Correlation across asset classes is a central concept in risk management because it governs how losses and gains can cluster when markets move together. Assets that appear different by label can still be driven by the same underlying forces and, as a result, can move in tandem during important periods. Understanding these linkages helps reduce concentration, control drawdown paths, and improve the odds of long-term survivability in the presence of uncertainty.

What Correlation Across Asset Classes Means

Correlation is a statistical summary of how two return series move relative to each other over time. The commonly used Pearson correlation coefficient ranges from minus one to plus one. A value near plus one indicates that two assets tend to rise and fall together. A value near minus one indicates they frequently move in opposite directions. A value near zero indicates weak or no linear co-movement.

In cross-asset contexts, correlation is applied to returns for equities, government bonds, credit, commodities, currencies, real estate, and sometimes newer categories such as digital assets. The question is not whether these assets are identical, but whether their returns respond to shared drivers like growth expectations, inflation, policy rates, liquidity conditions, and global risk appetite.

The essential point is that correlations are not fixed constants. They change with the state of the world, the time horizon used to compute them, and the sample window. During a market stress episode, correlations that were modest in quiet times can shift toward higher positive values, leading to simultaneous losses across positions that might have been considered diversified.

Why Correlation Is Critical to Risk Control

Risk is not only about the volatility of individual positions. It is also about how positions interact in a portfolio. If several positions share the same driver, their losses can cluster. Clustering can magnify drawdowns, accelerate margin usage, and force position reductions at unfavorable prices. Survivability depends on limiting the probability and severity of such clustered losses.

Effective correlation awareness supports several risk control aims:

- It reduces hidden concentration by revealing when different tickers are actually the same trade in disguise.

- It improves capital efficiency by aligning risk with the number of independent sources of return rather than the number of line items.

- It encourages monitoring of regime shifts so that historical diversification assumptions are not carried forward mechanically.

These benefits occur without relying on forecasts of price direction. The focus is on the structure of co-movement, not on prediction of specific market outcomes.

How Correlation Is Measured in Practice

Practitioners typically compute correlations on returns that are cleaned and aligned in time. Several details matter for robust estimates:

Frequency and horizon

Correlation depends on the horizon. Daily correlations can differ from monthly or intraday values. For example, short-horizon correlations often reflect liquidity flows and risk-on risk-off behavior. Longer horizons may capture macroeconomic trends and policy shifts. It is common to examine multiple horizons and to avoid mixing frequencies when interpreting relationships.

Return definitions

Use returns rather than price levels. For equities, log or simple returns are common. For rates, use returns that reflect price sensitivity, such as changes in yield or DV01-normalized P and L. For commodities and currencies, rollover and carry effects can affect measured returns. The goal is to ensure that the numbers represent comparable risk changes.

Rolling windows

Correlations are frequently computed over rolling windows such as 60 trading days or 24 months. Short windows adapt quickly but can be noisy. Long windows are more stable but can conceal recent regime changes. Many teams examine a set of windows to view both short-term and structural co-movement.

Nonlinearity and tail behavior

Pearson correlation captures linear co-movement around the average. It does not fully describe relationships that are nonlinear or that strengthen in the tails. Some practitioners also look at rank correlations or conditional correlations during stress months. The goal is to understand whether diversification tends to fail when it is most needed.

Sampling error and stability

Correlation estimates are subject to error. Small samples or volatile regimes can produce unstable values. This is one reason to supplement point estimates with qualitative knowledge of macro drivers and with stress tests that impose hypothetical shocks across assets.

Systematic Drivers That Link Asset Classes

Many cross-asset correlations can be understood through a small set of underlying forces:

- Growth expectations: Equities, cyclical commodities, and credit often benefit from improving growth. Emerging market currencies tied to export cycles can move similarly.

- Inflation and real rates: Inflation changes the value of nominal bonds, real yields, and inflation-sensitive assets such as commodities and some equities. When inflation surprises rise, nominal bonds can fall while commodities rise, altering correlations.

- Monetary policy and liquidity: Shifts in policy rates and balance sheet policies affect funding costs, valuations, and global risk appetite. Liquidity shocks can cause seemingly unrelated assets to move together.

- Risk sentiment: Assets tied to carry or volatility premia tend to perform well during stable conditions and poorly during risk aversion. This can link positions across equities, credit, and currency carry.

- The global dollar cycle: The strength of the dollar influences commodities priced in dollars, external financing conditions for many economies, and cross-border flows. Dollar swings can align movements across emerging market assets and commodities.

The presence of these shared drivers helps explain why diversification by label does not guarantee diversification by outcome.

