Diversification is a foundational concept in portfolio construction. It links asset selection to the basic objective of managing uncertainty while pursuing long-term growth. The term “diworsification,” popularized in practitioner circles, describes the opposite outcome: adding holdings that only make a portfolio look diverse while weakening its economic logic. This article clarifies the difference, shows how the idea operates at the portfolio level, and explains why the distinction matters for long-term capital planning.

What Diversification Really Means

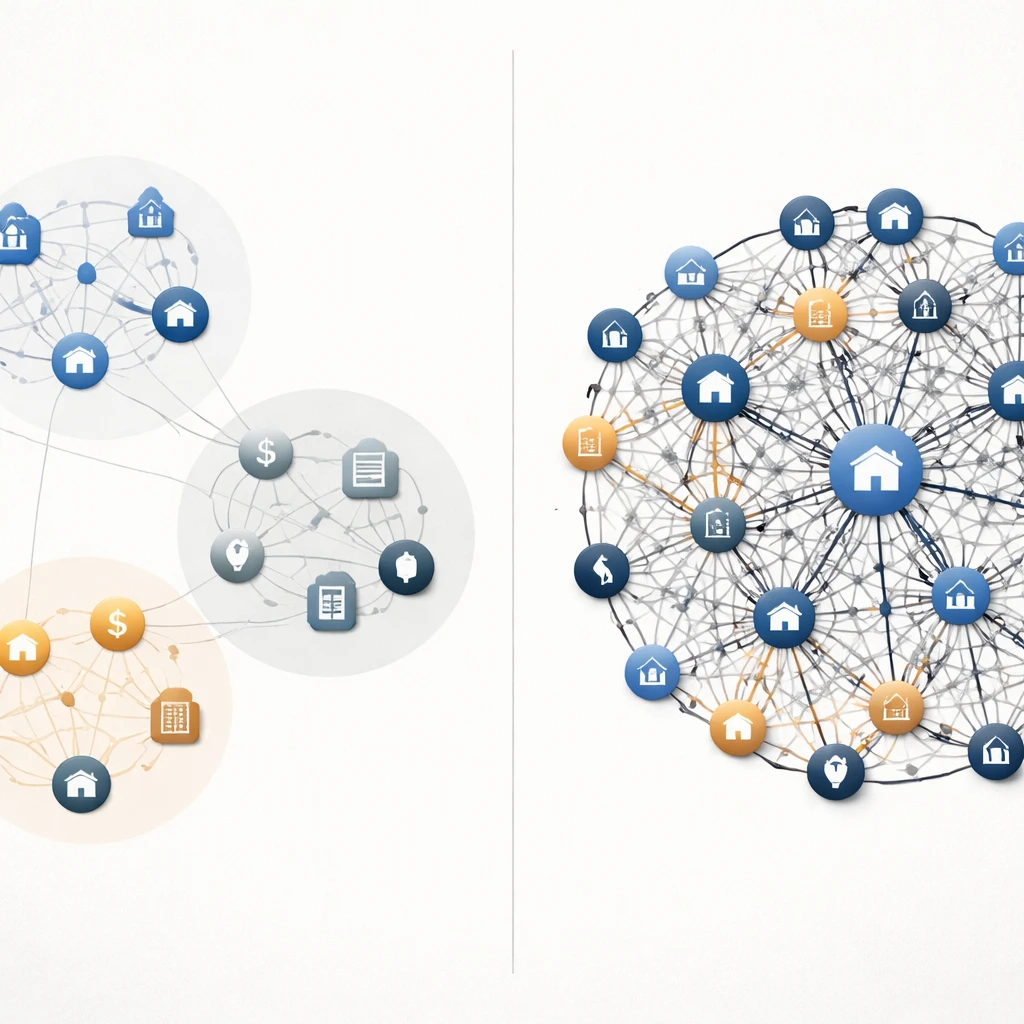

Diversification is not about owning many lines on a statement. It is about combining exposures whose returns are driven by different underlying risks so that the portfolio’s total variability and vulnerability to specific shocks are reduced. In practical terms, the usefulness of a new holding depends on three elements measured in combination:

- Its standalone risk and expected return after fees and frictions.

- Its correlation with what is already held, especially in stressed markets.

- Its effect on the concentration of the portfolio’s economic drivers, not just its number of positions.

When these elements are favorable, the portfolio’s path becomes smoother relative to the same expected return, or the expected return is improved for a similar level of risk. Importantly, correlations are not fixed. Assets that appear unrelated in quiet markets often move together during shocks. A diversified portfolio accounts for that regime dependence.

Defining Diworsification

Diworsification occurs when additions increase complexity, cost, or fragility without delivering a robust reduction in combined risk. Typical pathways include:

- Overlapping exposures that share the same dominant risk factor, which delivers little risk reduction despite more line items.

