Funding a trading account is not primarily a question of picking securities or timing the market. It is a portfolio construction decision that addresses how much capital can be placed at higher turnover and higher risk without undermining the objectives of long-term wealth accumulation. A clear framework for funding trading accounts specifies the size, source, and rules for transfers between a trading sleeve and the rest of the portfolio. Done well, this framework reduces the chance that short-term volatility disrupts long-horizon plans, while still permitting active risk taking for those who wish to practice it.

Defining Funding Trading Accounts

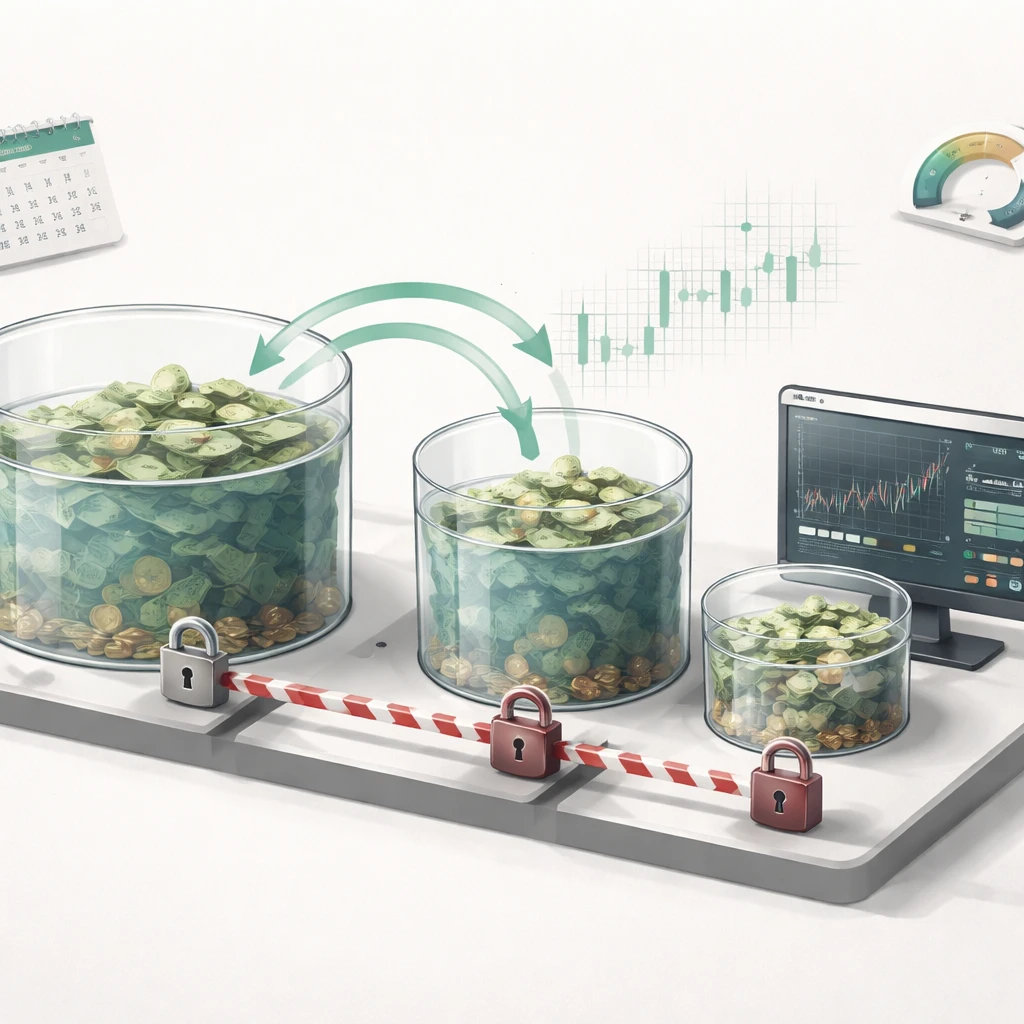

Funding Trading Accounts refers to the policies and mechanics used to allocate, maintain, and govern a dedicated trading sleeve within a broader household or institutional portfolio. The concept separates two distinct forms of capital:

- Long-term capital supports multiyear or multidecade objectives such as retirement, education, or endowment spending. It often prioritizes diversification, cost control, and tax efficiency.

- Trading capital is sized for shorter-horizon, higher-turnover activity that may carry higher volatility, idiosyncratic risk, and operational demands.

Funding policies address four questions:

- What initial amount is allocated to the trading sleeve and from which source does it come

- Under what conditions are profits transferred out of the trading sleeve to the long-term pool

- Under what conditions, if any, is additional capital transferred into the trading sleeve

- What hard limits prevent trading losses or leverage from impairing long-term assets

This is a governance problem before it is a market problem. The objective is to ring-fence risk, preserve the compounding engine of the core portfolio, and create predictable rules that reduce ad hoc decision making under stress.

