Risk management in trending markets raises a central question: how much loss risk is being accepted for the potential continuation of the trend, and how asymmetric is that trade-off under real market conditions. Risk/reward analysis provides a disciplined way to quantify that relationship before capital is exposed. The core idea is simple but powerful. Define a planned loss if the trade thesis fails, compare it to reasonable ranges of potential gain if the trend persists, and judge whether the imbalance is sufficient to justify the exposure. The details are where discipline is won or lost.

Defining Risk/Reward in Trending Markets

In any market, risk refers to the distribution of adverse outcomes relative to capital at risk, while reward refers to the distribution of favorable outcomes. In trending markets, the distribution is commonly skewed. Losses can be frequent and small when pullbacks are choppy, with occasional large gains when the trend extends. Alternatively, losses can become large and abrupt during sharp reversals or gaps that jump over planned exits. A sound definition therefore distinguishes between the planned loss and the realized loss, which may differ when price moves discontinuously.

For clarity, risk/reward analysis in a trend typically relies on four building blocks:

- Initial or planned risk: the distance between the entry and the invalidation level that would disconfirm the trade thesis. Many practitioners express this in currency terms or as a fraction of account equity, but the concept is independent of sizing.

- Realized risk: the loss actually experienced, which can exceed the plan due to slippage, gaps, or liquidity constraints.

- Potential reward range: plausible favorable movement if the trend continues. In a trend, this can be open ended, which complicates estimation and encourages scenario ranges rather than a single target.

- Probability structure: the likelihood of various outcomes. A high reward multiple with very low probability can have lower expectancy than a moderate multiple with a higher probability of success.

Risk/reward in a trend is therefore not a single ratio. It is a scenario set that links planned loss, potential gain, and likelihoods under current volatility and liquidity conditions. Many analysts express outcomes in R-multiples, where 1R equals the initial planned risk. An outcome of +4R indicates a gain four times the initial risk, while an outcome of −1R indicates a full planned loss. This notation standardizes evaluation across different instruments and position sizes.

Why Risk/Reward Matters for Capital Protection and Survivability

Long-term survivability requires that capital drawdowns remain within tolerable limits during unlucky sequences. Trending markets can produce sequences of small losses interspersed with occasional large gains, or they can flip into mean-reverting behavior that punishes trend-following logic. Without prior control of risk/reward, a trader can be exposed to drawdowns that grow faster than the equity can recover.

The link between risk/reward and survivability operates through three channels:

- Variance control: The variance of returns depends on both the size of losses and their frequency. Keeping the planned loss small relative to capital reduces variance even when the win rate is modest.

- Expectancy discipline: A positive-expectancy process requires that the weighted average of outcomes remains above zero after costs. If the average losing trade is near −1R and the average winner is near +2R or greater, the break-even hit rate may be lower than 50 percent. Conversely, if winners are truncated, the required hit rate climbs.

- Risk of ruin containment: The probability of a large drawdown rises as the loss size and loss frequency rise, especially under correlation and regime shifts. Effective risk/reward planning restricts the capital fraction exposed to any single thesis about a trend.

Protecting capital is not achieved by avoiding all losses. It is achieved by shaping the distribution of outcomes so that typical losses are limited and occasional favorable runs can offset them. Trends provide the potential for asymmetric payoffs, but only if the unfavorable tail is managed.

Characteristics of Trending Markets That Shape Risk/Reward

Trends are not uniform. They alternate between expansion phases and consolidation phases, and they often display clustering of volatility. Several features of trends complicate risk/reward evaluation:

- Volatility regime shifts: During acceleration, true range expands and slippage risk rises. A stop that was appropriate during a quiet phase may be too tight or may be overrun when volatility changes.

- Pullback depth and noise: Even orderly trends contain countertrend movement. If pullbacks regularly reach a certain depth, stops placed inside that noise band will be triggered frequently, reducing the realized reward even when the larger trend remains intact.

- Gap and liquidity risk: Strong trends can gap through levels on news or during off-hours sessions. Realized loss can exceed planned loss when exits are skipped by the next available price.

