Diversification is a foundational principle of portfolio construction. It reflects a simple idea with powerful implications: combine assets that do not move in lockstep so that the overall portfolio experiences smaller swings than its individual parts. The purpose is not to eliminate risk, which is impossible, but to structure risk so that no single event or driver dominates outcomes.

What Diversification Means and Why It Reduces Risk

Diversification reduces risk because different assets, sectors, regions, and risk factors respond differently to economic and market forces. When the price of one holding falls, another may fall less, hold steady, or rise. The combined result is a smoother return path than any concentrated position could provide.

In probabilistic terms, diversification works when returns are imperfectly correlated. If two assets do not move together one for one, their combined variability is less than the simple average of their individual variabilities. The reduction is strongest when correlations are low or negative, and weakest when correlations are near one.

The Mechanics: Variance, Covariance, and Correlation

Portfolio risk is commonly measured by variance or its square root, volatility. The variance of a two-asset portfolio depends on three elements: the variance of each asset and the covariance between them. Written plainly, portfolio variance equals the weighted sum of individual variances plus twice the product of the weights times the covariance.

Covariance can be decomposed into the correlation between the assets times the product of their volatilities. This decomposition is the key insight. When correlation is below one, the covariance term is smaller than it would be if assets moved perfectly together. That reduction pulls down overall portfolio variance.

Consider a simple numerical illustration. Suppose Asset A has volatility of 20 percent, Asset B has volatility of 10 percent, and you hold a 50 percent weight in each. If the correlation is 1.0, the portfolio volatility would be 15 percent, a straightforward average adjusted for weights. If the correlation is 0.4, the portfolio volatility falls to about 12.9 percent. If the correlation is 0.0, it falls further to about 11.2 percent. The less tightly the assets move together, the greater the risk reduction.

This logic scales beyond two assets. With many holdings, portfolio variance aggregates all individual variances and all pairwise covariances. The more low or moderately correlated exposures you include, the more the idiosyncratic noise of any single holding gets diluted by the others.

Idiosyncratic Risk and Systematic Risk

It is useful to distinguish between two broad sources of risk:

- Idiosyncratic risk is specific to a company, sector, or instrument. A product recall, a management change, or a local regulatory event are examples.

- Systematic risk is driven by market-wide forces such as business cycles, interest rate shifts, or inflation surprises.

Diversification can substantially reduce idiosyncratic risk. As the number of independent positions grows, the portfolio becomes less sensitive to any single idiosyncratic shock. Systematic risk is harder to diversify away because it affects many assets at once. The objective is to organize systematic exposures so they do not all point in the same direction under the same conditions.

