Scaling in and scaling out refer to adjusting position size in stages rather than entering or exiting a position all at once. These adjustments are not attempts to predict price. They are tools for controlling risk under uncertainty while information and market conditions evolve. When used with a clearly defined risk budget, staged entries and exits can reduce variance in outcomes, mitigate execution costs, and support long-term survivability by avoiding large, concentrated mistakes.

Foundations: Position Sizing and Risk

Position sizing is the process of deciding how many units of an instrument to hold given a defined risk budget. The budget usually references a maximum capital loss if the initial trade thesis is invalidated. In practice, that budget is implemented via a stop level and a position size that, together, cap the loss in monetary terms. For example, if a trader accepts a maximum loss of 1,000 currency units and the distance between entry and the stop is 2 currency units per share or contract, the maximum size for a single, immediate entry is 500 units.

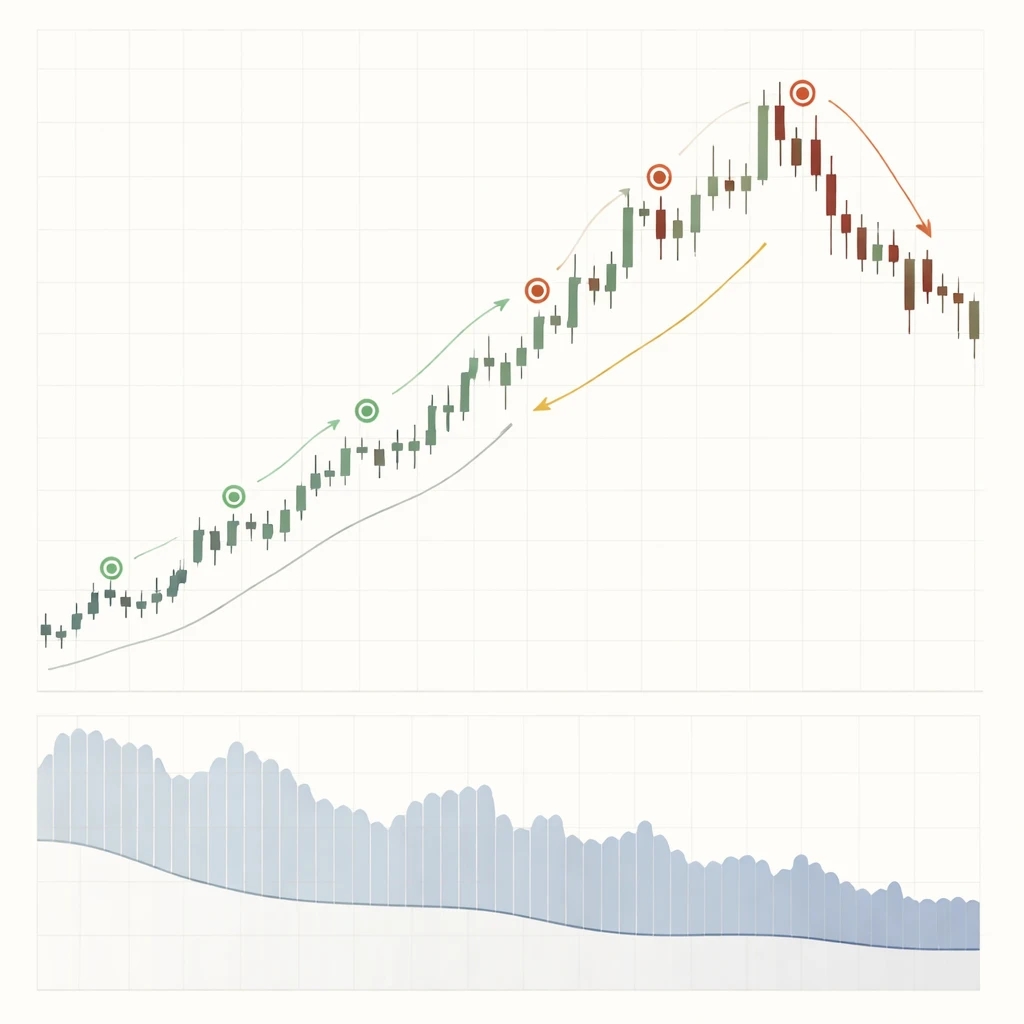

Scaling in modifies this process by splitting the entry into several smaller steps that occur at different times or prices. Scaling out similarly splits the exit into partial reductions rather than a single liquidation. These changes do not alter the underlying thesis by themselves. They alter the path by which risk is deployed and withdrawn. This path dependency matters for capital protection because real markets involve frictions, noise, and gaps that can make one-shot decisions fragile.