- Late-stage extension: Trends often appear most convincing near exhaustion. Risk/reward can deteriorate if the entry occurs far from the last consolidation because initial risk grows while incremental reward compresses.

- Correlation and crowding: In cross-asset trends, correlated instruments may move together. Risk exposure aggregates across positions, turning several independent-looking trades into a single thematic bet.

These features imply that risk/reward analysis should be conditioned on recent regime behavior. A static loss distance and a fixed reward assumption are unlikely to be accurate across different volatility states.

Measuring Risk and Reward in Practice

Although no single measure fits all instruments, a structured approach can make the analysis more reliable.

- Define the invalidation level: Before entry, identify the price level that would logically disconfirm the trend thesis. This is the anchor for the 1R definition. It might be beyond a recent swing level, outside a volatility envelope, or below a structural threshold. The key is internal consistency with the trend hypothesis.

- Translate to capital terms: Convert the price distance between entry and invalidation into a monetary amount. This clarifies how much capital is exposed to the single thesis.

- Build a reward window: Instead of a single target, define a range of plausible favorable extensions if the trend continues. The range can be informed by prior trend legs, measured move symmetry, or volatility scaling. Use conservative and optimistic cases, then test sensitivity to both.

- Consider discontinuities: Note where gaps are likely. For example, instruments that trade around earnings announcements, macro releases, or weekend risk may have greater slippage potential. The realized loss distribution should include a tail that exceeds 1R.

- Estimate expectancy: Combine hit-rate assumptions with reward multiples across scenarios. Expectancy is the weighted average outcome after costs. Even rough estimates can prevent exposure to poor asymmetry.

This process does not require prediction. It requires defining what failure looks like, what success could plausibly deliver, and whether that imbalance aligns with prudent capital exposure.

Applying the Concept in Real Trading Scenarios

The following stylized examples show how risk/reward thinking changes as trend conditions evolve. These are illustrations, not recommendations.