Real-World Scenarios Illustrating Cross-Asset Correlation

Equities, credit, and cyclicals

Consider a portfolio that includes a broad equity index future, an investment grade credit fund, and a basket of cyclical commodity producers. While these instruments belong to different asset classes, their performance can be tied to growth and corporate cash flows. During a growth scare, credit spreads can widen, equities can sell off, and cyclical producers can underperform. The loss pattern reflects exposure to a common growth factor rather than three independent sources of risk.

Emerging market carry and volatility exposure

An investor might hold a positive carry position in several high-yielding currencies and also a position that benefits from stable equity volatility. These appear to be different strategies, but both can be sensitive to risk sentiment and funding conditions. A rise in global risk aversion can cause a sell-off in high beta currencies and a jump in equity volatility, producing losses that cluster.

Commodities, transportation, and inflation surprises

Suppose a book includes crude oil exposure and a position in airline equities. Oil prices and airline margins often move in opposite directions. During an inflation shock, however, the relationship can change. If inflation leads to higher policy rates and weaker growth expectations, both assets can fall at the same time because the demand outlook deteriorates and financing costs rise. A correlation that appears negative in ordinary times can become positive in stress periods.

Gold and government bonds

Gold and long-duration government bonds have sometimes moved together when disinflation and falling real yields supported both. In periods of inflation surprise or concerns about fiscal sustainability, this relationship can weaken or reverse. A portfolio holding both may find that diversification benefits shrink when inflation becomes the dominant driver.

Dollar strength and global assets

During episodes of broad dollar strength, commodity prices can decline and emerging market assets can face pressure. Portfolios with exposure to commodities, emerging market equities, and local currency bonds can experience losses at the same time because dollar appreciation tightens global financial conditions and changes purchasing power dynamics.

From Notional Holdings to Risk Exposure

Labeling positions by notional size often masks their true contribution to aggregate risk. Cross-asset risk control depends on translating holdings into comparable risk units. Several steps are common in practice, even when implemented with different tools:

- Normalize by volatility: Express each position in volatility terms so that equal-sized risk units make a comparable contribution to day-to-day variability. This helps reveal when a small notional position is in fact the dominant source of risk.

- Consider sensitivity measures: For rates, DV01 summarizes price change per basis point move. For options, delta and vega describe sensitivity to underlying price and volatility. For credit, spread duration and default risk matter. These measures allow mapping to common factors.

- Aggregate by factor: Group exposures by drivers such as growth, inflation, real rates, dollar, and liquidity. This reveals when different instruments load on the same factor, even if they sit in different asset buckets.

- Recognize basis risk: A proxy hedge can diverge from the targeted exposure. For example, using a broad commodity index to offset a single commodity position introduces basis risk that can amplify rather than reduce concentration.

The objective is clarity about where the portfolio takes its risk. Common factor mapping often shows that a portfolio with many line items actually rests on a few correlated bets.

Correlation Is Regime Dependent

Cross-asset correlations tend to change as macro conditions evolve. Several patterns recur in historical data:

- Flight-to-quality episodes: Equities and credit tend to fall together while high-quality government bonds may rise. Correlations within risky assets increase, and diversification across them weakens.

- Inflation-driven sell-offs: Inflation surprises can drive bonds and some equities lower together, reducing the historical diversification that bonds provided in disinflationary regimes.

- Liquidity shocks: When funding tightens, investors reduce exposures broadly. Assets with different fundamental drivers can still move together because liquidity becomes the dominant force.

Because regimes shift, static correlation matrices from long samples can be misleading. Many risk teams supplement long-term averages with conditional or rolling estimates and apply judgment about the current state.

Common Misconceptions and Pitfalls

Several recurring mistakes affect how correlation is used in risk management:

- Diversification by label: Holding instruments from different asset classes does not guarantee independent outcomes. The drivers may be the same.

- Using prices instead of returns: Price levels often produce spurious correlations. Analysis should focus on properly defined returns for each asset type.

- Frequency mismatches: Mixing daily and monthly returns in the same correlation analysis produces misleading results. Keep horizons consistent when interpreting co-movement.

- Treating correlation as stable: Assuming last year’s correlation will hold in the next stress period underestimates risk. Correlation often increases when volatility rises.

- Ignoring tail dependence: Assets with modest average correlation can still crash together. Conditional analysis helps reveal this vulnerability.

- Overreliance on a single metric: Pearson correlation is useful but incomplete. Rank-based measures, stress tests, and factor models provide additional perspectives.

- Proxy hedging without calibration: Offsetting a position with a loosely related instrument can add basis risk. Calibration to factor sensitivities is required to understand residual exposure.