Definitions and Mechanics

What is Scaling In?

Scaling in is adding to a position using preplanned increments. The increments can be triggered by time, price movement, volatility changes, liquidity windows, or the arrival of new information. The total of all increments is bounded by an overall size cap and risk budget. The average entry price becomes a weighted average of the filled increments. If no further increments are triggered, the position remains smaller than the theoretical maximum size, which can reduce loss in adverse conditions.

Practical variants include the following:

- Equal-size increments. For instance, three tranches of 200 units each to reach 600 units if all are filled.

- Equal-risk increments. Each addition is calibrated so that the incremental risk contributed by the new tranche equals a fixed amount, accounting for the current stop distance and existing position.

- Information-based increments. A new tranche is added only when additional, independent information increases confidence or when volatility declines in a manner that supports the predetermined risk budget.

What is Scaling Out?

Scaling out is partial profit taking or risk reduction executed in steps. It can be time-based, level-based, or information-based. The objective is not to maximize return on a single trade. The objective is to manage variance, reduce exposure as uncertainty increases, and systematically realize gains while keeping the risk budget aligned with changing conditions. The average exit price becomes a weighted average of the partial exits. A common example is to reduce position size after a favorable move to bring risk back to a desired level or to harvest part of the profit while allowing a residual position to continue if conditions remain favorable.

Average Price and Risk Accounting

Average price arithmetic is straightforward but important for risk accounting. Suppose a first entry is 200 units at 50, and a second entry is 200 units at 52. The total position is 400 units with an average entry of 51. If the stop is 48, the total risk equals 400 times the difference between entry average and stop, which is 400 times 3, or 1,200 currency units. If the plan capped risk at 1,200, this remains consistent with the budget. If additional increments are contemplated, the plan must include how the stop or tranche sizes will adjust so that the cap is not breached.

Why Scaling Matters for Risk Control

Scaling changes the timing and concentration of exposure. The chief benefit is a reduction in the probability of large, early losses due to noise, slippage, or misestimation of the initial stop distance. Several risk control advantages are typical.

- Uncertainty management at entry. Early in a trade, many assumptions are untested. A smaller initial tranche limits the penalty if those assumptions are wrong. Subsequent increments are added only after certain hurdles or conditions are met.

- Variance reduction. The distribution of outcomes for staged entries is often tighter because the position grows only if conditions remain supportive. The trade-off is that some outsized wins are partially foregone when price moves favorably before additional increments fill.

- Execution quality. Splitting orders can reduce market impact costs in less liquid instruments. It can also provide more flexibility to use limit orders at desired prices rather than crossing the spread for the entire intended size.

- Gap and event risk control. When markets gap overnight or around events, a partially sized position can materially reduce adverse P&L swings relative to a fully sized position initiated immediately before the gap.

- Behavioral stability. Smaller early exposure can reduce the likelihood of premature exit prompted by discomfort, which indirectly supports adherence to a well-specified risk plan. This is a secondary benefit and does not replace quantitative risk limits.

Risk Budgeting and Position Sizing Math

Risk budgeting connects scaling decisions to a maximum loss threshold. Let R denote the intended maximum loss on the trade. The risk of a tranche is the size times the distance between its effective entry and the active stop. If tranches are added after price moves, the relevant distance for the new tranche is its own entry price minus the stop, not the first tranche’s entry. When the stop remains constant, each new tranche increases both exposure and total risk. When the stop is adjusted, the overall risk may stay constant or even decline, depending on the adjustment.

Consider a risk budget R of 1,000 currency units and an initial stop 2 units below the first entry.

- Single-shot entry. A single order of 500 units risks 500 times 2, or 1,000. If the stop is hit, the full budget is lost.

