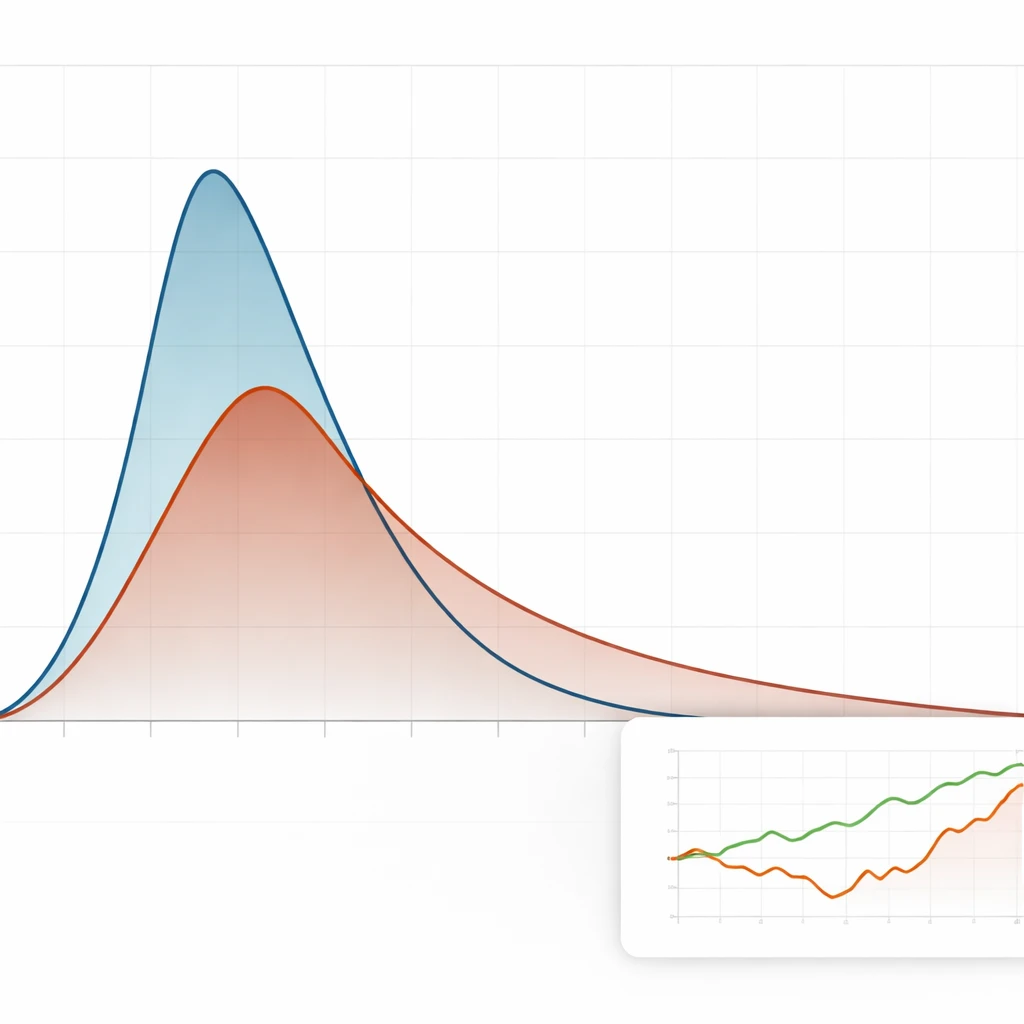

Capital grows through compounding only when losses are kept within limits that the account can recover from. The geometry of losses and gains is not symmetric. A 50 percent drawdown requires a 100 percent gain to reach the prior peak. This simple fact motivates a central idea in risk management. An asymmetric risk profile prefers outcomes where losses are truncated or tightly controlled relative to a more open field for gains. The profile targets a payoff distribution that protects the left tail and preserves the right tail.

What Is an Asymmetric Risk Profile?

Definition. An asymmetric risk profile is a payoff structure in which the potential loss on a position or portfolio is limited or constrained relative to the potential gain, or where loss events are designed to be small and frequent while gains are allowed to be larger when they occur. Positive asymmetry is often described as limited downside with scalable upside. Negative asymmetry is the reverse pattern, where small, steady gains are occasionally interrupted by large losses.

