Concentration risk is the vulnerability that arises when a significant portion of a portfolio’s value or risk is tied to a limited set of positions or exposures. It is a structural feature of portfolio construction and an essential consideration for building resilient allocations. While concentration can reflect deliberate conviction or constraints, it also increases the range of possible outcomes and can amplify drawdowns precisely when stability is most valuable. Understanding where concentration lives, how to measure it, and why it matters over long horizons is central to prudent diversification.

Defining Concentration Risk

Concentration risk occurs when portfolio performance depends heavily on a small number of drivers. These drivers can be individual securities, sectors or industries, geographic regions, currencies, factors such as value or momentum, credit quality buckets, duration bands, or even a handful of fund vehicles that hold similar underlying assets. The concept is broader than simply owning a few names. A portfolio with many holdings can still be concentrated if those holdings move together or share the same economic sensitivities.

At its core, concentration risk is about dependency. When a single dependency dominates, the portfolio becomes more fragile to surprises that affect that dependency. Diversification, by contrast, spreads dependency across multiple sources of return that are not perfectly correlated. The goal in portfolio construction is not to eliminate concentration entirely, which is neither feasible nor necessarily desirable, but to understand it and align it with the investor’s objectives and constraints.

Where Concentration Appears in Portfolios

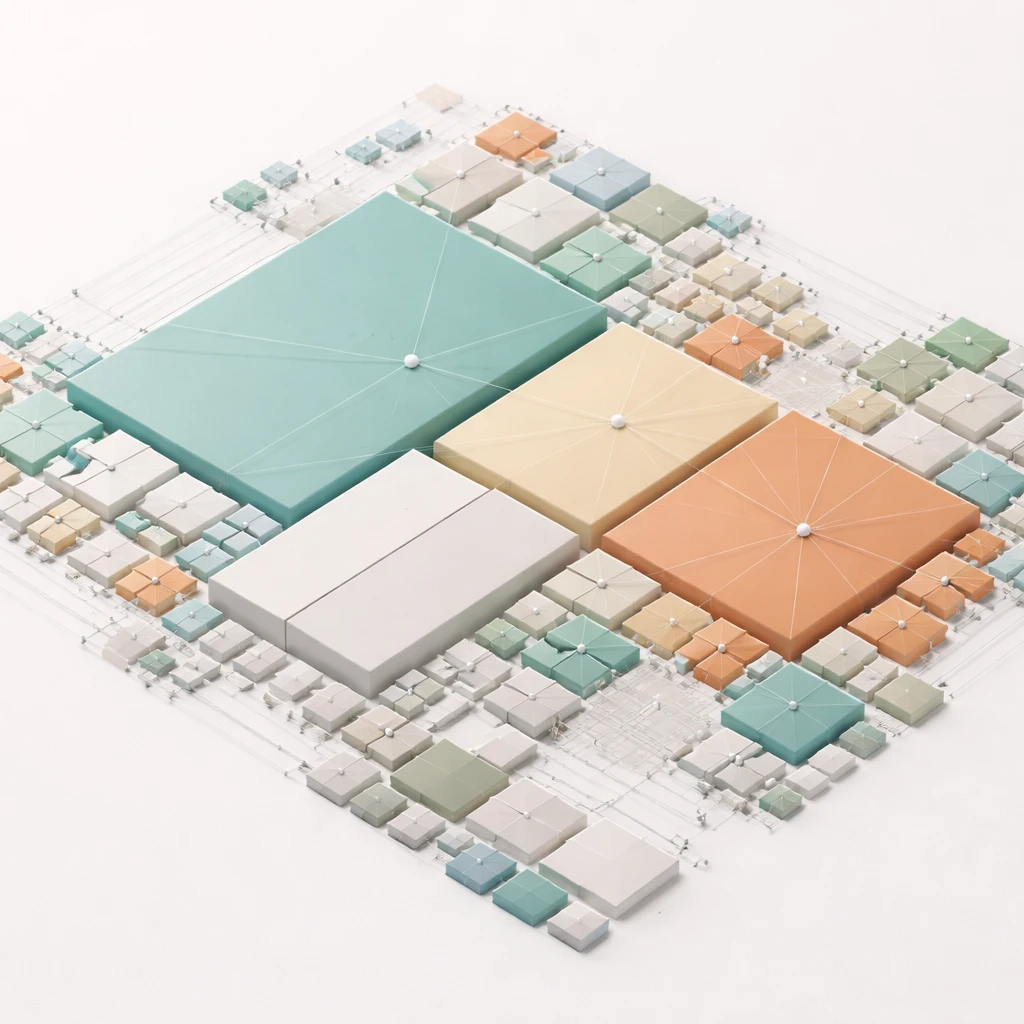

Concentration can manifest along several dimensions. The most visible is position size. A few large weights in individual securities or funds can drive most of the variance in returns. Less visible forms include overlapping exposures across funds, correlated sector bets that move together, or unrecognized factor tilts that dominate risk without being obvious from holdings counts.

Position-Level Concentration

Classic concentration arises when a small number of line items carry a large fraction of portfolio weight. Analysts often examine the weight of the top 5 or top 10 holdings, the largest single position, and the distribution of weights across the full set of positions. A commonly used summary measure is the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, defined as the sum of squared portfolio weights. The effective number of holdings equals one divided by that sum. If a portfolio has an effective number of 7, its weight distribution behaves as if it held seven equal-weight positions, even if the actual number of holdings is far larger.

Sector, Industry, and Theme Concentration