- Two-stage equal-size entry. Enter 250 units now. Risk is 250 times 2, or 500. If the second tranche of 250 is added only after a condition is satisfied and the stop remains unchanged, total risk becomes 250 times 2 plus 250 times the new distance to stop. If the second entry occurs 1 unit above the stop, the risk added is 250 times 1, or 250. Total risk becomes 750. A third tranche could be added later, up to the budget cap.

- Equal-risk increments. Each tranche is designed to add exactly 250 of risk. The size of each addition depends on the current stop distance. If the stop has been tightened, the tranche size can be larger while keeping incremental risk constant.

These examples illustrate the central control lever. The trader decides whether total risk ramps up gradually as evidence accumulates, or whether it stays fixed by tightening the stop as size increases. Either choice can be coherent if defined explicitly and implemented consistently.

Scaling In: Design Choices and Trade-offs

There are several ways to design entries. Each approach makes trade-offs between simplicity, execution cost, responsiveness to new information, and variance of outcomes.

Equal-Size Tranches

Equal-size tranches are easy to implement and audit. They allow partial participation while keeping the process transparent. The trade-off is that risk increases stepwise, which might push total risk above the intended budget if the stop is not adjusted. Clear rules are required for when to add and when to halt further additions. If conditions deteriorate quickly after the first tranche, the loss is smaller than under a full-size, immediate entry.

Equal-Risk Tranches

Equal-risk tranches keep incremental risk constant by scaling the size of each addition to the current stop distance. If volatility contracts or the stop is tightened based on predefined rules, the next tranche can be larger while adding the same incremental risk. This method aligns exposure growth with improvements in the measured risk landscape. The calculations are slightly more complex, but the risk accounting is clean.

Information-Conditioned Tranches

Another approach requires new, independent information before adding size. Examples include a reduction in realized volatility, the passing of a scheduled event that removes a source of uncertainty, or increased liquidity that reduces expected slippage. This design directly ties scaling to changes in the risk environment rather than to price alone. The trade-off is that fewer increments may be filled if conditions do not improve.

Common Pitfalls in Scaling In

- Confusing scaling with averaging down. Averaging down is adding to a losing position without a predefined risk cap, often to lower the average price. Scaling in is executed within a hard risk limit, with explicit tranche rules, and with a plan for not exceeding the budget.

- Martingale logic. Doubling size after losses to recover prior losses increases risk of ruin and violates stable risk budgeting. Scaling is not a recovery scheme.

- Over-fragmentation. Breaking entries into many small tranches can create excessive transaction costs and slippage that erode expectancy. Each tranche should be economically meaningful given costs.

- Ignoring correlation. Adding size across correlated instruments can unintentionally breach risk limits at the portfolio level even if each instrument is capped individually.

Scaling Out: Design Choices and Trade-offs

Scaling out reduces exposure after favorable movement or when uncertainty increases. The main benefit is variance control across the distribution of outcomes. It also provides flexibility if the thesis remains valid but conviction decreases.

Partial Profit Taking

One common design is to take a partial profit after a predefined multiple of initial risk. Suppose the initial tranche risk per unit is 2 currency units, and the price advances by 2 units. Exiting part of the position realizes a gain at a moment when the thesis has shown some confirmation. This reduces the capital at risk if the market reverses. The trade-off is theoretical maximum profit. If price continues to move favorably after the partial exit, the total gain is smaller than it would have been without scaling out. That is an intentional cost paid for variance reduction.

Risk Rebalancing

Scaling out can also be used to rebalance risk after volatility expands. If average true range or other volatility measures increase, the effective stop distance widens. Holding the same size now implies a larger dollar risk than initially planned. Reducing size restores the risk budget to its intended level. This use of scaling out keeps aggregate risk aligned with changing market conditions.

Trailing Stops and Residual Positions

Some risk plans keep a residual position with a trailing stop once partial profits have been realized. The stop mechanism is predefined and does not depend on discretionary judgments in the moment. The residual position maintains exposure to potential further gains while a portion of profits is protected. This structure creates a two-part payoff: realized gains that stabilize the equity curve and optionality on continued movement with declining risk capital.

Common Pitfalls in Scaling Out

- Inconsistent criteria. If exits occur for inconsistent reasons, the realized distribution of returns will be erratic. Predefining the triggers helps maintain coherence.