Why the Separation Matters for Long-Term Planning

Long-term compounding is sensitive to large, unrecoverable losses. Trading accounts, by design, accept more path volatility. A funding policy matters because it:

- Protects core compounding. Losses in the trading sleeve are prevented from cascading into the long-term pool through predefined boundaries and zero or limited bailout rules.

- Clarifies risk budgets. The investor knows how much loss the trading sleeve can sustain without jeopardizing essential goals.

- Improves decision hygiene. When drawdowns occur, precommitted rules reduce emotional transfers, which are a common source of long-term plan failures.

- Creates liquidity discipline. Trading often requires ready collateral. Funding rules ensure liquidity is set aside without raiding emergency reserves or required distributions.

- Enables performance evaluation. Clear segmentation allows separate measurement of the trading sleeve and the core, avoiding attribution errors.

Portfolio-Level Architecture

A practical way to locate a trading sleeve within a total portfolio is through capital segmentation. The portfolio is divided by purpose, time horizon, and tolerance for variability. While each household or institution is unique, a common architecture includes three buckets.

Capital Buckets

- Liquidity reserve. Cash and near-cash that cover near-term expenses and contingencies. This bucket should not be a source of trading collateral.

- Long-term core. Diversified assets intended to compound over long horizons. Policy allocations, rebalancing bands, and cost-aware implementation typically govern this bucket.

- Trading account. A discrete account or subaccount that hosts higher turnover activity. It may be at a different custodian or broker and can use separate tools or margin agreements.

Segmentation is most effective when the boundaries are operationally real, not only conceptual. Separate accounts, distinct custodians, and independent reporting all reinforce the separation.

Flow Rules Between Buckets

Funding policies specify when capital can move and in which direction.

- Initial seed. A one-time allocation from surplus capital funds the trading sleeve. The amount should be consistent with the total risk budget and loss-absorption capacity of the household or institution.

- Profit skimming. Net profits above a preset threshold are periodically transferred from the trading sleeve to the long-term core. This locks in gains and prevents size creep that can raise risk unintentionally.

- Re-seeding constraints. Transfers into the trading sleeve after losses are either prohibited or limited by strict caps and cooling-off periods.

- No encroachment. Liquidity reserve assets are not used to fund trading. This protects near-term obligations from market variability.

These rules ensure that the trading sleeve can contribute positively while remaining contained if results are poor.

Sizing the Trading Allocation

The allocation to trading should be grounded in risk capacity, not return hopes. Several determinants matter:

- Loss-absorption capacity. The amount of capital that could be lost in the trading sleeve without forcing changes in spending, savings, or long-term allocations. This is a practical ceiling.

- Time horizon and income stability. Longer horizons and stable income may support a modest trading sleeve, while short horizons and uncertain income argue for smaller sizing.

- Strategy variability. Even without specifying strategies, some trading approaches tend to have higher volatility and fat-tail risk. The more variable the approach, the smaller the prudent allocation.

- Concentration and leverage. The use of margin, derivatives, or concentrated positions raises exposure to sharp drawdowns and liquidity calls, which should constrain allocation.

- Behavioral tolerance. Some investors can psychologically tolerate a 30 percent drawdown in a ring-fenced sleeve. Others find 10 percent stressful. Self-knowledge matters because tolerance affects rule adherence.

A simple way to scale is to set a maximum dollar loss tolerance for the trading sleeve, then work backward from plausible worst cases. For example, if the maximum tolerable loss is 40,000 on a one million total portfolio, and the trading approach can plausibly experience a 50 percent drawdown in a severe year, then the initial trading allocation might be capped near 80,000. This is not a recommendation. It shows how aligning dollar loss tolerance with plausible drawdowns yields a starting size.

Stress alignment is crucial. If the trading approach sometimes correlates with equity selloffs, then a sharp market decline could simultaneously hit the core and the trading sleeve. Sizing should reflect joint stress, not isolated averages.

Funding Mechanics and Transfer Policies

Funding policies are most effective when they specify processes in observable terms rather than intent alone.

Initial Funding and Re-seeding

- Initial seed. Transfer a defined amount from surplus capital or from a planned portion of the long-term allocation. Document the source and date.

- Cooling-off and caps. If re-seeding is allowed after a loss, use a cooling-off period and a cap. For instance, re-seeding could be limited to once per year and only up to the original seed. If a loss breaches a hard floor, re-seeding may be prohibited for a set period.

- Non-recourse rule. Prohibit transfers from long-term capital to meet margin calls in the trading sleeve. If the trading sleeve fails, it liquidates or de-risks, but it does not draw on the core.