Asymmetry can be embedded in the instrument itself, produced by risk controls, or emerge from the underlying trading logic. A long call option is structurally asymmetric because the maximum loss is the premium while upside is open. A stop-based approach attempts to engineer asymmetry by setting a hard exit level for losses and using a more flexible profit-taking policy. A trend-following logic may create asymmetry by holding into extended moves while cutting losing trades quickly. None of these constitute recommendations. They illustrate how different mechanisms can shape the distribution of returns.

Positive asymmetry is not the same as a guaranteed profit. It is a design choice about how losses are absorbed and how gains are captured. The concept is evaluated over many independent trades or periods. It relies on expectancy, distribution shape, and the speed at which capital can recover from inevitable setbacks.

Why Asymmetry Matters for Risk Control and Survivability

Capital preservation and compounding. Compounding amplifies the cost of drawdowns. Large losses require disproportionate gains to recover, which lengthens the time spent below high-water marks. A profile that limits the depth of losses helps maintain a smoother equity path and reduces the risk of falling below thresholds where behavioral or institutional constraints force liquidation.

Path dependency. The path of returns matters as much as the average return. Two sequences with the same arithmetic average can leave very different ending capital when volatility and drawdowns differ. Asymmetry that cuts off severe left-tail events improves the path by avoiding deep troughs that take many periods to repair.

Risk of ruin. Ruin is the event where capital falls to a level that cannot support the strategy or the margin required. Reducing the probability and magnitude of extreme losses is the most direct way to lower the risk of ruin. Positive asymmetry accomplishes this by capping or compressing individual losses while preserving the potential for episodic large gains that offset many small losses.

Distribution shape and tail control. Returns are not normally distributed in many markets. Fat tails and volatility clustering increase the frequency of extreme moves. Asymmetric profiles that are robust to tail risk are more compatible with these realities than profiles that collect small gains while quietly accumulating exposure to rare, severe losses.

Behavioral robustness. Traders operate under stress. Drawdowns trigger loss aversion, regret, and risk-seeking to recover. Profiles that engineer smaller, more predictable losses reduce the psychological pressure that often leads to rule-breaking. Better behavior is an indirect but important benefit of positive asymmetry.

How Asymmetry Appears in Real Trading Scenarios

Asymmetry arises both from instrument design and from risk process design. The following illustrations show how profiles can differ without recommending any particular approach.

Capped Loss, Uncapped Gain Instruments

Some instruments carry built-in convexity. A buyer of a plain-vanilla call has a maximum possible loss equal to the premium and theoretically unbounded upside if the underlying price rises. This is a textbook example of positive asymmetry. The buyer is paying for that property through the option premium, implied volatility, and time decay. The existence of positive asymmetry in the payoff does not guarantee profitability. The cost of carrying the position may overwhelm the realized gains if the underlying does not move enough.

Stop Placement and Gap Risk

Traders often attempt to engineer asymmetry with stop orders. The idea is to exit quickly when a thesis is invalidated and allow more flexibility on the profit side. This approach faces a practical limitation. Stops are not guarantees. Rapid moves or gaps can cause slippage relative to the stop level. That does not nullify the pursuit of asymmetry, but it highlights that implementation details such as liquidity, news risk, and session gaps affect how closely the realized loss matches the planned loss.

Trend and Mean Reversion Profiles

A trend-oriented logic tends to produce many small losses and fewer, larger gains when trends persist. The loss side is truncated by exits that recognize adverse moves early. The gain side remains open when price runs in the intended direction. Mean reversion often inverts this shape. It can deliver frequent small wins when prices revert quickly, punctuated by occasional large losses when reversion fails. Neither shape is inherently superior across all environments. The point is that strategy logic influences asymmetry and should be evaluated with full awareness of tail behavior.

Hedging and Insurance-Like Profiles

Protective hedges seek to purchase downside protection, converting an otherwise symmetric or negatively skewed profile into a more favorable one. The protection has an explicit cost that drags on returns in quiet periods. The trade-off is a thinner left tail during adverse events. Effective use of hedges depends on the relationship between the cost of protection and the frequency and severity of losses avoided. Overpaying for protection can negate the benefit of asymmetry if it consumes more capital than it preserves.

Portfolio Correlation and Net Asymmetry

Asymmetry should be viewed at the portfolio level. A set of individually asymmetric positions can still produce a poor aggregate profile if correlations spike during stress. Many assets become highly correlated in risk-off conditions. The net result can be a left tail that is fatter than any single position would suggest. Monitoring joint behavior during shocks and evaluating conditional correlations provides a more realistic view of the portfolio’s true asymmetry.