- Over-optimization. Tuning partial exit levels to past data can lead to fragile plans that underperform when conditions change.

- Premature liquidation. Reducing size too aggressively can remove the position before the main part of a move occurs, resulting in high turnover and muted returns relative to risk.

Illustrative Scenarios

Volatility Uncertainty at Entry

Imagine a market where recent volatility has been elevated and is beginning to contract, but the stability of that contraction is uncertain. A staged entry that begins with one third of the intended size can limit damage if volatility re-expands and the stop is hit. If, over the next sessions, volatility measures continue to decline and liquidity improves, a second and third tranche might be added. The total risk increases only as the environment becomes more stable, which can reduce the frequency of full-budget losses.

Liquidity Constraints

Large orders can move price in thin markets. Splitting entries over time with limit orders can achieve a better average execution price and lower realized slippage relative to a single large market order. Similarly, scaling out into strength or weakness can avoid signaling and reduce the market impact of a full liquidation. The quantitative benefit should be weighed against the risk of non-execution for some tranches.

Event-Driven Uncertainty

Scheduled events such as earnings releases or economic announcements can introduce gap risk. A position that is partially sized ahead of an event, with plans to add or reduce afterward, can materially change the distribution of potential outcomes. If the event passes without incident and liquidity normalizes, additional size can be considered within the pre-set risk budget. If the event introduces adverse information, the smaller pre-event exposure reduces capital loss.

Trend Continuation vs Mean Reversion Contexts

Scaling applies in both trend continuation and mean reversion contexts, although the mechanics differ. In a continuation context, increments may be added as price confirms the direction, often with tightening stops to keep total risk bounded. In a mean reversion context, increments might be added as price moves further from a reference level, but only within strict risk caps designed to avoid open-ended exposure. In both cases, the scaling rules must specify the maximum number of tranches, the maximum allowable risk, and conditions for halting further additions.

Risk of Ruin, Survivability, and Equity Curve Stability

Long-term survivability depends less on extracting the theoretical maximum from each opportunity and more on avoiding catastrophic losses that permanently impair capital. Scaling contributes to survivability in three ways.

- It reduces the frequency and magnitude of early, full-size losses by keeping initial exposure small relative to the final intended size.

- It allows evidence to accumulate before full risk is deployed, which can improve the match between conviction and exposure without relying on prediction.

- It facilitates disciplined profit realization and risk rebalancing, which can make the equity curve smoother and reduce drawdown depth and duration.

These benefits are probabilistic, not guaranteed. There are periods when scaling leaves gains on the table compared with an immediate full-size entry that benefits from a strong, one-directional move. The consistent application of scaling principles is justified by the role of risk control in long-horizon capital preservation rather than by any single-trade outcome.

Practical Implementation Considerations

Documentation and Precommitment

Clear documentation prevents ambiguity. A robust plan specifies the maximum number of tranches, size or risk per tranche, activation criteria, maximum total size, stop management logic, and conditions under which additions are halted. The same applies to scaling out: levels or conditions for partial exits, size of each reduction, and the final exit rule. Precommitment reduces the chance of discretionary decisions that expand risk beyond the budget in stressful conditions.

Transaction Costs and Slippage

Scaling increases the number of tickets traded. The economic value of variance reduction must exceed the cost of added commissions, fees, and slippage. The optimal number of tranches is rarely the maximum possible. It is the number at which marginal variance reduction approximately equals marginal cost. This balance varies by instrument liquidity, typical spread, and volatility regime.

Stop Management

Stop logic interacts with scaling. If the stop is fixed while size increases, total risk rises with each addition. If the stop is tightened as size increases, total risk can remain near the cap, but stop movement must be rule-based to avoid random whipsaw. Some plans use a two-stop approach: an initial protective stop to cap loss and a trailing stop that engages only after partial profits are taken. Regardless of method, the plan should account for gap risk, which may cause slippage beyond the stop price.

Portfolio-Level Effects

Scaling decisions should be evaluated at the portfolio level. Adding to several positions at once can concentrate exposure if their returns are correlated. Likewise, scaling out across positions can simultaneously reduce portfolio variance. Risk budgeting tools that aggregate exposures by factor or asset class can prevent unintentional clustering that defeats the purpose of scaling.