Diversification at the Portfolio Level

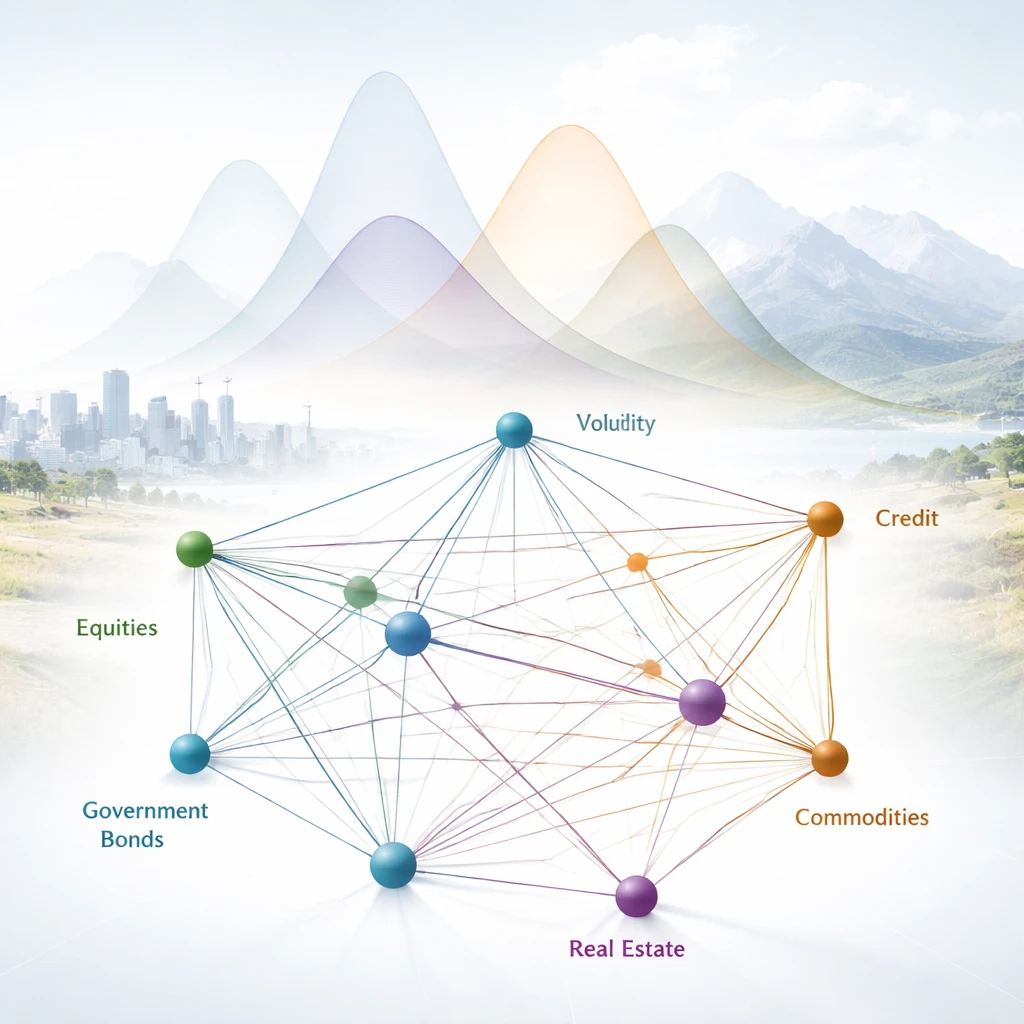

True diversification occurs at the portfolio level, not simply within a single asset class. Holding many individual stocks within one industry can reduce company-specific risk but leaves the portfolio exposed to sector-level and market-level cycles. A more diversified structure considers multiple dimensions of risk:

- Asset class: equities, government bonds, credit, real assets, commodities, and cash-like instruments exhibit different sensitivities to growth, inflation, and policy conditions.

- Geography: companies and sovereign issuers respond to regional growth dynamics, fiscal regimes, and currency movements.

- Sector and industry: technology, healthcare, energy, and consumer goods carry distinct demand drivers and regulatory frameworks.

- Factor exposures: risk characteristics such as value, quality, size, momentum, and duration can cut across asset classes.

- Currency: unhedged foreign investments add exchange rate risk that can either dampen or amplify local asset moves.

A portfolio-level view integrates these dimensions into a coherent whole. The aim is to combine return sources that are sufficiently different so that adverse outcomes in one area are moderated by others, without inadvertently layering the same risk under different labels.

How Many Holdings Are Enough

There is no universal number, but the benefits of simply adding more names diminish. Adding a stock that closely mirrors the existing portfolio does little. The incremental benefit is greatest when a new holding has a low correlation with current holdings and contributes a distinct source of risk and return.

Practical studies often show that moving from one stock to a few dozen materially reduces idiosyncratic risk in a single-country equity portfolio. Beyond that, further reduction mainly comes from diversification across sectors, geographies, asset classes, and factors, not from adding similar securities of the same type.

Beyond Stocks: Asset Class and Factor Diversification

Different asset classes respond to different macroeconomic shocks. Equities tend to be sensitive to corporate earnings growth. High-quality sovereign bonds often respond to central bank policy and flight-to-safety flows. Credit reflects both growth and default risk. Real assets, such as real estate or certain commodities, can be influenced by inflation trends and supply constraints.

These relationships are not fixed, but they provide a framework. For example, when economic growth slows unexpectedly, equities may struggle. In such periods, government bonds have historically sometimes rallied as yields fell, offsetting part of the equity losses. When inflation accelerates unexpectedly, nominal bonds may struggle, while inflation-linked bonds or certain commodities may be more resilient. The point is not to predict regimes with precision, but to ensure that the portfolio does not depend on a single regime for acceptable outcomes.

Factor diversification adds another layer. Investors often hold concentrated exposures to a single style, such as growth or value, without realizing it. Incorporating multiple complementary styles can reduce the volatility of active performance relative to a broad benchmark, even when the overall equity weight is unchanged. Across bonds, duration exposure is a dominant factor. Diversification here can involve balancing interest rate sensitivity with credit spread exposure, recognizing that these two risks are not perfectly correlated.