- Assets that diversify in mild conditions but correlate in crises, causing protection to disappear when needed most.

- Low-return or high-fee exposures that dilute expected compound growth without a commensurate improvement in portfolio resilience.

- Illiquid or opaque holdings that complicate rebalancing and risk measurement, raising implementation risk.

In short, diworsification is the gap between surface variety and genuine diversification. The consequence is a portfolio that is harder to manage and no more resilient to the risks that matter.

How the Concept Operates at the Portfolio Level

Portfolio construction aggregates exposures into a single risk engine. The portfolio’s variance depends on the variances of its holdings and the covariances between them. Even small allocations can materially alter total risk if they introduce a highly correlated exposure, or conversely, if they meaningfully offset a core risk. The relevant question is always marginal: does a candidate asset improve the portfolio’s balance of drivers relative to what is already present?

Consider three simple illustrations:

- Two global equity funds with similar country and sector weights will likely have a high correlation. Adding the second fund mostly replicates the first, altering the appearance of diversification but not its substance.

- An intermediate-term government bond fund exhibits lower correlation to equities in many conditions. Blending the two can lower the combined volatility and reduce deep drawdowns, although the benefit varies with interest rate regimes and macro shocks.

- A high yield bond fund often correlates positively with equities during stress because credit spreads widen when growth weakens. If a portfolio already holds substantial equity risk, adding high yield may raise exposure to the same underlying growth factor.

These examples highlight the need to map exposures to economic drivers such as growth, inflation, real rates, credit conditions, and liquidity. True diversification balances these drivers rather than accumulating many vehicles tied to the same one.

Why the Distinction Matters for Long-Term Capital Planning

Long horizons magnify the impact of compounding and drawdowns. Deep drawdowns require large subsequent gains to recover, which can be time consuming. Diversification that endures across regimes can moderate the depth and frequency of large losses and can make rebalancing more reliable. Diworsification increases the risk that a portfolio will behave like a single bet wearing different labels, leaving spending plans or funding goals vulnerable to concentrated shocks.

Long-term planning also depends on liquidity. Capital needs, such as periodic withdrawals or liability matching, call for assets that can be rebalanced or liquidated without undue cost. Opaque or illiquid holdings may promise diversification on paper but can become unavailable precisely when capital is needed. The implementation details matter as much as the statistical properties of returns.

Measuring Diversification Beyond Counting Positions

Several practical diagnostics help distinguish genuine diversification from diworsification. None is perfect in isolation, and each benefits from stress testing across regimes.

- Correlation and covariance analysis. Compute correlations not only in full-sample data but also in subsets that resemble stress periods, such as recessions or market panics. Correlations that rise toward one under stress reduce the diversification value of the pair.

- Marginal contribution to risk. Evaluate how the portfolio’s total volatility and drawdown profile change with a small increase in the weight of the candidate asset. A helpful addition lowers total risk more than its own weight would suggest or improves expected risk-adjusted characteristics after costs.

- Concentration metrics. The effective number of positions can be approximated by taking the inverse of the sum of squared weights. This reveals whether weight is spread across holdings or concentrated in a few. A separate analysis of the underlying holdings of funds can reveal overlap that reduces effective breadth.

- Diversification ratio. The ratio of the weighted average of individual volatilities to the total portfolio volatility summarizes how much risk is diversified away. A higher value suggests more independent sources of return, all else equal.

- Factor decomposition. Map each holding to common risk factors, for example market beta, size, value, quality, duration, credit, inflation sensitivity, and real rate exposure. If multiple holdings load on the same factor, the portfolio may be less diverse than it appears.

Complement these tools with scenario analysis. Shock the portfolio with moves in growth, inflation, interest rates, and credit spreads to see whether offsets appear when needed or whether losses stack up simultaneously.

Common Sources of Diworsification

Several recurring patterns produce diworsification at scale:

- Closet duplication. Owning multiple broad equity funds that track similar indexes. The aggregate exposure barely changes while fees, tracking differences, and administrative complexity increase.

- Overlapping factor tilts. Combining separate funds that each target value, quality, or momentum without recognizing that holdings overlap widely. The intended complementarity collapses into indirect concentration.

- Yield chasing in fixed income. Replacing high-quality bonds with lower-grade credit to boost yield. The portfolio’s ballast against equity drawdowns is reduced because credit risk tends to move with equity risk during stress.

- Illiquidity crowding. Adding multiple illiquid vehicles whose valuations appear smooth. Correlations measured from reported returns may be artificially low due to appraisal smoothing, masking true co-movement in adverse conditions.

- Regional home bias. Accumulating domestic-sector funds that track similar drivers, mistaking familiarity for diversification. The result is concentrated exposure to the same macro risks.