Exposure to a single sector or theme can dominate outcomes during regime shifts. Technology, energy, financials, or health care may exhibit long periods of outperformance followed by abrupt reversals. Concentration at the sector level can emerge indirectly, for example when several funds each emphasize the same industry. Analysts therefore aggregate holdings by classification system and evaluate the share of the portfolio in each category, then examine how these categories co-move.

Geographic and Currency Concentration

Portfolios may cluster in one region or currency. An investor whose liabilities are in a home currency is exposed to currency concentration if a large share of assets is denominated elsewhere without offsets. Geographic concentration also introduces policy, legal, and macroeconomic risks tied to that region’s conditions. These exposures can be hidden when multi-asset funds report aggregate returns but not currency or region breakdowns.

Factor Concentration

Even with many line items, portfolios can be concentrated in a small set of systematic factors. For equities, these often include market beta, size, value, quality, momentum, and low volatility. Credit portfolios carry factors such as credit spread beta, duration, and liquidity. Real assets are sensitive to inflation and real rates. If factor loadings cluster heavily in a single direction, a portfolio will rise and fall with that factor. For example, an allocation dominated by quality-growth equities, long duration bonds, and venture capital may be more sensitive to real interest rates than it appears from holdings alone.

Issuer and Counterparty Concentration

Fixed income portfolios can be dominated by a handful of issuers, guarantors, or counterparties. Concentration here raises exposure to downgrade or default events, and to legal terms that can transmit losses across multiple bonds from the same issuer. In derivatives, counterparty concentration matters through collateral terms and netting sets. These exposures become particularly important when liquidity is scarce.

Liquidity and Implementation Concentration

Liquidity can be concentrated in a few assets or channels. Portfolios that rely on one market maker, one lending facility, or a small set of exit routes face implementation risk if those routes close temporarily. Concentration in illiquid assets can also interact with spending needs, creating forced sales at unfavorable times.

Why Concentration Risk Matters for Long-Term Capital Planning

Long horizons often amplify the impact of concentration, rather than dampen it. The path of returns matters for compounding and for meeting cash flow needs. Several mechanisms underline the importance of concentration in long-term planning.

Drawdowns and Recovery Math

A concentrated portfolio is more likely to experience large drawdowns when its dominant exposures underperform. Recovery from deep losses requires disproportionate gains. A 50 percent drawdown needs a 100 percent subsequent increase to return to the starting level. The time required to regain losses increases nonlinearly with drawdown depth. Portfolios that must fund ongoing spending or liabilities can face difficult trade-offs during recovery periods if losses are concentrated in the assets earmarked for those obligations.