Profit Withdrawals

- Threshold-based skimming. When the trading sleeve equity exceeds a preset threshold, transfer a portion of the excess to the core. Thresholds can be based on a percentage above the last high-water mark or on calendar intervals.

- High-water mark. Use a high-water mark to determine profits available for transfer. This prevents premature withdrawals during normal fluctuation.

- Calendar cadence. Monthly or quarterly reviews are typical. Very frequent transfers can create frictional costs, while very infrequent transfers can allow position sizes to drift.

Drawdown Controls

- Hard stop on sleeve equity. Establish a maximum drawdown for the sleeve that triggers de-risking to cash or a minimal exposure level.

- Position-level risk constraints. Limit single-position and sector exposures within the trading sleeve to avoid concentration failures spilling over into the sleeve as a whole.

- Leverage guardrails. Set maximum margin utilization and derivatives exposure. These guardrails keep trading volatility within the planned range and limit tail risk.

Liquidity, Custody, and Margin Considerations

Account selection and collateral practices can undermine or reinforce the funding policy.

- Separate custody. Hosting the trading sleeve at a different broker can reduce the chance of accidental transfers and creates operational clarity.

- Cash sweep and collateral. Understand how cash is swept and what assets can be pledged as collateral. Avoid cross-collateralization with long-term accounts if possible.

- Settlement and liquidity. Higher turnover activity requires quick access to cash and collateral. The sleeve should maintain an appropriate cash buffer to meet settlement, fees, and potential margin calls without external funding.

- Currency exposure. If the trading sleeve holds instruments in multiple currencies, consider whether unhedged currency swings could interact with the core portfolio in stressed periods.

Taxes, Frictions, and Constraints

Taxes and transaction costs affect the economics of funding and withdrawals. While jurisdiction-specific advice is outside scope, several general considerations apply:

- Turnover and short-term rates. Higher turnover often realizes short-term gains or losses that can carry different tax treatment than long-term holdings. This affects net-of-tax performance and the timing of transfers.

- Wash sale and lot management. Frequent trading can interact with loss disallowance rules and lot identification. Recordkeeping and broker features should align with the strategy’s frequency.

- Account wrappers. Retirement or tax-advantaged accounts can have restrictions on margin, derivatives, or withdrawals. Funding policies should respect these constraints to avoid penalties or liquidity issues.

- Frictional costs. Commissions, slippage, borrow fees, and financing costs scale with activity. Funding sizing should reflect realistic net returns after these costs.

Risk Measurement and Governance

Defining measurement and oversight practices turns a funding idea into a durable process.

- Policy document. Write a simple policy that states the trading sleeve’s purpose, size, allowable instruments, leverage limits, transfer rules, and drawdown procedures. Keep it concise and testable.

- Reporting cadence. Review monthly or quarterly. Track sleeve return, volatility, max drawdown, margin utilization, gross and net exposure, and contributions or withdrawals.

- Attribution. Separate alpha from beta by comparing the sleeve’s results to relevant factors or benchmarks. This helps identify whether results stem from market direction, specific exposures, or trading skill.

- Escalation triggers. Define conditions that trigger a review or suspension, such as breaches of leverage limits, abnormal slippage, or operational errors.

Illustrative Real-World Portfolio Contexts

These examples are simplified and for illustration only. They show how funding policies can be tailored to differing risk capacities and objectives.

Early-Career Professional

Consider an early-career professional with a growing salary, an emergency fund covering several months of expenses, and a diversified retirement account. The individual wishes to allocate some capital to active trading. A possible policy could look like this in structure:

- Seed and size. Allocate 5 percent of financial assets to a separate trading account funded from current savings above emergency needs.

- Profit transfers. Each quarter, transfer 50 percent of profits above the prior high-water mark to the long-term core. The remainder stays in the sleeve to compound.

- Loss limits. If the sleeve falls 30 percent from its high-water mark, reduce exposure to a minimal level and pause new trades for a month. No re-seeding during the pause.

- No bailouts. The emergency fund and retirement accounts are off limits for margin calls.

The effect is that the trading sleeve can add to long-term assets when successful, yet cannot compromise near-term stability or retirement compounding if it struggles.

Retiree Managing Distributions

Now consider a retiree drawing planned distributions from a diversified portfolio. Liquidity for withdrawals is scheduled, and risk tolerance for additional variability is low. A small trading sleeve can still exist, but rules differ:

- Seed and size. Limit the trading sleeve to 1 percent to 2 percent of investable assets.

- Profit transfers. Monthly or quarterly, move any profits above the high-water mark to the core to support overall plan stability.

- Loss containment. If the sleeve declines by 10 percent, scale risk to near cash. Re-seeding is prohibited for twelve months.

- Distribution safeguarding. The liquidity ladder for required distributions is completely separate and cannot be tapped for trading collateral.