Real-World Portfolio Contexts

1. A Multi-Asset Core with Real Asset Satellites

Consider a portfolio anchored by a diversified global equity allocation and high-quality intermediate bonds. A small satellite in real assets such as listed commodities producers or an inflation-sensitive index can diversify inflation shocks that harm bonds while also providing a different earnings driver than core equities. The benefits rely on the satellite’s behavior during inflation surprises, not on its label. Adding several narrow commodity industry funds with overlapping constituents could negate the intent and increase idiosyncratic risk without increasing inflation protection.

2. Equity-Only Breadth vs Effective Breadth

An investor might hold eight equity funds spanning large cap, mid cap, small cap, and international developed markets. If the underlying holdings are dominated by a common set of mega-cap companies and sector weights are similar, the effective number of distinct bets is much lower than eight. A simple diagnostic is to look through to the top holdings and compute overlap. If two funds share most of their top positions, their correlation and factor loadings will be similar. Adding another fund from the same style box may change nothing essential. A different approach is to identify whether the overall equity sleeve captures diverse sector, region, and factor exposures without redundancy, limiting diworsification.

3. Fixed Income as Diversifier or Equity Proxy

In bond allocations, high-quality government securities typically offset equity drawdowns when growth falters, although this relationship can vary with inflation regimes. High yield bonds and bank loans, by contrast, tie more closely to corporate earnings and default risk. If a portfolio intends to hold bonds as a volatility dampener, replacing a significant fraction with credit-sensitive instruments can convert the bond sleeve into an equity proxy. The line between diversification and diworsification in fixed income is determined by how the bond sleeve behaves when equities decline sharply and when inflation surprises to the upside.

4. International Diversification and Currency

International equities add breadth in sectors, demographics, and policy regimes. However, correlations across major equity markets tend to rise in global recessions and crises. Currency exposure also affects outcomes. If domestic consumption liabilities are in a single currency, unhedged foreign currency risk may or may not help during global stress. Hedging decisions alter the diversification profile. A portfolio that indiscriminately adds regional funds without considering currency and sector overlap may find that its supposed global diversification behaves like a single global equity bet in difficult periods.

5. Alternatives, Fees, and Transparency

Private equity, real estate, and hedge fund strategies often promise low correlations to public markets. The realized benefit depends on fees, transparency, valuation methodology, and exit mechanics. Appraisal-based return series can understate volatility and correlation, creating an illusion of diversification that evaporates when liquidity is needed. Even when exposures are genuinely distinct, high costs can erode the expected contribution to long-term compound growth. Diworsification arises when attractive narratives overshadow careful assessment of drivers, correlations in stress, and implementation details.

Risk Drivers and Regime Dependence

Thinking in terms of risk drivers clarifies what it means to diversify. Equity returns often depend on earnings growth and risk appetite. High-quality bonds respond primarily to changes in real rates and inflation expectations. Real assets such as commodities and certain infrastructure assets are sensitive to inflation surprises and supply shocks. Credit instruments reflect both interest rate and growth risk through default and recovery dynamics. Cash and short-duration instruments carry minimal price risk but substantial reinvestment risk over long horizons.

Regimes matter. In environments dominated by disinflationary slowdowns, equities and long-duration bonds can move in opposite directions, offering strong diversification. In inflationary shocks, both may decline simultaneously as discount rates rise and earnings margins compress. Portfolios constructed with awareness of these regime shifts are less dependent on a single relationship that may not hold across time. Diworsification often appears when portfolios rely on correlations measured in one regime and extrapolate them to all others.

Costs, Frictions, and the Complexity Trap

Even when an asset provides statistical diversification, costs can undermine its value. Trading spreads, management fees, taxes, and financing costs reduce net returns. A small reduction in expected return compounds into a large difference over long horizons. Complexity also carries opportunity cost. Monitoring many small positions takes time and may cause delays in rebalancing. Complexity can also obscure whether the portfolio still matches the investment policy or liability profile. Diworsification frequently sneaks in through incremental additions that each appear harmless but collectively create a portfolio too complex to manage effectively.

Rebalancing and the Mechanics of Staying Diversified

Diversification is a dynamic property. Asset weights drift as markets move, sometimes changing the portfolio’s risk balance more than its market value suggests. A portfolio that starts with balanced risk can evolve into a concentrated bet if winners grow unchecked. Rebalancing disciplines the weights back toward a target structure, helping maintain the intended diversification across risk drivers. However, rebalancing into assets that only seem diverse can inadvertently add to diworsification. Monitoring correlations, factor exposures, and liquidity helps ensure that rebalancing restores balance rather than amplifies hidden concentrations.

Diagnostics to Separate Diversification from Diworsification

Several practical checks support a disciplined process. These are analytical tools rather than prescriptions.

- Correlation heatmaps across regimes. Build correlation matrices for normal periods and for stress windows. Look for pairs that switch from low correlation to high correlation during stress, and treat their diversification value as conditional.