Compounding and Volatility Drag

Geometric returns fall as volatility rises, all else equal. Concentration increases the variance of outcomes and therefore can lower long-run compounded growth relative to a less concentrated mix with similar arithmetic expectations. This effect does not imply that lower concentration always produces higher long-run growth. It indicates that for a given set of expected returns, greater dispersion reduces the compound rate, which is central for funding multi-decade goals.

Estimation Error and Model Risk

Expected returns and correlations are uncertain. Concentration magnifies the consequences of estimation error because portfolio outcomes hinge on fewer assumptions. If a forecasted advantage for one sector or factor fails to materialize, a concentrated portfolio bears most of that error. Dispersed allocations distribute estimation risk across more independent bets, which reduces sensitivity to any single mistake in inputs.

Liquidity, Spending, and Governance

When a portfolio supports spending or collateral needs, concentration can create timing mismatches. If the concentrated exposure is also illiquid, the portfolio may need to sell what is liquid, possibly reinforcing concentration in what remains. Governance structures also matter. Concentration can create heightened performance dispersion relative to peers or benchmarks, which increases behavioral pressures that influence decision-making.

Regulatory and Fiduciary Contexts

Many institutions operate within guidelines that set limits on single positions, sectors, or issuers. These frameworks reflect the understanding that concentrated exposures raise the probability of large adverse outcomes. Even when not mandated, similar principles are used as internal risk controls to align portfolios with stated risk tolerances and objectives.

Measuring Concentration at the Portfolio Level

Diagnosis begins with clarity on what is being concentrated. Each dimension calls for its own metric. No single statistic captures the full picture, so practitioners combine several diagnostics.

Weights and Effective Number of Positions

The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index equals the sum of squared weights across positions, sectors, or any chosen category. A portfolio that holds ten equal-weight positions has an HHI of 0.10, which corresponds to an effective number of 10. If one position grows to 50 percent of the portfolio while the remaining nine share the rest equally, the HHI rises to 0.5 squared plus nine times 0.0556 squared, and the effective number falls sharply. This simple calculation helps quantify how much the weight distribution has tilted toward a few holdings.

Risk Contribution Concentration

Concentration should be evaluated in risk units, not only in weights. A security with a modest weight but very high volatility or high correlation with the rest of the portfolio can contribute disproportionately to total risk. Risk contribution frameworks compute each position’s share of portfolio variance. If a handful of positions account for most of the variance, the portfolio is risk-concentrated even if weights look balanced. The same logic applies to sectors and factors.

Factor Exposure Diagnostics

Multi-factor models estimate how much a portfolio’s return co-moves with systematic drivers. By regressing returns on factor returns or by applying holdings-based risk models, analysts obtain factor loadings and contributions to risk. If a small set of factors explains most of the portfolio’s variance, then the portfolio is factor-concentrated. This often reveals hidden concentration embedded in ostensibly diversified allocations.

Overlap and Look-Through Analysis

Holdings that appear diversified by fund label may be concentrated when viewed through to the underlying securities. Two broad equity funds can share many top positions, producing significant overlap. Overlap can be quantified by summing the minimum weight across overlapping securities or by computing a similarity index. Look-through is equally important in multi-asset funds that hold other funds, where multiple layers can obscure common exposures.

Issuer and Counterparty Limits

Fixed income concentration is often measured by the fraction of exposure to the top issuers, the share in a single credit sector, and the distribution across ratings and maturities. Counterparty exposure in derivatives can be summarized by potential future exposure, collateral terms, and concentration of netting sets. These diagnostics link concentration to credit and funding risks that behave asymmetrically during stress.

Liquidity Concentration and Capacity

Liquidity analysis considers average daily volume, bid-ask spreads, market depth, and settlement infrastructure. If a significant portion of the portfolio resides in assets that trade infrequently, or if many positions rely on the same liquidity providers, shocks can have outsize effects. Capacity assessments ask whether the portfolio’s size relative to market turnover implies that exits would be slow or price-moving during stress.

Scenario and Stress Concentration

Historical or hypothetical scenarios reveal how concentration plays out under stress. Analysts map how sectors, factors, and issuers behaved during past episodes such as inflation spikes, credit crunches, or policy shifts, then estimate portfolio performance given current exposures. Concentration is evident when a small number of shocks explain most of the simulated drawdown.

