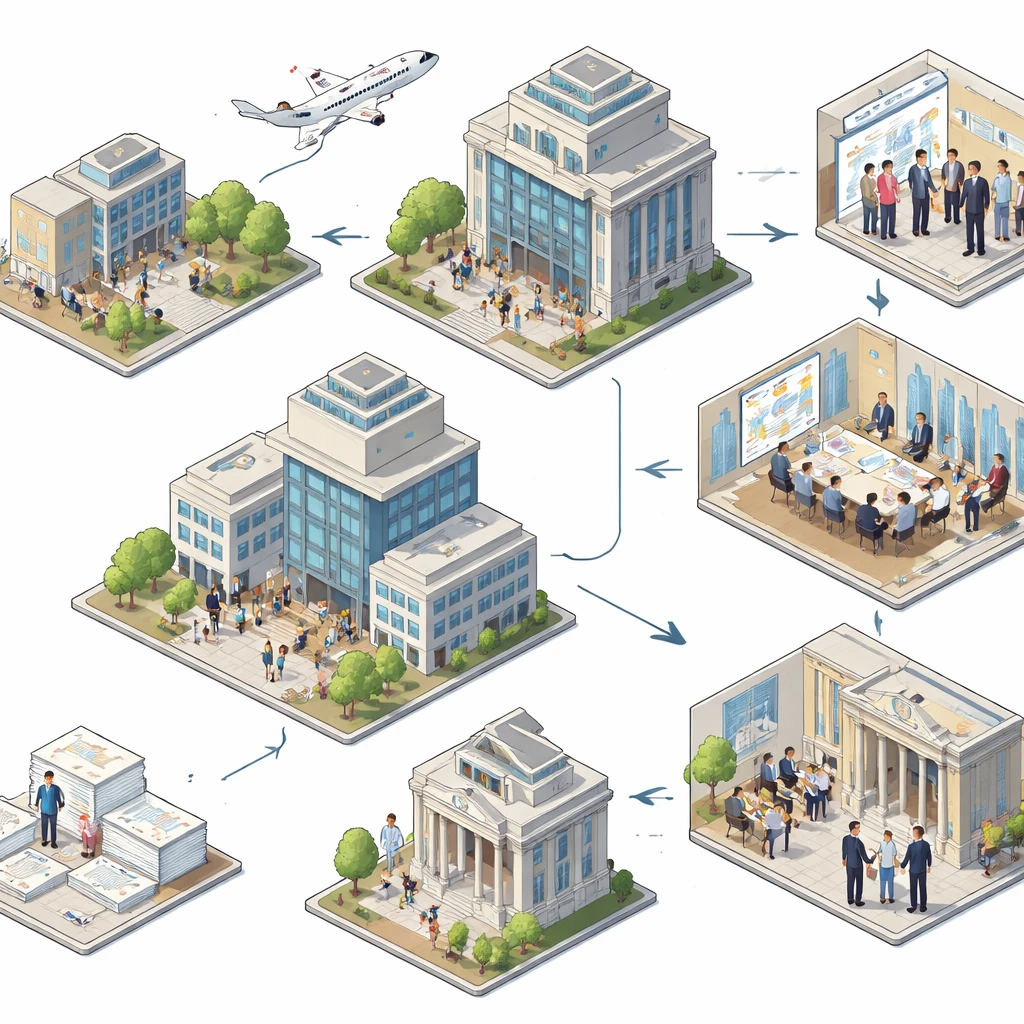

The lifecycle of a public company describes the typical sequence of stages a corporation passes through as it moves from private formation to listing on a stock exchange, then matures, adapts, and eventually restructures or exits the public markets. The lifecycle perspective does not claim that every firm follows the same path. It provides a framework that links corporate finance choices, disclosure duties, and market structure into an integrated picture of how public companies operate over time.

What Is the Lifecycle of a Public Company

A public company is one whose equity is broadly available to investors through organized markets such as stock exchanges. The lifecycle begins with private formation and early financing, proceeds through a transition to public status, and continues with the responsibilities and opportunities of life as a listed issuer. Over time, companies may change their capital structures, investor bases, and strategic footprints. Some firms remain public for decades. Others are acquired, taken private, reorganized, or liquidated.

