Position count is easy to see and simple to report. Exposure is harder to measure but far more important. Confusing the two invites concentration, clustered losses, and avoidable drawdowns. In risk management, survivability depends on how underlying risks combine, not on how many line items appear in a blotter. This article clarifies the distinction between exposure and position count, explains why the difference matters for protecting capital over long horizons, and surveys practical ways to evaluate concentration when correlations shift.

Position Count Is Not Diversification

Position count is the number of distinct instruments held at a point in time. A portfolio might contain 40 stocks, 12 exchange-traded funds, and 8 options contracts. The count looks large, and it can create a sense of safety. Yet many of those instruments may share the same underlying drivers. If that is the case, the portfolio is not diversified in any meaningful sense. It is a collection of related bets that can move together under stress.

Exposure, by contrast, is the portfolio’s sensitivity to sources of risk. A portfolio has exposure to broad equity market beta, to size and value factors, to industry or regional developments, to rates, credit, and inflation, to currency moves, and to volatility. Each position contributes to one or more of those exposures, and the way exposures interact depends on correlation. Proper risk control evaluates the exposures that remain after aggregation, not the number of names on the page.

Defining Exposure

Directional and Notional Exposure

Directional exposure refers to how a portfolio’s value changes when an underlying market moves. Dollar notional, or the face value tied to the market move, is a starting point. If a portfolio holds 100,000 dollars of a broad equity index and hedges 60,000 dollars with a short position in a highly correlated index future, the gross exposure is 160,000 dollars and the net notional exposure is 40,000 dollars. The same arithmetic applies in credit, commodities, and currencies. Notional is simple and often useful, but it can be misleading when different instruments have distinct volatilities or betas relative to a common benchmark.

Volatility- and Beta-Adjusted Exposure

Volatility-adjusted exposure scales positions by their typical variability. A 20,000 dollar position in a low-volatility instrument may carry less risk than a 10,000 dollar position in a high-volatility instrument. Beta-adjusted exposure measures sensitivity to a broad factor, such as equity market returns. For example, a basket of defensive stocks might have a beta of 0.6 to the market, while a cyclical basket might have a beta of 1.3. Two baskets with similar notionals can have very different beta-adjusted exposures.

Factor, Sector, and Thematic Exposure

Factor exposure attributes risk to systematic drivers that cut across securities. Common equity factors include value, size, momentum, quality, and low volatility. Sector exposure groups securities by industry classification. Thematic exposure focuses on shared narratives or macro sensitivities, such as energy transition, artificial intelligence infrastructure, or consumer discretionary spending. Different classification schemes can be used together to form an exposure map that is more informative than the raw position count.

Derivative Greeks and Nonlinear Exposure

Options and other derivatives add nonlinear exposures. Delta captures sensitivity to the underlying price, gamma captures how delta changes, vega captures sensitivity to implied volatility, theta captures time decay, and rho captures sensitivity to interest rates. A portfolio can have very modest delta exposure but large vega exposure, which will behave differently across regimes. Counting contracts does not capture this risk. Exposure requires mapping positions into common risk units.

Gross vs Net Exposure

Gross exposure sums the absolute value of long and short positions. Net exposure is the difference between longs and shorts. Net exposure can be low while gross exposure is high. In market-neutral strategies the net market beta may be close to zero, yet factor exposures, idiosyncratic concentration, liquidity exposure, and trade crowding can remain high. Gross and net provide useful context, but they are not substitutes for a full exposure profile.

Correlation and Effective Diversification

Correlation describes the extent to which returns move together. Diversification reduces risk when positions are imperfectly correlated. The portfolio’s variance is determined by position volatilities and by correlations across them. Two positions with low correlation can offset each other’s variability. Ten highly correlated positions behave like one large position. The effective number of independent bets is often far smaller than the raw count when correlations cluster around one in stress conditions.

Why the Distinction Matters for Risk Control

Long-term survivability depends on avoiding large drawdowns that impair capital and reduce optionality. Concentration in exposures, not only in names, is the driver of many damaging losses. When a single theme dominates, bad outcomes tend to arrive in clusters. The portfolio drops at the same time margin requirements rise, liquidity thins, and correlations converge. Position count will not mitigate that sequence if the exposures are aligned in the same direction.

Several mechanisms amplify this dynamic. First, correlations are state dependent. Relationships that look modest in calm periods often increase when volatility rises. Second, leverage transforms small correlation errors into large losses. Third, liquidity evaporates quickly when many participants hold similar exposures. Finally, funding risk interacts with market risk. If the portfolio’s exposure requires substantial financing, mark-to-market losses can trigger forced reductions at unfavorable prices. Managing exposure, not count, addresses these compounding risks.