Real-World Portfolio Contexts

Context 1: Name and Sector Concentration in Equities

Consider a portfolio of 30 equities where the top 5 names comprise 55 percent of the weight, all in a single industry such as software. During a period of strong growth expectations and falling discount rates, such a portfolio may deliver outsized gains. If rates rise and the sector derates together, the combination of name and sector concentration can magnify the decline. Even if the remaining 25 names hold up, the aggregate outcome is driven by the dominant cluster.

Context 2: Hidden Overlap Across Index Funds

An investor might hold three large-cap index funds from different providers and a technology sector fund. The labels differ, but the top holdings could be largely the same. If the top 10 names represent 30 to 40 percent of each large-cap fund and overlap with the sector fund, the combined portfolio becomes more concentrated than intended. A look-through overlap metric would highlight that the same handful of companies drive a large share of total risk.

Context 3: Credit and Issuer Concentration

A corporate bond portfolio focused on investment-grade names could still be concentrated if 40 percent of its market value comes from three issuers in the same industry, each with similar covenant packages. A downgrade cycle or litigation affecting that industry may transmit across those holdings. The risk is not only default risk but also spread widening that reduces mark-to-market values precisely when liquidity is thin.

Context 4: Duration and Real Rate Sensitivity

A multi-asset mix that combines long-duration government bonds, growth equities, and certain real estate vehicles may concentrate sensitivity to real interest rate shocks. Even if the portfolio includes many securities, the common macro driver can dominate. A parallel rise in real yields can produce simultaneous pressure on bond valuations and on equity segments that discount long-duration cash flows, yielding a larger combined drawdown than holdings counts would suggest.

Context 5: Currency and Liability Alignment

Suppose a saver plans future expenses in a home currency but holds a significant share of assets in a foreign currency without offsetting exposures. If the home currency appreciates for macroeconomic reasons unrelated to the foreign assets’ fundamentals, the portfolio’s purchasing power declines. The risk arises from currency concentration relative to spending obligations, not necessarily from the performance of the underlying securities in local terms.

Conceptual Approaches Used to Manage Concentration

Practitioners use several conceptual tools to observe and frame concentration risk. These tools are descriptive and analytical. They help clarify trade-offs without implying any specific action.

Risk Budgeting Frames

Risk budgeting allocates portions of the portfolio’s permitted volatility or drawdown tolerance to categories such as asset classes, sectors, or factors. If a single category consumes most of the budget, the portfolio is understood to be concentrated along that dimension. This frame is especially useful when return forecasts are uncertain, because it emphasizes the distribution of potential outcomes in risk units.

Position and Exposure Limits

Many institutions define maximum weights for single positions, sectors, issuers, or regions, and minimum counts for issuers in credit portfolios. These limits are structural tools to prevent inadvertent concentration. They can be absolute or relative to a benchmark. The purpose is to ensure that no single dependency dominates without clear acknowledgement.

Look-Through and Overlap Monitoring

Systematic look-through aggregates holdings across all vehicles to capture underlying exposures. Overlap monitoring quantifies common holdings across funds and calculates the share of the portfolio that depends on the same names. These diagnostics are especially relevant when using exchange-traded funds and mutual funds that may share the same top positions across different labels.

Factor and Scenario Analysis

Factor models and scenario analysis complement weights-based views. Factor diagnostics identify concentration in systematic drivers. Scenario analysis examines the portfolio under regime shifts that historically have tested specific exposures, such as inflation surprises or funding stresses. Both approaches help reveal forms of concentration that are not obvious from the holdings list.

Liquidity Bucketing and Capacity Checks

Liquidity bucketing groups assets by expected time and cost to liquidate. Capacity checks relate portfolio size to typical market depth. If a large share of value sits in buckets that require extended time to trade, the portfolio carries liquidity concentration. Observing this helps align expectations about how quickly the portfolio can adapt during stress, even without changing the allocation.