This concept fits within the broader market structure because public equity markets are the primary venue for large scale capital formation, price discovery, and ownership transfer. Primary offerings provide capital to issuers. Secondary trading provides liquidity to investors and continuous valuation signals to managers and boards. Regulation, exchange rules, and the actions of intermediaries such as underwriters, auditors, and index providers shape the environment at each stage.

Why the Lifecycle Exists

The lifecycle exists because the needs of a growing enterprise differ from the needs of a mature enterprise. Early in life, firms seek capital and legitimacy. Later, they seek scale, efficiency, and stability. Public markets offer access to large pools of capital, a mechanism for valuing and transferring ownership, and an accountability structure provided by mandatory disclosure and shareholder oversight. Over time, the same transparency and liquidity that support growth can expose strategic or financial weaknesses, prompting restructuring or exit. The lifecycle is therefore a reflection of both financing needs and governance dynamics.

Stage 1: Formation and Private Growth

Most companies begin as private entities funded by founders, friends and family, angel investors, or venture and private equity funds. Capital raising is negotiated directly with investors. Disclosure is limited to what counterparties require. Boards are small and highly involved in operations. The focus is on building a product, establishing market fit, and creating processes that can be scaled.

During this stage, companies often use preferred equity with protective provisions, structured board rights, and milestone based financing. Financial reporting is produced for internal management and investors but is not publicly distributed. Governance is pragmatic and centered on speed. Employee equity grants are common, but liquidity is scarce. Employees and early investors typically cannot sell freely and must wait for a liquidity event such as a public listing or acquisition.

Stage 2: Preparing to Go Public

As scale and capital needs increase, some firms consider becoming public. The decision is not merely financial. It also involves governance, operational readiness, and tolerance for ongoing scrutiny. Preparation often includes:

- Financial controls and audits. Public companies must produce audited financial statements under applicable standards and maintain internal control frameworks.

- Disclosure systems. Management must be able to produce timely, accurate filings, earnings releases, and investor communications consistent with regulations such as Regulation FD in the United States.

- Board composition. Listing rules usually require independent directors and specific committees such as audit, compensation, and nomination or governance.

- Legal restructuring. Some firms reorganize their corporate structure, create holding companies, or redomicile to align with regulatory and tax considerations.

Motivations to list commonly include access to equity capital for growth, liquidity for existing shareholders, a currency to use in acquisitions, and public visibility that can aid hiring and partnerships. Costs include underwriting fees for certain listing paths, ongoing compliance expenditures, and the management time required for investor relations and reporting.

Stage 3: Pathways to the Public Market

There are multiple routes to becoming publicly traded. Each path reflects different tradeoffs among price discovery, cost, and control of the process.

Initial Public Offering

In a traditional IPO, the company files a registration statement with the securities regulator, such as an S-1 in the United States. Underwriters form a syndicate, conduct due diligence, and market the offering to institutional investors during a roadshow. The offering price is set following investor feedback. In a firm commitment IPO, underwriters purchase the shares from the company and resell them to investors. A best efforts IPO leaves placement risk with the issuer.

Many IPOs include an overallotment option, commonly called a greenshoe. This allows underwriters to sell more shares than initially offered and then stabilize trading by purchasing in the market or exercising the option. Early shareholders are typically subject to a lock-up period that restricts sales for a defined time following the offering. When that period ends, trading volume often increases as additional shares become freely tradable.

Auction Based IPOs

Some issuers have used auctions to supplement or replace bookbuilding. In a Dutch auction variant, investors submit bids specifying quantity and price. The clearing price where supply meets demand becomes the offer price for all successful bidders. The approach attempts to broaden participation and rely more on transparent price discovery. It has been used less frequently than traditional bookbuilding because issuers and underwriters often prefer the control and relationship benefits of conventional marketing.