Measuring Exposure in Practice

The most useful measurements translate heterogeneous positions into a common set of risk factors. Methods vary by asset class and data availability, but the underlying idea is consistent. Identify the main drivers, estimate how each position responds to those drivers, aggregate at the portfolio level, and consider how the drivers co-move. Several complementary lenses are commonly used.

Notional and Beta Weighting

Start with gross and net notional by asset class and sector. Then estimate betas to a broad benchmark for each equity position or basket, and to relevant macro factors for rates, credit, currencies, or commodities. Beta weighting translates the portfolio into a standardized unit, such as market beta dollars. This reveals when a collection of small names collectively embeds a large directional tilt.

Factor Models

Multi-factor models attribute each position’s return to a set of systematic factors plus idiosyncratic noise. Examples include style factors in equities, term and curve factors in rates, or carry and momentum in currencies. Summing factor exposures across positions produces a factor-level picture that cuts through name-level complexity. A portfolio can have neutral sector weights but substantial exposure to the momentum factor. That condition will dominate behavior when momentum regimes shift.

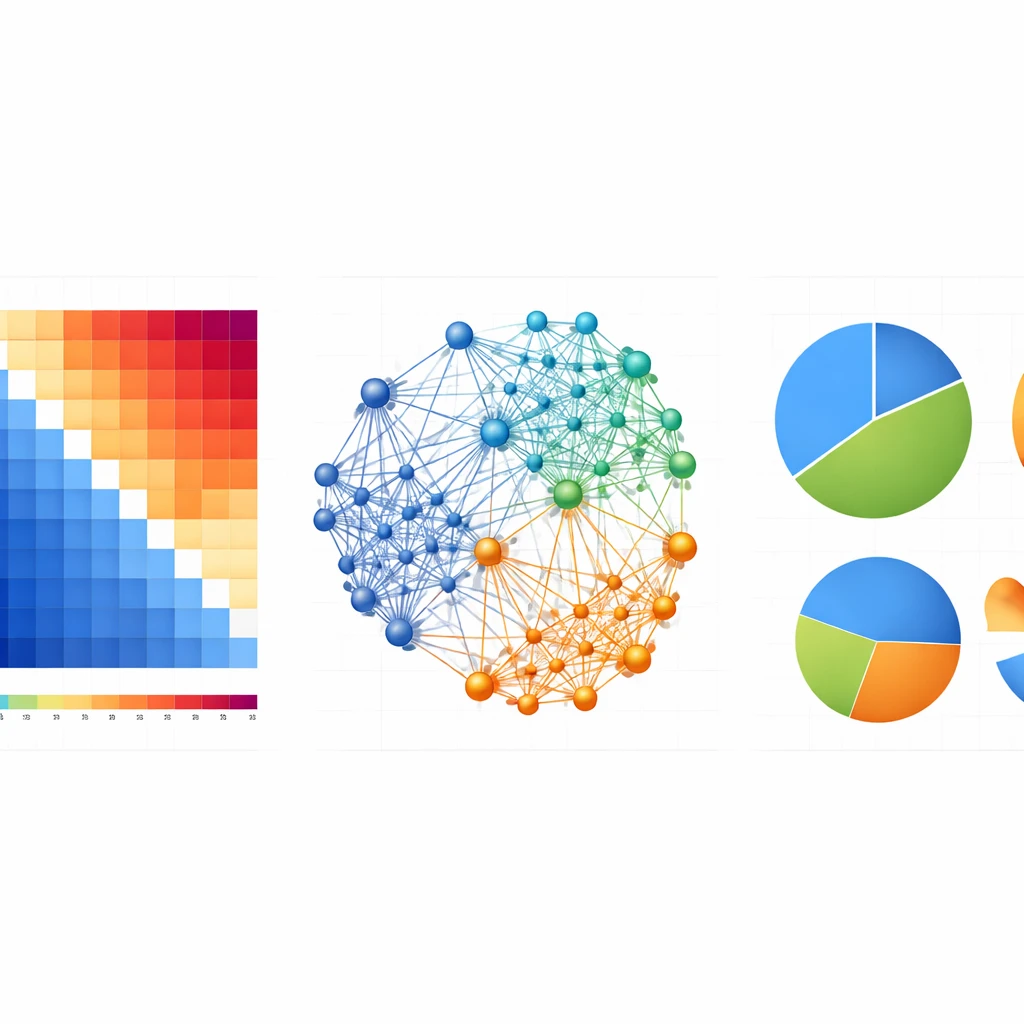

Correlation Matrices and Clustering

Constructing a correlation matrix across positions or factor-mimicking portfolios allows for an assessment of co-movement. Hierarchical clustering or simple grouping by high pairwise correlation can highlight latent themes. It is common to observe that several industries, regions, and instruments line up on a single macro dimension, such as the global growth cycle or real rates. Clustering translates a long list into a small set of exposure blocks.