Rebalancing and Drift Awareness

Concentration often grows through performance drift. An initially diversified allocation can become concentrated as winners compound. Monitoring drift highlights when exposure has shifted away from the intended risk profile. The observation itself is informative because it indicates that recent performance has increasingly tied the portfolio to a subset of drivers.

Trade-Offs and Nuances

Concentration is not inherently negative. It can reflect a deliberate view about the efficiency of capital deployment, or the desire to align with a specific mission or constraint. Some investors accept higher concentration in exchange for the possibility of differentiated outcomes. The critical point is that concentration raises the range of potential paths and deepens sensitivity to specific risks. Diversification, for its part, can dilute exposures and introduce complexity and cost. The question is which exposures are essential and which concentrations are incidental.

Additionally, correlations change over time. During stress, correlations across assets and sectors often rise, causing diversification to provide less protection than historical averages suggest. This does not negate the value of dispersion, but it does mean that concentration should be evaluated under a range of correlation regimes. Scenario-based thinking and robust risk models help avoid overreliance on a single historical window.

Common Misconceptions

Several persistent misconceptions complicate the discussion of concentration risk:

- More holdings automatically mean better diversification. In reality, adding highly correlated positions may not reduce risk meaningfully. The shape of correlations matters more than the count.

- Broad market indexes eliminate concentration. Market-capitalization weighting can itself be concentrated in the largest companies or dominant sectors. Index exposure should be assessed for weights, factors, and overlap with other holdings.

- Diversification eliminates losses. Diversification spreads risk, but it cannot remove losses caused by market-wide shocks. It primarily mitigates exposure to idiosyncratic or narrow-factor events.

- Only single-name bets create concentration. Concentration across sectors, factors, currencies, or liquidity profiles can be equally important and sometimes more binding in stress.

- Concentration is visible without detailed data. Hidden overlap across funds and layers requires look-through to uncover shared dependencies.

A Non-Exhaustive Diagnostic Checklist

The following questions illustrate how practitioners often examine concentration without implying any action:

- What share of portfolio weight is in the top 5 and top 10 positions, and how has this changed over time due to drift?

- What is the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index by position, sector, and region, and what is the effective number derived from each?

- Which positions, sectors, or factors contribute most to total portfolio variance, and what fraction of risk do the top contributors represent?

- How much overlap exists across fund holdings, and what percentage of the portfolio depends on the top overlapping names?

- What is the distribution of exposure across issuers, ratings, and maturities in fixed income, and how large are the top counterparty exposures in derivatives?

- How concentrated is currency exposure relative to spending or liability currency, and how sensitive is purchasing power to currency moves?

- What portion of the portfolio sits in less liquid buckets, and how would typical exit timelines interact with potential cash needs?

- Under historical or hypothetical scenarios, which shocks dominate the simulated drawdown, and do these map to known concentrations?

Building Resilience Through Awareness

Resilient portfolios are explicit about the concentrations they accept and the ones they avoid. The analytical tools described above do not prescribe outcomes. They provide clarity about where risk originates and how it might behave when conditions change. In long-term capital planning, that clarity supports decisions about spending policies, liquidity reserves, and the alignment of exposures with objectives and constraints.

Effective governance emphasizes documentation of intended concentrations, ongoing monitoring of drift, and preparedness for a range of correlation and liquidity regimes. Because expected returns and volatilities evolve, periodic reassessment is part of treating concentration as a dynamic feature rather than a static attribute. With that lens, concentration risk becomes a measurable and manageable dimension of portfolio construction rather than an afterthought.

Key Takeaways

- Concentration risk is dependency on a limited set of positions or exposures, which amplifies outcome dispersion and drawdowns.

- It appears across multiple dimensions, including positions, sectors, factors, geography, currency, issuer, and liquidity channels.

- Long-term capital planning is sensitive to concentration because drawdowns, compounding, liquidity needs, and estimation error interact over time.

- Diagnosis combines weights-based metrics, risk contribution analysis, factor models, overlap look-through, issuer limits, and scenario tests.

- Resilience grows from clear identification of accepted concentrations, transparency about drift, and awareness of how correlations and liquidity change under stress.