Data and Feedback

Trade logs that record each tranche, its rationale, and the resulting risk at the time of execution provide the data needed to evaluate whether scaling improves outcomes. Useful metrics include average adverse excursion, average favorable excursion, realized slippage per tranche, and the proportion of planned tranches that typically fill. Over time, these statistics help calibrate tranche size and activation thresholds.

Common Misconceptions

- Scaling guarantees better entries or exits. It does not. Scaling manages risk and variance. Price may run immediately in a favorable direction and never provide the opportunity to add, which can result in smaller gains than a full-size entry would have produced.

- Scaling is inherently conservative. Scaling can also increase total risk if additions are made while stops are widened without a clear rationale. The method is only as conservative as the risk rules that govern it.

- Scaling is a substitute for a clear thesis. Without defined invalidation points and risk limits, scaling can devolve into random size changes that obscure performance analysis.

- Partial profits always improve results. They often reduce variance but can lower long-run expectancy if taken too early or too frequently relative to the behavior of the instrument.

Worked Example: Comparing Single-Shot and Staged Paths

Assume the following. The instrument trades near 100. The initial stop is at 97. The risk budget is 1,500 currency units. Transaction costs per trade are modest. Two entry methods are compared.

Method A, single-shot. Enter 500 units at 100. Total risk is 500 times 3, or 1,500. If the price immediately reverses to 97, the loss equals the budget. If price rises to 106 before any exit, mark-to-market profit is 500 times 6, or 3,000.

Method B, three tranches. Enter 200 units at 100 with stop 97. Risk is 200 times 3, or 600. If price rises to 101 without increasing volatility, add 200 units at 101 with the stop unchanged. This adds 200 times 4, or 800, raising total risk to 1,400. If price rises to 103 and volatility declines, add 100 units at 103 and tighten the stop to 100 based on predefined criteria. The final risk becomes 200 times 0 plus 200 times 1 plus 100 times 3, which equals 0 plus 200 plus 300, or 500. If price falls to 100 after the third tranche, the mark-to-market drawdown is limited by the updated stop plan. If price rises to 106, the profit is 200 times 6 plus 200 times 5 plus 100 times 3, which equals 1,200 plus 1,000 plus 300, or 2,500.

The staged method reduces worst-case loss early in the trade and ends with a smaller profit than the single-shot method in this particular path. Over many paths, the staged approach may produce smoother equity with fewer large early losses, while giving up some tail gains when price runs immediately. Whether that trade-off is suitable depends on the role of variance control in the overall plan and on the characteristics of the traded instruments.

Integrating Scaling into a Coherent Risk Plan

Scaling is part of an integrated risk framework that includes capital allocation limits, stop logic, execution protocols, and portfolio diversification. To function properly, it must be consistent with the following.

- Capital allocation. Define maximum capital and risk per position and per portfolio.

- Invalidation criteria. Establish clear levels or conditions that render the thesis invalid. Scaling should not expand exposure if invalidation is near.

- Execution method. Specify order types for each tranche and the conditions under which to use them.

- Review cadence. Periodically evaluate whether scaling parameters remain fit for the prevailing volatility and liquidity regimes.

Final Thoughts on Survivability

The primary objective of scaling in and scaling out is to shape the risk taken on the way into and out of exposure. It helps manage the fact that information arrives over time and that markets are noisy, discontinuous, and costly to trade. By allocating risk gradually, realizing profits methodically, and keeping total exposure within explicit caps, scaling can contribute to preserving trading capital through changing market conditions. The technique does not replace the need for a sound thesis, disciplined stops, or careful portfolio construction. It complements them by acknowledging that path matters as much as endpoint in the real world.

Key Takeaways

- Scaling in and scaling out are position sizing techniques that stage entries and exits to control risk under uncertainty.

- Proper scaling ties every tranche to an explicit risk budget, with clear rules for when to add, reduce, or halt changes in size.

- Variance reduction and improved execution quality are typical benefits, offset by the cost of leaving some tail gains unrealized.

- Common pitfalls include averaging down without limits, martingale logic, over-fragmentation that inflates costs, and ignoring portfolio-level correlation.

- Scaling supports long-term survivability by reducing the frequency of large early losses and stabilizing the equity curve across varied market conditions.