Here the policy prioritizes capital preservation and spending reliability. The trading sleeve functions as a capped, experimental allocation whose gains are quickly harvested and whose losses are quickly contained.

Entrepreneur with Variable Income

Finally, consider an entrepreneur with irregular cash flows. Business risk is already significant. The trading sleeve’s role is modest and tightly controlled, both to prevent correlation with business fortunes and to keep liquidity flexible:

- Seed and size. Seed the sleeve with a fixed dollar amount that represents a small fraction of surplus liquidity. Size does not scale automatically with business success.

- Profit path. When profits exceed a threshold, sweep most of them to a safe reserve that supports business volatility, not to the trading sleeve.

- Stress rule. If business conditions deteriorate below preset metrics, suspend trading until conditions stabilize, regardless of sleeve performance.

- Custody separation. Keep the sleeve at a broker distinct from both personal long-term accounts and business accounts to avoid intermingling risk.

In this context, the funding policy explicitly acknowledges non-portfolio risks and limits the chance that trading amplifies them.

Stress Testing the Structure

Stress testing does not require complex models. The key is to assess whether the trading sleeve can fail completely without endangering essential goals.

- Joint drawdown. Assume a severe equity market decline at the same time the trading sleeve experiences its worst recent drawdown. Would total losses remain within tolerance

- Liquidity shock. Assume a margin call during an illiquid period. Does the sleeve have enough internally generated liquidity to meet calls without tapping the core

- Correlation spike. In crises, correlations can move toward one. If the trading sleeve relies on diversification across instruments, can it withstand a temporary correlation surge

- Operational error. Consider a scenario of order entry mistakes or a technology outage. Are position limits and kill switches in place to cap damage

By designing funding rules that pass these tests, the portfolio can absorb unfavorable paths with less disruption.

Performance Evaluation and Attribution

Segregation allows performance to be measured fairly. A trading sleeve should be evaluated on capital actually allocated to it and on risk actually taken.

- Return on allocated capital. Express returns relative to the equity in the sleeve, not the total portfolio.

- Risk-adjusted metrics. Track drawdown, volatility, and the relationship between gains and losses. Compare realized risk to the policy’s assumptions.

- Attribution and exposure. Decompose results into market exposure, factor tilts, and idiosyncratic contributions. This helps determine whether transfer rules are appropriate.

- Transfer impact. Evaluate how profit skimming and drawdown controls affect both the sleeve and the core. Effective policies should show a pattern of profits migrating to the core while losses remain contained.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Creeping exposure. Allowing the trading sleeve to grow unchecked during good periods can create outsized risk later. Profit skimming and caps address this.

- Core bailouts. Funding margin calls from long-term capital undermines the entire separation. Establish non-recourse rules.

- Hidden leverage. Complex instruments can embed leverage and financing costs that escalate risk in stress. Use explicit leverage limits and monitor utilization.

- Liquidity mismatch. Trading illiquid assets with short-dated liabilities can force poor exits. Maintain a sleeve-level liquidity buffer.

- Tax churn. High turnover without attention to tax mechanics can reduce net results. Recognize jurisdictional rules and frictions.

- Reporting gaps. Without regular, transparent reporting, drift occurs. Set a cadence and stick to it.

Implementation Checklist

- State the purpose of the trading sleeve in one or two sentences.

- Define initial size, maximum allowable size, and maximum dollar loss tolerance.

- Specify leverage and instrument limits, including margin utilization caps.

- Establish profit skimming thresholds, cadence, and high-water mark rules.

- Define drawdown triggers and actions, including pause protocols and re-seeding rules.

- Separate custody and ensure no cross-collateralization with long-term accounts.

- Set a reporting schedule and the metrics to track.

- Document tax and operational constraints relevant to the sleeve.

- Predefine stress scenarios and required responses.

Conclusion

Funding trading accounts is a structural choice that shapes the resilience of the entire portfolio. A clear policy defines size, sources, transfer rules, and guardrails. When the trading sleeve is ring-fenced and governed with measurable rules, it can seek incremental return without threatening the compounding core. The separation also improves behavior under pressure and produces cleaner performance evaluation. The emphasis is not on predicting outcomes but on designing a system that can accommodate a wide range of outcomes while keeping long-term objectives intact.

Key Takeaways

- Funding trading accounts is a governance decision that separates higher-volatility activity from long-term compounding capital.

- Clear flow rules for seeding, profit skimming, and re-seeding prevent size creep and protect the core portfolio.

- Allocation size should reflect dollar loss tolerance, joint stress with core assets, and behavioral capacity, not hoped-for returns.

- Operational details such as custody, margin, liquidity buffers, and tax frictions can make or break the funding policy.

- Regular measurement, stress testing, and adherence to predefined triggers sustain discipline and resilience over time.