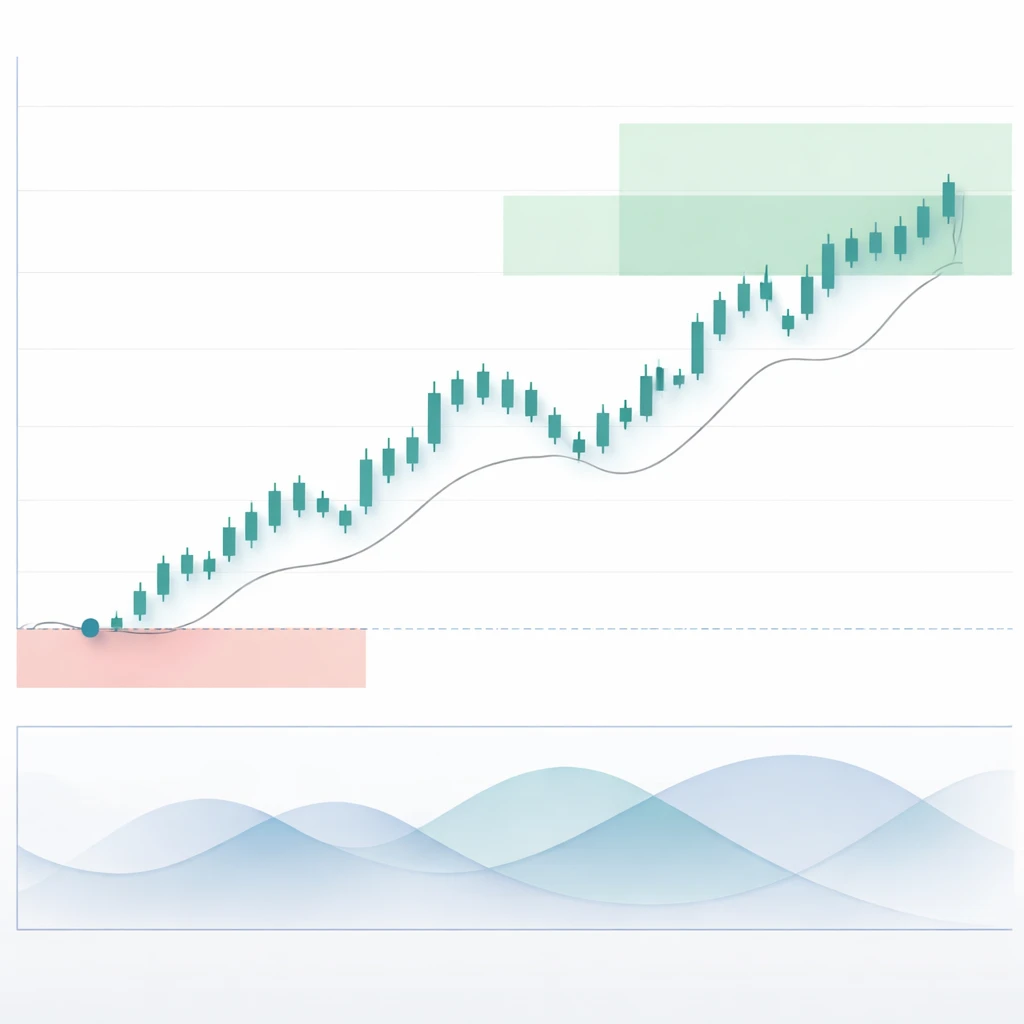

Example 1: Continuation within an Established Uptrend

Imagine an instrument has been rising for several weeks, with pullbacks of 2 to 3 percent followed by higher highs. A participant considers an entry during a new upswing and places invalidation just below the most recent higher low. If the entry to invalidation distance is 2 percent, that defines 1R. If a reasonable continuation leg, based on prior legs, is 6 percent, then a conservative reward case is +3R. An optimistic case might be +5R if momentum persists. The expectancy then depends on the perceived hit rate. For instance, with a 40 percent success probability and average win of +3R against a full loss of −1R, the expectancy is positive in R-terms even with more losses than wins.

The practical difficulty arises when volatility expands. A stop that sits just below the prior low may be reached intraday by noise that is larger than earlier pullbacks. Realized losses can compound if several attempts occur during a choppy consolidation. The reward side remains present, but the path to reach it becomes rough, changing the effective hit rate and the average loss multiple due to stop-outs.

Example 2: False Breakout During a Trend

Consider a strong trend that pauses, builds a tight range, and then breaks upward. False breaks are common when liquidity concentrates around the range. Suppose the entry occurs on the break and invalidation is placed just below the broken boundary, defining 1R as 1.5 percent. If the break fails and price returns to the range, slippage may add an extra 0.2 to 0.5 percent depending on the instrument, magnifying the realized loss above 1R. On the upside, if the break holds and the trend extends by 4 to 5 percent, the potential reward is roughly +3R. However, the probability of a genuine continuation versus a trap is uncertain and regime dependent. Risk/reward analysis forces the question: is the tail risk of a failed break with slippage properly reflected in the plan.

Example 3: Late-Stage Trend Extension

Suppose a trend has already traveled far without a significant pullback. The distance to a logical invalidation line has widened to 4 percent. If the next leg higher is likely to be only 3 to 4 percent before consolidation, the conservative reward may be +1R, with an optimistic case near +1.5R. The asymmetry is weak. Even if the hit rate is high during the final push, a series of small positive outcomes may not compensate for occasional full losses, especially once slippage or a sharp reversal is added. This profile can erode expectancy even while the trend still looks strong to the eye.

Common Misconceptions and Pitfalls

Several recurring errors stem from misunderstanding how risk and reward interact in trends.

- Confusing potential reward with expected reward: A trend can travel far, but the expected reward must reflect probability. Rare, very large winners cannot carry a process that produces frequent full losses with low hit probability and added costs.

- Believing that a higher nominal reward-to-risk ratio is always better: A 5R potential with a 10 percent chance can be inferior to a 2R potential with a 40 percent chance. Expectancy, not the headline multiple, governs sustainability.

- Ignoring volatility regime shifts: Stops calibrated to a quiet phase often underestimate adverse excursions after regime change. This leads to repeated stop-outs or larger than planned losses when levels are jumped.

