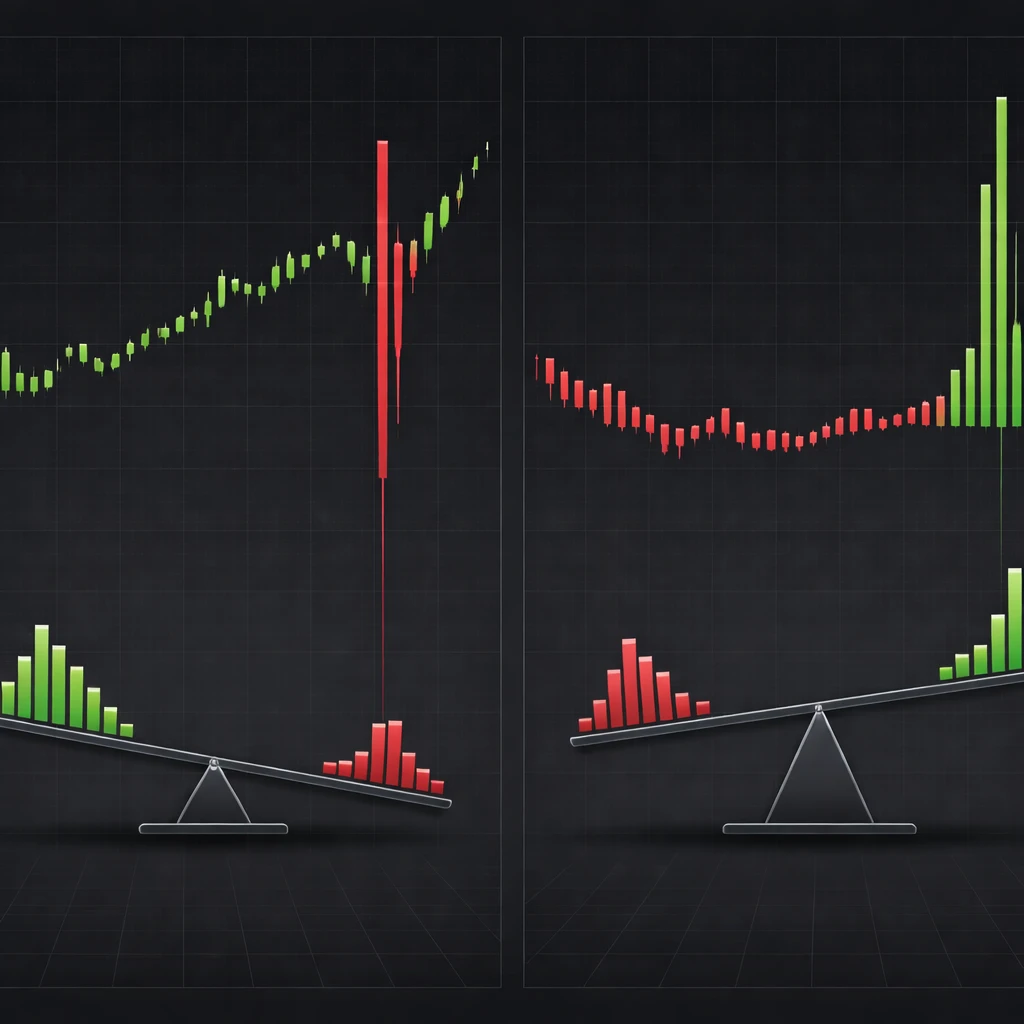

Many traders fixate on win rate, the percentage of trades that finish with a profit. The attraction is obvious: a high hit rate feels comfortable, appears consistent, and is easy to advertise. Yet win rate alone does not tell you whether a method protects capital or has a positive expectancy. A trading process can win most of the time and still be fragile, while another can lose frequently and still compound effectively over long horizons.

This article explains why win rate alone is misleading, how it relates to payoff size and variance, and why focusing on the full risk and reward profile is essential for capital preservation and long-term survivability.

What Win Rate Measures, and What It Ignores

Win rate is the fraction of trades that close profitably. It is typically expressed as a percentage, such as 60 percent. While straightforward, win rate omits several critical dimensions of risk and return:

- It ignores how large the winners are relative to the losers.