Portfolio Variance and Contribution to Risk

A standard approach is to compute portfolio variance from estimated volatilities and correlations, then decompose the result into contributions by position, sector, or factor. Contribution to risk differs from contribution to weight. A small weight in a volatile and highly correlated cluster can contribute disproportionately to total risk. This decomposition is often the most direct way to see concentration that position count obscures.

Scenario and Stress Exposures

Beyond average covariances, scenario analysis asks what happens under targeted shocks. Examples include a parallel shift in rates, a credit spread widening, a jump in oil prices, or a sharp decline in a regional equity index. These scenarios express exposure in intuitive terms. They also help address correlation instability by focusing on coherent stories rather than solely on historical averages.

Illustrative Real-World Patterns

Many Names, One Theme

Suppose a portfolio holds 15 individual technology stocks, a technology sector ETF, and a semiconductor ETF. The position count is high. The factor map shows heavy exposure to growth and momentum, and the correlation matrix reveals a strong common component linked to the sector. Under a growth scare, all positions tend to decline at the same time. The true diversification is limited because the exposure is concentrated in one theme.

Few Names, Diverse Drivers

Contrast that with a portfolio of three positions that are carefully chosen to reflect different risks. One is linked mostly to interest rate duration, another to energy supply dynamics, and a third to local consumer demand in a different currency. The position count is small, yet the exposures are genuinely distinct. Correlations among the drivers are low in most environments. The portfolio can experience more stable aggregate risk than the first case despite fewer line items.

Overlapping Holdings Through Funds

Funds and indices introduce hidden overlap. An investor might hold several ETFs with different labels that track the same benchmark constituents. Alternatively, two broad funds can share large weights in the same few mega-cap companies. The position count seems to rise when adding funds, but the exposure may barely change. Examining look-through holdings or reported top weights often reveals that the incremental exposure is small and highly correlated with what is already held.

Options With Shared Greeks

Consider a collection of short-dated options written on several stocks within a cyclical industry. The deltas could net to a modest directional exposure if strikes and sides partially offset, yet the portfolio can carry substantial vega and gamma exposure that spikes when volatility rises or when prices gap. The shared Greek profile means the positions respond together to implied volatility changes. The count is not protective because the dominant exposure is the same.

Market-Neutral but Factor-Exposed

A long-short equity book might target zero market beta by matching long and short betas. Despite the low net exposure, the book can be tilted toward a single factor such as small size or momentum. If the factor reverses, the long and short sides can lose together. The result is a drawdown that appears puzzling when viewed through net exposure alone, but is intuitive in the factor exposure view.

Currency and Carry Clustering

Several currency pairs can share the same driver, such as a global appetite for carry or a shift in commodity prices. A set of apparently diverse pairs can move together when a risk-off episode causes carry trades to unwind. Counting the pairs gives a false sense of independence. The exposure lens shows that the positions are tied to the same macro condition.

Common Misconceptions and Pitfalls

Several recurring misconceptions blur the distinction between exposure and position count.

- More positions mean more diversification. This is only true when exposures are sufficiently independent. When positions load on the same factor or theme, the effective number of bets remains low.

- Low net exposure means low risk. Netting longs against shorts can hide large gross positions and concentrated factor or vega exposure. Losses can arise from the common component not captured by the net metric.

- Hedges eliminate risk. A hedge reduces a targeted exposure but can leave others untouched. Basis risk, liquidity risk, and the possibility that correlations change can undermine a hedge precisely when it is most needed.

- Correlations are stable. Historical correlations are averages. They vary across regimes and often rise in selloffs. A portfolio that appears diversified on average can behave like a single position in stress.

- Small positions cannot matter. A small weight in a high-volatility, high-correlation cluster can contribute meaningfully to risk. Concentration should be evaluated through contribution to risk, not weight alone.

Managing Exposure Without Relying on Count

Risk processes that focus on exposure rather than count share several traits. They map positions to common risk drivers, compare exposures against concentration thresholds, and monitor how those exposures evolve. Several techniques are widely used across professional settings.

Volatility scaling normalizes positions so that each contributes a comparable amount of variability under typical conditions. Contribution to risk limits set maximum shares of total portfolio variance that can come from any single position, sector, or factor. Sector and theme caps prevent one narrative from dominating the book. Liquidity-aware sizing recognizes that positions with thin markets or wide spreads can produce larger realized losses than their ex-ante variance suggests. Scenario testing examines how the portfolio behaves under defined shocks, helping to detect concentrations that standard covariance estimates miss.