Measuring and Diagnosing Asymmetry

Asymmetry is a property of a distribution. It should be measured with sufficient data and interpreted with care. Several complementary lenses help build a reliable diagnosis.

Payoff Ratio and Win Rate

A common starting point is the payoff ratio, sometimes called the reward-to-risk ratio. If average gains are 2.5 units and average losses are 1 unit, the ratio is 2.5. Paired with win rate, it provides a coarse picture of expectancy. Two profiles can have similar expectancies but very different shapes. For example, a profile with a 40 percent win rate and a 2.5 payoff ratio can have similar average returns to a profile with a 60 percent win rate and a 0.8 payoff ratio. The first has positive asymmetry from larger wins. The second relies on frequent small gains and may hide vulnerability to large losses.

Expectancy at the Trade Level

Expectancy is the average profit or loss per trade. A simple model is E = p × G − q × L, where p is the probability of a gain, q is the probability of a loss, G is average gain, and L is average loss. Asymmetry improves expectancy by lowering L relative to G, or by allowing occasional G values that are multiples of L. However, expectancy by itself can be misleading if the distribution is dominated by rare, extreme outcomes. A strategy that shows a small positive expectancy over short samples may hold a hidden risk of a large negative outlier that reverses months of gains.

It is useful to compute expectancy in risk units, often called R multiples. If one unit of risk is defined by the planned loss on a trade, average gain and loss can be expressed in R. A profile with an average loss of −1 R and an average gain of +2.5 R exhibits positive asymmetry. The realized results depend on slippage, gaps, and discipline, which determine whether the −1 R assumption is actually achieved.

Distribution Shape, Skewness, and Tail Concentration

Statistical moments describe distribution shape. Positive skewness indicates a right tail with occasional large gains. Negative skewness indicates vulnerability to large losses. Kurtosis describes tail thickness. A profile can have positive expectancy but negative skew if gains are steady and losses are rare but severe. This shape often fails during regime shifts when assumptions about mean reversion, liquidity, or volatility break down.

Beyond moments, practical diagnostics include the proportion of total profits generated by the top 5 percent of trades, the worst 5 percent of losses, and the conditional loss beyond a chosen percentile such as conditional value at risk. If the largest 1 or 2 losses erase a large portion of the equity curve, the profile likely has negative asymmetry even if the average looks acceptable.

Drawdown Geometry and Time to Recovery

Asymmetry expresses itself in the shape of the equity curve. Shallow drawdowns that recover quickly are evidence of effective left-tail control. Deep drawdowns with slow recoveries indicate that losses are not sufficiently truncated or that tail events overwhelm the intended structure. It is helpful to examine maximum drawdown, average drawdown, and the distribution of recovery times. Long recovery periods reveal path dependency that exploits compounding in reverse.

Behavioral Dynamics that Destroy Asymmetry

Designing an asymmetric profile is not enough. Execution behaviors often erode the intended shape.

Cutting winners too early. Realized gains become small, and the right tail disappears. The payoff ratio compresses even when the stop policy on losses remains intact.

Letting losers run. Small planned losses become larger realized losses. Gap risk aside, discretionary overrides of exit rules tend to accumulate when traders try to avoid admitting mistakes. The left tail thickens and the risk of ruin rises.

Averaging down without limit. Adding to losing positions in a deteriorating scenario can convert a controlled loss into a portfolio-level event. The asymmetry shifts negative as the potential loss expands faster than any plausible gain on the rebound.

Over-sizing after wins or losses. Variable sizing driven by emotion rather than a defined process undermines the distribution. A large position opened during overconfidence can dominate the sample and overwhelm months of careful left-tail control.

Ignoring implementation frictions. Commission, slippage, borrow costs, financing, and liquidity constraints reduce the realized payoff ratio. Profiles that appear attractive in frictionless backtests can flatten when these frictions are accounted for.

Common Misconceptions and Pitfalls

Myth 1. A high reward-to-risk ratio guarantees profits. Aesthetic ratios are not enough. Without realistic estimates of win rate, transaction costs, and gap risk, the ratio is a statement of intent rather than a description of realized outcomes.

Myth 2. A high win rate is always superior. High win-rate profiles can hide negative skew by booking frequent small profits while occasionally suffering large losses. Without explicit left-tail control, one adverse move can undo many small wins.