- It ignores the dispersion of outcomes, including the probability and severity of streaks.

- It ignores the effect of transaction costs, slippage, and financing.

- It ignores the frequency and timing of trades, which affect compounding and drawdown dynamics.

Because win rate does not incorporate payoff magnitude, two methods with the same hit rate can have markedly different capital trajectories. Likewise, two methods with very different win rates can share the same expected profit per trade when measured correctly.

Expectancy: Linking Win Rate to Payoff Size

To judge whether a trading process has an edge, one needs to combine the hit rate with the average sizes of winning and losing trades. The standard metric is expectancy, often expressed in risk units per trade. If W is the win rate, AW is the average win, and AL is the average loss, then

Expectancy per trade = W*AW − (1 − W)*AL.

This definition already shows the limitation of focusing on W in isolation. Expectancy rises with win rate if average win and average loss are held constant, but expectancy can fall even as win rate rises if the average loss grows faster or the average win shrinks.

It is often convenient to work in R-multiples, where 1R is the initial risk per trade. Suppose a method risks 1R on each position. If the average gain on winners is rR, where r = AW/AL, the break-even win rate is

Break-even W = 1 / (1 + r).

When average wins are equal to average losses (r = 1), break-even W is 50 percent. If average wins are twice the average losses (r = 2), break-even W falls to 33.3 percent. If average wins are half the average losses (r = 0.5), break-even W jumps to 66.7 percent. The same win rate means very different things depending on the payoff ratio.

Example 1: High Win Rate, Negative Payoff Skew

Consider a method with an 80 percent hit rate. On winners it captures 0.5R, and on losers it gives back 2R. Expectancy is

0.80*0.5R − 0.20*2R = 0.40R − 0.40R = 0.

Before costs, this method only breaks even. After accounting for slippage and commissions, expectancy becomes negative. Worse, the negative skew means that a small number of losses erase many gains. Over a short sample, it can look stable because most trades win. Over a long sample, clustered losses can produce deep drawdowns.

Example 2: Low Win Rate, Positive Payoff Skew

Consider a method with a 35 percent hit rate. Average win is 3R and average loss is 1R. Expectancy is

0.35*3R − 0.65*1R = 1.05R − 0.65R = 0.40R per trade.

This method loses most of the time, but the winners are large enough to produce positive expectancy. The path can be psychologically challenging because of frequent losses and longer losing streaks, yet capital can grow if risk is controlled and the edge persists.

Why Win Rate Alone Misleads Risk Control

Risk control is about limiting the chance of ruin and keeping drawdowns within tolerable bounds. A high win rate can hide structural vulnerabilities that are important for survivability:

Hidden tail risk. Methods engineered to win frequently often achieve that result by truncating gains early and tolerating large or occasional uncapped losses. The distribution is negatively skewed. Most days are calm and profitable, but rare events cause large step-downs. A high hit rate does not compensate for heavy left-tail risk.

Cost sensitivity. Approaches with small average wins rely heavily on a high hit rate to stay above break-even. Incremental costs, such as a small widening of spreads or increased slippage during volatile periods, can flip expectancy from positive to negative without any change in win rate.

Regime dependence. A process optimized for a high hit rate under one market regime may deteriorate when volatility or liquidity shifts. Hit rate can remain superficially high while losses grow because trade exits become more expensive or adverse gaps increase the average loss.

Behavioral pressure. High win rate methods feel comfortable until they do not. The first large loss after a long run of small gains can prompt reactive changes, such as widening stops or adding to losing positions, that amplify risk precisely when discipline is most needed.

Path Risk: Volatility of Outcomes and Drawdowns

Two processes with the same expectancy can produce very different paths. The path is shaped by win rate, payoff ratio, and the dispersion of outcomes.

With a lower win rate, longer losing streaks are more probable. For a simple Bernoulli model with independent trades, the probability that any specific sequence of k consecutive losses occurs is (1 − W)^k. With W = 0.35, the probability of five losses in a row at a particular position in the sequence is 0.65^5, roughly 11.6 percent. With W = 0.80, the same calculation yields 0.2^5, which is 0.032 percent. In practice, dependence between trades and variable payoff sizes complicate this picture, but the directional lesson remains: lower hit rates bring more frequent and longer losing streaks, even when expectancy is healthy.