Correlation-aware rebalancing focuses on clusters. When multiple positions are highly correlated, the combined exposure is treated as one block for sizing and monitoring purposes. This can be done informally by grouping related names, or more formally through clustering on the correlation matrix. The key is to avoid counting several versions of the same risk as separate diversifiers.

Transparency across layers of instruments also matters. Options are translated into Greeks, futures into standardized contract value and volatility equivalents, and funds into look-through holdings. Without this translation, the exposure map is incomplete and the position count gives a distorted picture of concentration.

Interpreting Correlation and Regime Shifts

Correlation is a moving target. Short windows can be noisy and dominated by event-specific effects. Long windows can blend together different regimes and understate the risk of sharp correlation increases in stress. A practical approach is to examine several horizons, compare calm and volatile periods, and give extra weight to conditions that resemble current or plausible future environments. Conditional correlations, estimated during episodes of elevated volatility, can offer a more conservative view of diversification.

Asymmetry is common. Correlations among risky assets tend to rise in downturns when funding constraints and risk aversion bind. Portfolios built on the assumption of stable low correlations can suffer larger drawdowns than expected when this asymmetry appears. Scenario analysis complements statistical estimates by asking whether a shared catalyst could plausibly move many positions together. Examples include policy surprises, liquidity withdrawals, or concentrated earnings disappointments within a sector.

Exposure, Leverage, and Liquidity

Leverage magnifies exposure. The same fractional move in the underlying creates a larger change in equity when financing is involved. Correlation errors are costlier under leverage, and margin requirements can rise when volatility picks up. Liquidity interacts with exposure as well. A portfolio concentrated in thinly traded instruments can experience larger slippage and gaps, effectively increasing realized exposure relative to measured exposure. During stress, the act of reducing a position can move the market enough to erode the intended benefit.

Funding risk is an exposure of its own. Portfolios that rely on short-term financing can be forced to reduce positions at unfavorable times, even when the long-run outlook is unchanged. Concentrating exposure in instruments with similar funding terms or collateral requirements compounds this vulnerability. Diversifying across funding sources and recognizing the liquidity profile of each position help align measured exposure with realized behavior under pressure.

From Numbers to Judgment

Quantitative exposure metrics are necessary but not sufficient. Judgment matters in deciding which drivers are most relevant and which correlations are likely to change. A factor model can understate risk if the true driver is a theme not captured by the factors. A scenario can be incomplete if it ignores important second-order effects such as supply chain linkages or regulatory responses. Effective risk control blends measured exposure with qualitative understanding of how the world is connected.

Documentation supports this blend. Recording the intended drivers for each position, along with the expected correlations, creates a baseline for evaluation. When markets evolve, differences between expectation and reality are easier to diagnose. Over time, this habit builds a more accurate map of exposures and a more resilient portfolio construction process.

Applications Across Asset Classes

The basic ideas apply in equities, fixed income, commodities, and currencies alike. In equities, overlapping sector bets and common style loads dominate. In fixed income, duration, curve shape, credit spread, and inflation sensitivity are the key exposures, and correlations change with policy regimes. In commodities, supply disruptions and inventory cycles create clustering across apparently unrelated markets that share logistics or energy inputs. In currencies, carry, value, and risk sentiment drivers often align positions that look different by pair but depend on the same global conditions. Recognizing these patterns prevents the overcounting of diversification and improves control of drawdown risk.

Protecting Capital and Survivability

Capital is protected when adverse outcomes are bounded and when losses do not arrive all at once. Exposure analysis supports this by identifying where the same catalyst can affect many positions simultaneously. Survivability improves when the portfolio can absorb unexpected correlation changes, adapt to regime shifts, and maintain flexibility rather than face forced reductions. Controlling exposure rather than counting positions aligns the risk process with these objectives.

Effective exposure management is not a call for minimalism or for any specific portfolio architecture. It is a call for clarity. The risks that matter are the ones that move the portfolio together, especially in stress. Knowing those links, and measuring them in ways that remain meaningful across environments, is the difference between a list of positions and a risk-managed portfolio.

Key Takeaways

- Position count measures how many instruments are held, while exposure measures how those instruments respond to shared risk drivers.

- Diversification depends on correlation and factor loads, not on the number of names. Many positions can still represent one exposure.

- Useful exposure views include beta and volatility scaling, factor attribution, correlation clustering, contribution to risk, and scenario analysis.

- Correlations are regime dependent and often rise in stress, so average historical relationships can overstate diversification.

- Protecting capital and long-term survivability relies on identifying and managing concentrated exposures rather than adding more line items.