- Factor loadings audit. Decompose each fund or asset into common factors. Summarize the portfolio’s total exposure to market beta, duration, credit, value, quality, momentum, and inflation sensitivity. Identify redundancies and gaps.

- Overlap analysis. For funds, aggregate their top holdings. Compute the share of the portfolio accounted for by the largest overlapping positions. Identify whether multiple funds rely on the same names or sectors.

- Effective number of bets. Convert weights into an effective breadth measure using the inverse of the sum of squared weights. Use a similar approach at the level of risk contributions, not just capital allocations.

- Stress scenarios and drawdown mapping. Model historical or hypothetical shocks, such as an inflation surprise, a growth recession, a rapid rate hike, or a liquidity squeeze. Observe whether losses offset or compound.

- Implementation review. Check fees, tax implications, liquidity, and settlement. An asset that is hard to rebalance or incurs large costs may fail to deliver its theoretical benefit when it matters.

Naive Diversification and Cognitive Biases

The human tendency to equate more with better lies behind many diworsification errors. A few common biases are worth recognizing:

- Naive diversification. Spreading capital evenly across many choices without understanding their shared drivers can feel safe while concentrating risk.

- Recency bias. Adding assets that performed well recently can crowd the same winning factor, increasing exposure to a mean-reversion risk.

- Home and familiarity bias. Favoring domestic sectors or well-known brands can lead to regional and sector clustering.

- Yield illusion. Focusing on income level rather than total return and risk can drive portfolio bond sleeves toward credit risk that behaves like equity risk during downturns.

- Action bias. The urge to change holdings rapidly can increase turnover costs and degrade the compounding benefits of a sound structure.

Linking Diversification to Long-Term Objectives

Long-term capital planning often involves explicit objectives such as sustaining withdrawals, funding future liabilities, or preserving purchasing power. Diversification supports these objectives by moderating outcome variability and by increasing the reliability of rebalancing across cycles. A diversified portfolio also makes it easier to align assets with time horizons. Short-horizon needs can be funded by higher-liquidity, lower-volatility holdings, while long-horizon growth is pursued with riskier assets whose drawdowns can be tolerated when they are not linked to near-term liabilities.

Diworsification complicates this mapping. If the supposedly conservative portion of a portfolio is loaded with equity-like credit risk, liquidity needs may collide with market stress. If the growth portion is spread across many funds that all track the same factor, the expected growth path may be more fragile than it appears. A portfolio aligned with objectives relies on genuine diversification of risk, not just proliferation of vehicles.

Illustrative Portfolio Narratives

Narrative A: Concentration Hidden in Variety

An investor allocates across seven equity funds, a high yield bond fund, and a preferred stock fund. On paper, nine funds appear diverse. A factor decomposition reveals that over 85 percent of total risk comes from global equity beta and credit spread risk. During a growth shock, all sleeves lose together. The diagnosis indicates diworsification: variety without independence of drivers.

Narrative B: Balanced Drivers with Simple Implementation

Another portfolio uses broad global equity, high-quality bonds, and a measured allocation to inflation-sensitive assets. The number of vehicles is limited. Overlap analysis shows distinct holdings. Stress tests indicate that growth shocks and inflation shocks do not produce identical losses across sleeves. The portfolio is not immune to loss, but its drivers are balanced. Complexity is kept in check, which makes monitoring and rebalancing feasible.

Practical Considerations Without Prescriptions

There is no universally optimal mix. The role of diversification is to connect portfolio structure to identifiable risk drivers, costs, and implementation realities. A disciplined process typically documents intended factor exposures, sets tolerance ranges for concentration, and outlines how to respond when correlations or market regimes shift. The process recognizes that estimation error is unavoidable. Relying on multiple diagnostics rather than a single statistic tends to improve robustness.

Ultimately, diversification versus diworsification is a question of economic substance. Does the portfolio combine exposures that behave differently for reasons grounded in how cash flows and discount rates respond to the world, or does it assemble numerous instruments that trace back to the same source of risk? Keeping the answer visible in both normal times and stress is the core of resilient portfolio construction.

Key Takeaways

- Diversification reduces portfolio vulnerability by combining exposures tied to different economic drivers, not by simply increasing the number of holdings.

- Diworsification arises when additions add complexity, cost, or correlated risk, creating surface variety without improving resilience.

- Portfolio-level evaluation focuses on correlations across regimes, marginal contribution to total risk, factor exposures, and implementation frictions.

- Real-world pitfalls include overlapping funds, credit-heavy bond sleeves that mimic equity risk, and illiquid assets that appear diversifying due to smoothed returns.

- For long-term capital planning, genuine diversification supports steadier compounding and more reliable rebalancing, while diworsification makes outcomes more fragile.