- Moving stops to breakeven prematurely: Reducing open risk can be prudent, but moving a stop too soon in a noisy trend truncates winners and increases the ratio of small losses to small wins. The result is a distribution with a low average win multiple, which pushes the break-even hit rate higher.

- Chasing late trend extensions: When the distance to a clear invalidation has grown, the initial risk increases precisely when marginal reward may be diminishing. The visual strength of the move can obscure a deteriorating asymmetry.

- Underestimating gap risk: Planned risk assumes continuous pricing. News-driven gaps, earnings events, and thin liquidity sessions can cause exits to fill far from planned levels. Realized loss can exceed the 1R assumption.

- Overlooking correlation: Exposures that share the same trend driver behave as a single trade when stress arrives. The portfolio-level risk/reward can be far worse than the single-position analysis suggests.

- Hindsight anchoring in backtests: Selecting examples where trends unfolded perfectly and then judging risk/reward ex post produces optimistic estimates. Ex-ante planning must accept wider uncertainty and a less tidy distribution of outcomes.

Scenario Thinking and Ex-Ante Planning

A disciplined risk/reward process is most effective before any position is taken. Ex-ante planning reduces the influence of emotion and recency bias. A practical approach is to outline three scenarios with rough probabilities that sum to one: favorable trend continuation, noisy consolidation, and adverse reversal. Each scenario maps to an outcome in R-multiples. Even basic scenario weights can improve decision quality by forcing explicit trade-offs rather than relying on a single best case.

For example, a participant might judge a 35 percent chance of +3R continuation, a 45 percent chance of choppy behavior resulting in −0.7R due to partial exits, and a 20 percent chance of a full −1.2R including slippage. The expectancy is then the weighted sum of these outcomes. If costs are added and the result is marginal, the plan can be reconsidered. This is not an instruction to change the trade. It is a description of how scenario analysis can highlight hidden fragility.

Expectancy, Hit Rate, and Distribution Shape

Expectancy is the average outcome per trade after costs. In trending markets, many processes aim for a lower hit rate paired with larger average wins, creating positive skew. However, if winners are truncated by tight management or if regime shifts reduce trend persistence, the average win multiple declines. The hit rate then must rise to compensate, which can be difficult if the underlying method relies on continuation rather than mean reversion.

Another consideration is the dispersion of outcomes. Two methods can have the same expectancy but different variances. A method with infrequent large gains and many small losses may produce long equity plateaus and sharp jumps. A method with more frequent modest gains and modest losses may produce smoother paths but lower top-end potential. Survivability depends not only on the mean but also on the variance and tail risk of that distribution, especially when leverage or concentration magnifies adverse sequences.

Tracking R-Multiples, MAE, and MFE

Robust risk/reward evaluation benefits from measurement. Three simple metrics are informative:

- R-multiples for each closed trade: Standardizes performance across instruments and time. Over a sample, the average R and its variance reveal whether the risk budget is being used efficiently.

- Maximum Adverse Excursion (MAE): The largest unrealized loss experienced before the trade is closed. Comparing MAE to the planned 1R reveals whether stops are placed inside typical noise or far beyond it.

- Maximum Favorable Excursion (MFE): The largest unrealized gain before exit. If MFE frequently reaches +3R but realized results average +1R, management practices are truncating winners. If MFE rarely exceeds +1.5R, the trend environment may not support the assumed reward multiples.

Analyzing MAE and MFE across volatility regimes helps distinguish method issues from market regime effects. For instance, a burst of wider MAE without a similar increase in MFE suggests that stop calibration is out of sync with the new regime.

Timeframes, Instruments, and Liquidity

Risk/reward dynamics vary by timeframe and instrument. Shorter timeframes amplify noise and friction costs. Stops tend to be closer to current price, so the 1R distance is smaller in price terms but can be larger relative to typical microstructure noise. This can produce lower realized reward multiples unless trend impulses are strong enough to overcome costs and noise.