- Currency base omissions: A portfolio measured in a home currency can have unintended correlation with the exchange rate. For example, foreign equity exposure is partly a currency bet unless hedged, and the currency piece can correlate with other assets.

Interpreting Correlation in a Portfolio Context

Portfolio-level risk emerges from the interaction of volatilities and correlations. A few practical interpretations help connect the statistic to portfolio behavior:

- Clustering of losses: Positive correlation among large positions increases the chance that multiple holdings lose value at the same time. This can produce drawdowns larger than those implied by any one position.

- Number of independent bets: The more positions load on the same driver, the fewer independent sources of risk exist. Measures such as the effective number of bets or diversification ratio translate a correlation matrix into a count of independent components.

- Marginal and component risk: The risk contribution of a position depends on both its own volatility and its correlation with the rest of the portfolio. A modestly volatile position can still be a large risk contributor if it is strongly correlated with the current portfolio direction.

- Hedging and residual risk: A hedge reduces risk to the extent that it is negatively correlated with the exposure being hedged and appropriately scaled. Hedging with an imperfectly correlated instrument leaves residual risk that can vary through time.

Stress Testing and Conditional Correlation

Stress testing complements correlation analysis by asking how a portfolio might behave under specific shocks. The key purpose is to examine whether exposures that appear diversified under average conditions would in fact move together under stress. Common scenarios include inflation surprises, policy shifts, growth contractions, commodity supply shocks, and dollar funding squeezes. In each case the relevant question is which assets would likely respond to the same driver and whether their correlation would rise conditionally on the shock.

Conditional analysis avoids relying solely on historical averages. A portfolio that looks balanced in a long-term correlation matrix can still be exposed to a concentrated set of stress outcomes. Scenario analysis helps illuminate those cases before they materialize.

Linking Correlation Awareness to Survivability

Long-term survivability depends on avoiding sequences of losses that are both large and rapid. Correlation across asset classes plays a direct role in shaping these sequences. When correlation rises, the distribution of portfolio losses becomes more fat-tailed because many components can draw down together. This has implications for margin usage, funding availability, and the ability to wait for mean reversion.

In practical terms, correlation awareness supports survivability through three channels. First, it reduces exposure to the same underlying driver being expressed repeatedly across instruments. Second, it helps anticipate when historical diversification might fade, such as during inflation shocks or liquidity crunches. Third, it supports the design of stress tests that probe for conditional clustering and wrong-way risk.