Diversification Across Time and the Role of Rebalancing

Diversification is not static. Correlations, volatilities, and expected return distributions evolve. A portfolio that began well balanced can drift as winners grow in weight and losers shrink. Periodic rebalancing restores intended risk allocations. It can also moderate volatility by trimming positions that have become large and adding to those that have become small, subject to costs, liquidity, and tax considerations.

Time diversification refers to the idea that taking risk across multiple periods can reduce the chance of extremely adverse long-horizon outcomes when position sizes are managed prudently. The mechanism is not a guarantee of safety. Rather, it acknowledges that shocks arrive at unpredictable times, and spreading exposure across time can reduce the impact of any single episode on long-run results.

Why Diversification Matters for Long-Horizon Compounding

Long-term capital planning is about compounding. Volatility affects compounding because geometric returns are lower than arithmetic averages when variability is present. Large drawdowns can take years to recover, and the order in which returns arrive matters for investors who add or withdraw capital over time.

By reducing the amplitude of losses, diversification can mitigate the erosion of geometric returns that comes from volatility. Smoother return paths can also lessen sequence risk, which is the sensitivity of outcomes to the timing of gains and losses relative to contributions or withdrawals. In multi-decade planning, this risk management function is central. The goal is not to chase the highest possible return in a favorable year, but to avoid instability that can derail plans when conditions change.

Moreover, diversification provides flexibility. When a portfolio is not dominated by a single risk, it can be adjusted more thoughtfully in response to new information or changing constraints because short-term stress in one area does not force disruptive changes elsewhere.

A Simple Portfolio Illustration

Consider two stylized portfolios, both targeting the same long-run return. Portfolio X concentrates in a single sector of equities. Portfolio Y spreads its equity exposure across sectors and geographies and adds a sleeve of high-quality bonds plus a modest allocation to inflation-sensitive assets. Over a decade, both might achieve similar average returns. The paths, however, can be different. Portfolio X may experience deep drawdowns when its sector falls out of favor and rapid rebounds when it returns to favor. Portfolio Y, with partial offsets from bonds and inflation-sensitive holdings at different times, may experience shallower drawdowns and fewer extreme spikes.

The diversified portfolio does not eliminate loss episodes. Instead, it reallocates risk across drivers that are less likely to all underperform simultaneously. When combined with disciplined rebalancing, the diversified structure can maintain its intended risk profile through time, which supports long-horizon planning.

Hidden Concentrations and the Illusion of Diversification

Counting line items is not enough. Portfolios can hide concentrations that only appear when viewed through a risk lens:

- Common factor exposures: different funds may all lean toward the same style, such as growth, creating an aggregate tilt that dominates results.

- Sector overlap: multiple holdings can own the same underlying companies, especially in index-tracking vehicles.

- Geographic and currency concentration: multinational companies may derive most revenues from the same region, and unhedged foreign exposure can cluster currency risk.

- Term and credit concentration: fixed income holdings may share similar duration or credit risk even if they carry different labels.

- Liquidity concentration: instruments that trade infrequently can become difficult to adjust under stress, amplifying drawdowns.

Exposing these concentrations typically requires looking beyond names to the underlying economic exposures: what conditions help or hurt each position, and how many positions are tied to the same conditions.

Correlation Is Not Static

Correlations change. In calm periods, correlations can be low, making diversification appear powerful. During market stress, many correlations rise as investors de-risk simultaneously. This phenomenon can reduce the benefit of diversification precisely when it is most needed.

This reality does not negate the value of diversification. It clarifies that diversification is about improving average outcomes and protecting against moderate shocks, not immunizing a portfolio against global panics. Some pairings, such as high-quality sovereign bonds with equities in certain economies, have historically maintained lower or negative correlations in many downturns, but the strength of that relationship varies over time and across regimes.

Costs, Constraints, and Implementation Details

The practical implementation of diversification involves trade-offs. Transaction costs, management fees, taxes, and operational complexity all matter. A highly diversified structure that is expensive to maintain can undercut the intended benefit. Liquidity considerations also influence construction. Diversification that depends on illiquid positions may be hard to maintain or rebalance when markets are stressed.

Constraints can include regulatory limits, investment policy statements, or mandate-specific objectives. Within those boundaries, the central idea remains to balance risk across distinct drivers rather than allow any single driver to dominate.