Longer timeframes may support larger reward multiples if trends persist, but gap risk becomes more relevant, and economic or fundamental events can cause discontinuities. Instruments also differ in liquidity profiles. Highly liquid index futures may slip less under normal conditions than thin small-cap equities, but both can move sharply during stress. Currencies might trade continuously across sessions with fewer gaps, while single-name equities can jump at the open after announcements. The realized loss distribution should reflect these features rather than assuming a uniform 1R cap.

Portfolio-Level Risk/Reward in Trending Phases

When multiple positions share the same driver, such as a global risk-on environment, their risk and reward are correlated. A favorable trend can lift all boats, creating a cluster of winners. The reverse can produce a cluster of losses. Portfolio-level survivability therefore depends on how many independent themes are active. Treating each position as a separate risk event can understate the total exposure to a single macro trend. A more complete analysis aggregates scenario outcomes at the portfolio level and compares the worst-case cluster loss with acceptable drawdown limits.

Costs, Slippage, and Realized Outcomes

Transaction costs and slippage transform theoretical risk/reward into realized results. In trends that surge and pull back quickly, entries and exits often occur during fast moves when spreads widen. The difference between planned and achieved prices can erode both sides of the distribution. If the average loss expands from −1.0R to −1.2R while the average win contracts from +3.0R to +2.6R, the expectancy can flip sign even if the hit rate is unchanged. Measuring this slippage and adjusting the scenario set helps maintain realism in planning.

Behavioral Pressures During Trends

Trends are visually persuasive. When price moves strongly in one direction, fear of missing out encourages late entries that weaken asymmetry. During consolidations, fear of loss can cause premature exits that truncate winners. A clear pre-defined risk/reward framework reduces the influence of these pressures by creating objective reference points for failure and for plausible reward. Without such a framework, decisions gravitate toward the most recent price action rather than the planned distribution of outcomes.

Role of Trailing Exits and Partial Realization

Many management approaches attempt to balance open-ended reward with protection against reversals. For example, trailing exits follow price to reduce open risk as a trend advances, while partial realization realizes some gains early and leaves a remainder to capture potential extensions. Both mechanisms reshape the outcome distribution. Trailing exits can prevent a large give-back but may cut off the tail of very large wins. Partial realization can raise hit rate on smaller wins but reduces the average multiple for the remaining position. The suitability of either approach depends on the observed MFE and the frequency of long extensions in the specific market and timeframe.

Regime Awareness and Adaptation

Trend quality varies across time. Periods of smooth, directional flow support reward multiples that are larger and more frequent. Periods dominated by mean reversion within wide ranges produce more whipsaws and smaller realized wins. Risk/reward assumptions that were valid during strong momentum may not hold during indecisive phases. Monitoring a small set of regime indicators, such as realized volatility, average swing length, and the ratio of MAE to MFE, can inform whether current conditions resemble prior periods that supported a given asymmetry. This is an observational statement rather than a prescription to change methods.

Protecting Capital and Long-Term Survivability

Survivability hinges on limiting the damage of adverse sequences and preserving the chance to participate when the environment turns favorable again. In trending markets, both opportunity and danger are amplified. Opportunity arises from the potential for extended runs that deliver high R-multiples. Danger arises from fast failures, gaps, correlation, and late-stage deterioration of asymmetry. A robust risk/reward framework addresses these points by quantifying initial risk, testing plausible reward ranges, accounting for discontinuities, and evaluating expectancy under realistic hit rates. The result is not a guarantee of positive outcomes but a higher likelihood that capital will endure through unfavorable periods so that favorable periods can matter.

Key Takeaways

- Risk/reward in trending markets is a scenario-based framework that compares planned loss to plausible reward under current volatility and liquidity conditions.

- Expectancy, not headline reward-to-risk multiples, governs sustainability. Probability weights and costs must be included.

- Volatility shifts, gaps, and correlation can enlarge realized losses beyond the initial plan, so tail risk belongs in the analysis.

- Tracking outcomes in R-multiples, along with MAE and MFE, reveals whether management practices align with the environment’s trend quality.

- Capital protection and survivability depend on shaping the outcome distribution so that typical losses are controlled and occasional trend extensions can offset them.