Drawdowns are a function of both the depth of single losses and the clustering of adverse outcomes. A high hit rate combined with occasional losses of 3R to 5R can produce deeper drawdowns than a lower hit rate method where losses are kept close to 1R. The larger the loss multiple relative to the typical gain multiple, the more sensitive the equity curve becomes to streaks and gaps.

Impact on Risk of Ruin

Risk of ruin depends on edge and volatility, as well as the fraction of capital risked per trade. For a given position size, negative skew and fat left tails increase the probability of crossing a ruin threshold. Two methods with identical win rates can have very different ruin probabilities if one has a large variance of outcomes or infrequent but oversized losses. Conversely, two methods with the same expectancy can still exhibit different ruin probabilities if one achieves its edge through a small hit rate and large winners, and the other through a high hit rate and thin winners with occasional large losses.

Costs, Slippage, and the Illusion of Precision

Transaction costs, slippage, and financing charges do not show up in a headline win rate but directly affect expectancy. Their impact is especially acute when average profits per winning trade are small.

Suppose a scalping-style process shows a 75 percent win rate with an average gross win of 0.15R and an average loss of 0.50R. Before costs, expectancy is 0.75*0.15R − 0.25*0.50R = 0.1125R − 0.125R = −0.0125R. Even a small improvement in hit rate would be required to push this positive, and any increase in friction would push it further negative. The reported win rate gives a false sense of robustness because the edge, if any, is thinner than the measurement error introduced by costs.

By contrast, a process with larger winners relative to losers is less sensitive to small changes in costs. The hit rate might be lower, but as long as the payoff ratio remains favorable, the margin above break-even can absorb modest slippage without flipping the sign of expectancy.

Why This Concept Is Critical for Capital Protection

Capital protection does not come from a high percentage of winning trades. It comes from controlling the size of losses, maintaining a positive expectancy after costs, and keeping the volatility of outcomes within sustainable bounds. Emphasizing win rate can lead to poor decisions such as holding losses to preserve a hit rate, exiting winners prematurely, or increasing size after small strings of gains because recent results appear consistent.

Longevity depends on resilience to adverse sequences. A method with modest win rate but well-contained losses can often survive volatility spikes and liquidity shocks more reliably than a high win rate method that accepts occasional outsized losses. Protecting capital also requires acknowledging that markets are nonstationary. A hit rate measured during a stable period can deteriorate quickly when the distribution of returns changes. Expectancy that incorporates payoff size and costs is a sturdier compass.

Applying the Insight in Real Trading Workflows

In practice, treating win rate as one component of a broader diagnostic is more informative. The following activities illustrate how the concept translates into day-to-day evaluation of a process, without implying recommendations:

- Measure outcomes in R-multiples. Normalize gains and losses by initial risk per trade. Track the average win (in R), average loss (in R), and resulting payoff ratio.

- Compute expectancy after costs. Include commissions, spreads, slippage, and financing to estimate net expectancy using the formula W*AW − (1 − W)*AL.

- Assess dispersion, not just averages. Document the distribution of R-multiples, including the largest loss and the frequency of multi-R adverse outcomes such as gaps or rapid reversals.

- Examine path sensitivity via scenarios. Simulate sequences with the observed W, AW, and AL. Study how often losing streaks of length k occur for k between 3 and 10, and how they affect drawdown when combined with plausible clustering.

- Monitor stability across regimes. Segment results by volatility regimes, liquidity conditions, or time-of-day patterns to see whether win rate or payoff ratio are regime dependent.

Case Study: Same Expectancy, Different Paths

Consider two hypothetical processes, each risking 1R per trade and each with expectancy of 0.20R per trade after costs.

Process A: W = 70 percent, AW = 0.714R, AL = 1R. Expectancy = 0.70*0.714R − 0.30*1R ≈ 0.50R − 0.30R = 0.20R. This process wins often but with small average gains.

Process B: W = 40 percent, AW = 2.0R, AL = 1R. Expectancy = 0.40*2.0R − 0.60*1R = 0.80R − 0.60R = 0.20R. This process wins less often but with larger average gains.