Human Capital and Total Wealth Perspective

For many individuals, the present value of future labor income, sometimes called human capital, is a large part of total wealth. If that income is highly sensitive to a particular sector or business cycle, the financial portfolio that sits alongside it may need to acknowledge that embedded exposure. While this is not an actionable prescription, the concept underscores that true diversification considers total economic risk, not just the list of financial holdings.

Measuring and Monitoring Diversification

Because diversification is fundamentally about relationships among assets, measurement focuses on how positions co-move and how they contribute to total risk. Several tools are commonly used:

- Correlation and covariance matrices: show how assets have moved relative to each other over a chosen window.

- Volatility and drawdown analysis: highlight the magnitude of typical and extreme moves, alone and in combination.

- Risk decomposition: attributes total portfolio variance to each position or factor, revealing hidden concentrations.

- Scenario and stress testing: examines how the portfolio might behave under historically observed shocks or hypothetical macro conditions.

- Liquidity and turnover diagnostics: evaluate whether the portfolio can be rebalanced under plausible trading conditions.

Monitoring over time recognizes that relationships drift. Periodic review helps keep the portfolio aligned with its intended risk structure.

Real-World Context Across Market Regimes

Historical periods illustrate how diversification can function, without implying prediction. In equity bull markets supported by strong growth and stable inflation, diversified portfolios that include fixed income and real assets may lag the highest-flying equity segments yet exhibit lower volatility. In stagflationary episodes, nominal bonds can struggle alongside equities, making inflation-sensitive assets more useful offsets. During disinflationary recessions, high-quality sovereign bonds have often helped cushion equity declines.

Global diversification can also matter. Regional recessions, currency devaluations, and policy shifts are not perfectly synchronized across countries. Exposure to different economic blocs can reduce the impact of localized stress. At the same time, truly global crises can raise correlations broadly, demonstrating that diversification mitigates but does not remove the potential for large drawdowns.

Diversification and the Shape of the Opportunity Set

Markowitz portfolio theory, often visualized through an efficient frontier, formalizes the idea that for a given level of risk there exists a combination of assets with the highest expected return, and for a given expected return there is a combination with the lowest risk. Diversification moves a portfolio toward that frontier by exploiting imperfect correlations. Even if expected returns are uncertain, the reduction in variance from sensible combinations is a concrete and measurable effect.

Importantly, diversification does not rely on forecasting short-term price moves. It relies on structural differences in how assets react to economic forces. That property makes it a robust component of long-horizon design.

Common Misconceptions

Several misunderstandings often arise:

- Diversification guarantees higher returns: it does not. The benefit is primarily risk reduction and a smoother path, which can improve the reliability of compounding but does not assure superior returns in any specific period.

- More positions always means more diversification: only if those positions bring different risks. Many similar positions can behave like a single bet.

- Diversification failed if everything fell: in broad selloffs, many assets decline together. The relevant comparison is how a diversified portfolio performed relative to a concentrated one of similar expected return and whether drawdowns were moderated.

- Diversification is set-and-forget: relationships shift and positions drift. Periodic assessment is part of maintaining diversification.

Putting the Pieces Together

To understand why diversification reduces risk, return to the mechanics. Portfolio variance is the sum of weighted variances and covariances. Covariance is shaped by correlation. If correlations are below one, the covariance terms do not add full weight to variance, and the total risk falls. At the same time, diversification aligns with long-run objectives by smoothing the sequence of returns and reducing the impact of idiosyncratic shocks. These are quantifiable effects that improve the reliability of long-term capital plans without requiring forecasts of short-term market direction.

As the portfolio expands beyond a single source of risk into multiple asset classes, geographies, sectors, and factors, idiosyncratic risk becomes small relative to systematic risk. The art of diversification is then to balance systematic exposures so that the portfolio is not overly dependent on one macro outcome, such as persistent disinflation or persistent high growth. This balance does not eliminate risk. It shapes it in a way that has historically supported more stable compounding.

Key Takeaways

- Diversification reduces risk by combining imperfectly correlated assets so that total variance is lower than the sum of parts.

- It primarily removes idiosyncratic risk and organizes systematic risk so no single driver dominates portfolio outcomes.

- The benefits depend on true differences in exposure across asset classes, sectors, geographies, factors, and currencies, not on the number of line items.

- Correlations and volatilities change over time, so diversification requires monitoring and periodic rebalancing within practical costs and constraints.

- Smoother return paths support long-horizon capital planning by mitigating large drawdowns and sequence risk, improving the reliability of compounding.