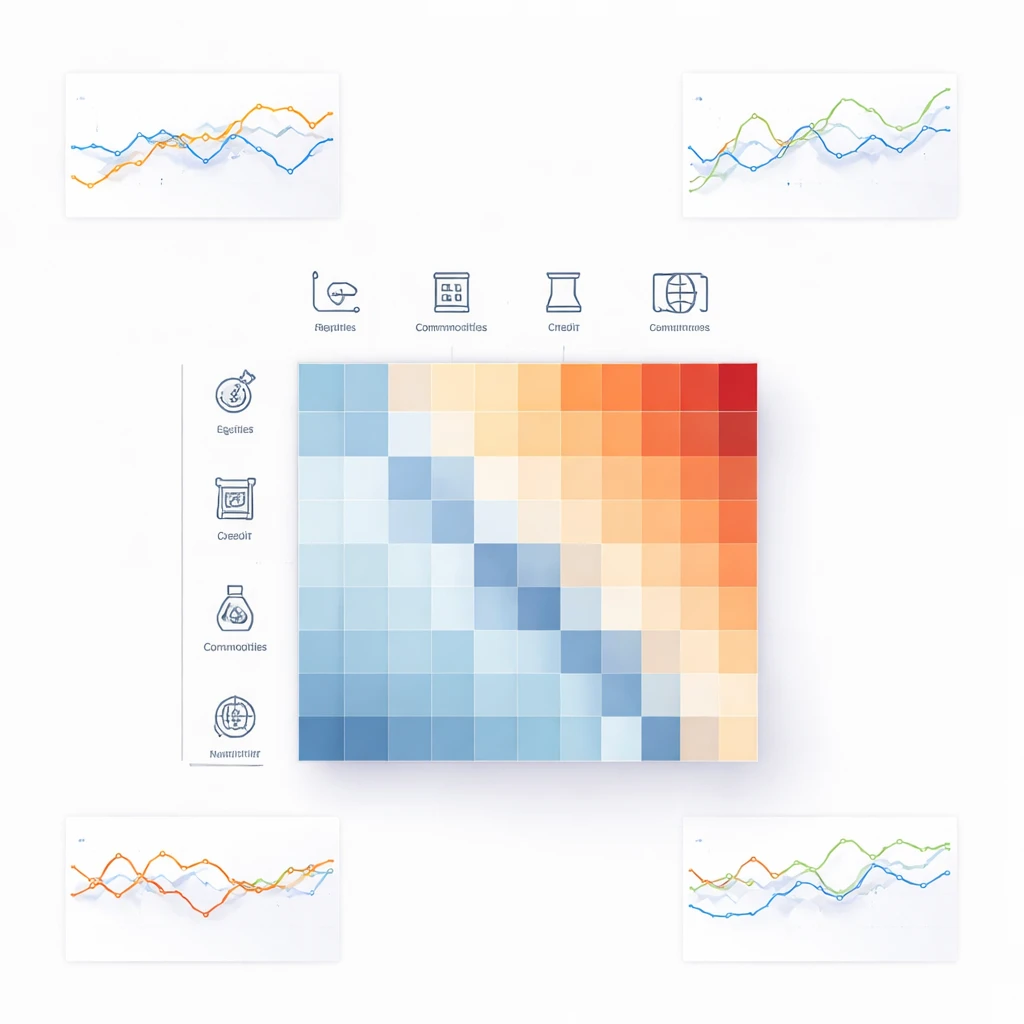

Illustrative Workflow for Monitoring Cross-Asset Correlation

A common monitoring workflow includes the following elements. The sequence is descriptive and does not prescribe specific actions.

- Define a set of representative instruments across major asset classes that reflect current holdings and plausible substitutes.

- Measure returns at consistent frequencies and align time stamps to avoid stale values and mismatches.

- Compute rolling correlation matrices over several windows to observe short-term and medium-term behavior.

- Map instruments to a small set of macro drivers and estimate factor loadings using regressions or principal components to identify concentration.

- Run stress scenarios tied to inflation, growth, policy, liquidity, and the dollar to evaluate conditional co-movement.

- Track changes in marginal and component risk contributions through time to detect hidden build-ups in correlated exposures.

The outcome of this workflow is an evolving view of where risks cluster. The same approach scales from a few positions to a more complex multi-asset portfolio.

Special Considerations by Asset Class

Different markets carry distinct conventions for measuring and interpreting exposure. These differences affect how cross-asset correlation is translated to portfolio risk.

- Rates and government bonds: Duration and DV01 matter. Two bond positions can have similar notional sizes but very different risk contributions because of duration. Their correlation with equities can flip with inflation regimes.

- Credit: Spread duration and default risk are sensitive to growth and funding conditions. Correlation with equities often rises during stress because both reflect corporate health and risk appetite.

- Commodities: Idiosyncratic supply shocks can decouple individual commodities from broad indices. Correlation with equities can vary with the source of the shock. Energy prices may correlate with inflation and real income expectations in different ways across regimes.

- Currencies: Bilateral exchange rates embed both countries’ fundamentals and the global funding cycle. The dollar often acts as a cross-asset driver. Currency exposures can therefore alter the correlation structure of a portfolio more than their notional sizes suggest.

- Equities: Sector composition matters. Commodity producers, financials, and defensives respond to different macro drivers. A cross-asset analysis benefits from understanding equity sector linkages to rates, credit, and commodities.

What Correlation Does Not Tell You

Correlation does not measure causation. Two assets can be correlated because of a third driver or because of overlapping investor bases. Also, a low average correlation does not guarantee that losses will not cluster in a crisis. Correlation is a summary statistic, not a structural explanation. It should be interpreted alongside volatility, liquidity measures, and scenario analysis.

Correlation also does not capture path dependency. An asset that trades quietly most of the time but sometimes gaps can contribute to tail risk even with a modest correlation to other holdings. Liquidity conditions and market microstructure can create nonlinear responses that change the correlation landscape temporarily.

Putting the Concept to Work Without Forecasting

Correlation awareness helps align risk with capital preservation goals without making directional predictions. The focus is squarely on structure. Portfolios that acknowledge cross-asset linkage are less likely to rely on a single assumption about diversification. They are also less vulnerable to the surprise that several seemingly distinct positions were, in effect, the same bet.

Key Takeaways

- Correlation across asset classes reveals shared drivers that can cause losses to cluster, which is central to controlling drawdowns and protecting capital.

- Correlations are regime dependent and horizon specific, so rolling and conditional analyses are more informative than static long-term averages.

- Exposure measurement should be in risk terms, using volatility and sensitivity metrics, rather than notional amounts or labels alone.

- Diversification by label can be misleading. Factor mapping and stress testing help identify hidden concentration and tail co-movement.

- Correlation is a descriptive tool, not a forecast or a hedge by itself. It complements volatility analysis and scenario design to support long-term survivability.