Both have the same average edge per trade, but their risk profiles differ. For Process A, the chance that any given position in a sequence is the start of six consecutive losses is 0.30^6, roughly 0.00073. For Process B, the analogous probability is 0.60^6, roughly 4.67 percent. Process B therefore faces more frequent streaks of losses and more psychological pressure, but its losses are consistently around 1R, and there is little hidden tail risk if discipline is maintained. Process A experiences fewer losing streaks, yet if a market gap or liquidity shock causes losses larger than 1R, the small average wins leave less cushion. If occasional losses expand beyond the planned 1R due to slippage or execution risk, the apparent stability can be deceptive.

The lesson is that equal expectancy does not mean equal survivability. Evaluating a process requires studying both payoff asymmetry and the distribution of streaks, not its win rate in isolation.

Common Misconceptions and Pitfalls

- Equating a high win rate with a good strategy. Without considering payoff ratios and costs, a high hit rate can mask negative expectancy and fragile tail behavior.

- Optimizing stops solely to raise hit rate. Tightening or widening exits to boost win rate can invert payoff skew, producing many small wins and rare large losses that dominate long-term outcomes.

- Averaging down to protect win rate. Adding to losers can improve the chance of exiting at a small gain during calm periods, but it concentrates risk and increases exposure to rare but severe drawdowns.

- Ignoring sample size and regime shifts. Short samples with a high hit rate are not conclusive. Hit rates are nonstationary when market conditions change, and small datasets understate streak risk.

- Confusing comfort with robustness. A smooth equity line over a short window may be the byproduct of negative skew. Robustness requires analyzing the worst losses, not only the frequency of wins.

Practical Measurement: From Journal to Numbers

Accurate measurement begins with consistent definitions and recordkeeping. Record each trade’s planned 1R risk, realized result in R-multiples, slippage relative to quote, and any deviations from the plan. With these data, compute:

- Win rate (W): Number of winning trades divided by total trades.

- Average win (AW): Mean of R-multiples for winning trades.

- Average loss (AL): Mean of absolute R-multiples for losing trades.

- Payoff ratio (r): AW/AL.

- Expectancy: W*AW − (1 − W)*AL.

Beyond averages, examine dispersion. The standard deviation of R-multiples per trade offers a first view of variability. The maximum observed loss and the frequency of 2R to 3R losses indicate tail behavior. Segment these statistics by period and market condition to understand when and why the process performs differently.

Finally, examine path properties. A simple exercise is to shuffle historical trades randomly many times and compute the distribution of maximum drawdown for sequences of a fixed length. This reveals how sensitive drawdown is to streaks under the observed W, AW, and AL. The exercise highlights that two processes with similar win rates can have very different drawdown characteristics because of payoff asymmetry and dispersion.

Behavioral Dimensions

Human perception is strongly influenced by frequency of reinforcement. High hit rate methods deliver frequent positive feedback and can feel more manageable. Low hit rate methods demand patience, because losses are common even when the process is sound. Either profile can be viable if expectancy is positive and risk is controlled, but each places different demands on discipline.

Overweighting win rate in decision making can lead to maladaptive behavior, such as refusing to accept small losses to avoid denting the hit rate. A better lens is to judge decisions by whether they preserve the intended payoff asymmetry and keep realized losses aligned with planned 1R risk. The objective is not to win often for its own sake. The objective is to structure trades so that the distribution of results supports survivability and controlled growth over time.

Conclusion

Win rate tells you how often a trade finishes green or red. It does not reveal how much is gained or lost, how variable the outcomes are, or how the path will feel during inevitable streaks. Focusing on win rate in isolation invites fragile designs that prioritize comfort over robustness. By integrating payoff size, costs, and dispersion into expectancy, one can evaluate risk and reward with greater realism and protect capital more effectively against adverse sequences and tail events.

Key Takeaways

- Win rate alone does not determine edge; expectancy depends on both frequency and magnitude of outcomes.

- High hit rates can coexist with negative skew and fragile tail risk, while lower hit rates can compound if payoff ratios are favorable.

- Costs and slippage erode thin edges and can turn a high win rate process into negative expectancy.

- Survivability depends on drawdown behavior and variance, not the headline percentage of winning trades.

- Evaluate processes using R-multiples, payoff ratios, net expectancy, and path analysis rather than win rate in isolation.