Myth 3. Stop losses eliminate risk. Stops are an important tool, but they do not bind the realized exit during fast markets or illiquid conditions. Gaps and price jumps can bypass stop levels. The asymmetry you plan may differ from the asymmetry you realize.

Myth 4. Options always create positive asymmetry. Options can encode attractive payoff shapes, but they are priced. Time decay and implied volatility determine whether that shape is worth the cost. Buying convexity at any price does not ensure a favorable result.

Myth 5. Historical symmetry will persist. Markets change. Correlation structures shift, liquidity varies, and policy regimes evolve. Profiles that relied on a particular market texture can become less effective, especially those with negative skew that depend on mean reversion and stable volatility.

Practical Diagnostics and Monitoring

Reliable assessment of asymmetry benefits from a blend of descriptive statistics and stress thinking. The goal is to understand how the profile behaves under strain, not just on average.

- Track average gain and loss in risk units, win rate, payoff ratio, and expectancy. Observe whether the ratio between average gain and loss remains stable over time.

- Segment trades by market regime or volatility state. Asymmetry that relies on a single low-volatility regime is fragile when volatility expands.

- Compute the contribution of tail events to total returns. If the equity curve depends on avoiding one specific type of shock, the profile is exposed to model error.

- Review maximum adverse excursion and maximum favorable excursion statistics. These describe how far trades tend to move against or in favor before closing. They reveal whether stops are tight enough to enforce the intended loss and whether exits are truncating gains prematurely.

- Run scenario and gap analyses. Map what happens if price moves through levels between sessions or during illiquid periods. Include the possibility that stops fill at worse prices than planned.

- Evaluate portfolio-level behavior under correlation spikes. Individual positions can look benign while the aggregate becomes highly nonlinear in stress.

Diagnostics should be repeated on rolling windows to detect drift. If average loss creeps upward, or if a few trades dominate total profit, the intended asymmetry may be decaying. Monitoring avoids slow degradation that only becomes visible after a large drawdown.

Capital Preservation and Long-Term Survivability

Asymmetry is a practical response to the mathematics of compounding and drawdowns. If a large loss requires a much larger gain to recover, then a profile that limits loss magnitude shortens recovery time. Shorter recoveries keep capital near its compounding frontier and reduce the probability of breaching constraints that force exit.

Survivability also depends on avoiding sequences that cluster losses. Even small losses can accumulate if they occur without relief. Positive asymmetry helps by balancing a run of small losses with occasional larger gains. The profile does not need to predict direction better than chance. It needs to ensure that losing trades cost little relative to what is earned when the market aligns.

Leverage complicates survivability because it introduces margin constraints and amplifies path dependency. A positively asymmetric profile that relies on modest leverage can collapse into negative asymmetry if a few losses trigger margin calls or forced reductions. This is another reason to measure realized losses under stress scenarios and to observe how position sizing rules interact with volatility spikes.

Finally, time is a resource. The measure of a risk profile is not only its average return but also the time required to recover from setbacks. A profile that withstands shocks and restores prior peaks rapidly preserves optionality. Optionality is the freedom to continue operating and to deploy risk in future opportunities. Positive asymmetry is a design principle that supports that freedom.

Closing Perspective

Asymmetric risk profiles do not eliminate uncertainty. They allocate it. The emphasis is on shaping the loss distribution and reserving adequate space for gains. Done well, asymmetry converts an unpredictable sequence of outcomes into a distribution that is more compatible with capital preservation, psychological stability, and long-horizon compounding. The elements are simple to describe and demanding to execute. They require discipline with exits, attention to implementation frictions, awareness of correlation during stress, and a healthy skepticism toward smooth equity curves that may conceal negative skew. Above all, they require respect for the left tail.

Key Takeaways

- Asymmetric risk profiles aim to truncate losses while preserving the potential for larger gains, improving the payoff distribution rather than guaranteeing profits.

- Survivability improves when deep losses are rare and shallow, because recovery requires less time and capital, and behavioral stress is reduced.

- Expectancy, payoff ratio, win rate, and distribution diagnostics such as skewness and tail concentration provide complementary views of asymmetry.

- Implementation details, including slippage, gaps, liquidity, costs, and correlation spikes, often determine whether planned asymmetry becomes realized asymmetry.

- Common pitfalls include cutting winners early, letting losers run, chasing win rate at the expense of tail risk, and assuming that structural or historical symmetry will persist.