a Coherent Trailing Stop Process

To integrate trailing stops coherently within a broader approach, align the trail with the trade’s thesis, time horizon, and the instrument’s volatility characteristics. Document the following elements to avoid ambiguity:

- Reference price or indicator used to update the trail.

- Distance definition, including units and parameters.

- Update frequency and session rules.

- Order type upon trigger, including any limits or protections.

- Portfolio interactions, such as exposure caps when multiple positions trail simultaneously.

- Procedures for extraordinary events, such as halts, auctions, or major news releases.

Clear documentation reduces decision friction and supports consistent execution under pressure. It also makes post-trade analysis more meaningful, since exits can be evaluated against stated rules rather than reconstructed from memory.

Conclusion

Trailing stops provide a disciplined method to govern exits after a trade has moved favorably. By defining an allowed giveback that ratchets with the position’s progress, they help shape the loss profile and manage drawdowns from peak equity. Their real value comes from correct specification and reliable execution rather than a promise of better average returns. When applied with an understanding of market mechanics, volatility, and portfolio context, trailing stops can contribute to the durability of a risk management process.

Key Takeaways

- Trailing stops are dynamic exits that move with favorable price changes and hold steady during adverse moves, capping giveback from prior peaks.

- Order type, liquidity, and market microstructure strongly influence realized outcomes, especially during gaps or fast markets.

- Construction choices, such as distance, reference, and update frequency, balance responsiveness against noise tolerance.

- Trailing stops shape the distribution of outcomes and drawdowns but do not guarantee profits or superior average results.

- Coherent documentation and consistent implementation matter more than minor parameter optimizations when integrating trailing stops into a broader risk framework.