Direct Listings

In a direct listing, existing shareholders sell their shares directly on the exchange without a new capital raise by the company. No underwriter purchases shares from the issuer. The exchange sets a reference price to start trading, and price discovery occurs in the market. Direct listings can offer liquidity without dilution and may reduce issuance fees, but they rely on the market to absorb supply without the stabilization practices used in many IPOs. Some jurisdictions now permit companies to raise primary capital in a direct listing, which blends elements of the two approaches.

Special Purpose Acquisition Companies

SPACs are publicly listed shells that raise capital to acquire a private company within a defined period. When a SPAC identifies a target, shareholders vote on the merger and often have redemption rights. The private target becomes public through the merger. SPACs can provide speed and deal certainty compared with some IPOs, though they introduce complexity such as sponsor incentives, warrant structures, and shareholder redemptions that affect the final capital raised.

Stage 4: The Listing Event

The listing event marks the transition from primary issuance to secondary market trading. On the first day of trading, market makers coordinate order flow to establish an opening price. Liquidity can be uneven early on as investors refine valuations. The issuer begins life as a listed company with a new set of ongoing obligations.

Analyst coverage often develops after the quiet period ends. Analyst models and industry reports influence how the market frames the company’s growth, margins, and competitive position. Inclusion in major indices may follow once eligibility criteria are satisfied, which can affect ownership as index funds adjust holdings. The mechanical nature of index reconstitution can cause short term trading volume spikes, but the underlying inclusion typically reflects size, liquidity, or other defined attributes.

Stage 5: Ongoing Public Company Duties

Once public, a company operates under a continuous disclosure regime. Core elements include:

- Periodic reporting. Annual and quarterly financial statements, management discussion, and risk updates. Foreign private issuers follow jurisdiction specific schedules, such as Form 20-F in the United States.

- Current reporting. Material events are disclosed promptly through current reports. Examples include significant acquisitions, leadership changes, or major financing transactions.

- Insider trading controls. Policies restrict trading during blackout windows and require timely reporting of insider transactions.

- Shareholder meetings and proxies. Annual meetings, election of directors, and advisory votes on executive compensation. Proxy statements provide detailed compensation and governance information.

- Regulatory compliance. Maintenance of internal controls over financial reporting and adherence to exchange listing standards.

The cadence of quarterly reporting influences internal planning and communication. Many firms provide guidance on selected metrics, though guidance practices vary by industry and strategy. Investor relations functions translate corporate performance into accessible information and interact with analysts, institutions, and retail investors within fair disclosure rules.

Stage 6: Capital Allocation as a Public Company

Public status expands the financing toolkit. Management and the board decide how to fund operations, pursue growth, and return capital, subject to constraints from investment opportunities, balance sheet strength, and investor expectations.

- Follow on equity offerings. Primary offerings raise new capital for the company. Secondary offerings sell shares held by existing investors. Shelf registrations and at the market programs can provide flexibility to issue over time.

- Debt financing. Listed companies often gain access to larger and more diverse debt markets. Options include unsecured notes, secured loans, and convertible bonds. Credit ratings can influence pricing and investor access.

- Share repurchases and dividends. Boards may authorize repurchases or distributions subject to legal and liquidity constraints. Repurchases can be executed through open market programs or structured mechanisms. Rule 10b5-1 plans are often used to manage trading windows and reduce allegations of informational advantage.

- Stock as acquisition currency. Public equity can be used to acquire other companies, which spreads ownership and affects post merger integration and control.

These choices alter the share count, leverage, and risk profile. They also influence which investor segments hold the stock. For example, some income oriented funds focus on dividend paying issuers, while growth focused investors may emphasize reinvestment opportunities. Public companies navigate these preferences while pursuing their strategic plans.

Stage 7: Strategic Reshaping and Governance Evolution

As market conditions and corporate goals evolve, public companies often reshape their structure.

- Spin offs and carve outs. A spin off distributes shares of a subsidiary to existing shareholders, creating a separate public company. A carve out sells a minority stake in a subsidiary through an IPO. Both aim to clarify valuations or tailor capital structures to differing business profiles.

- Tracking stock. Some issuers create a class of stock that tracks the performance of a specific division without full legal separation. This approach can highlight growth assets while maintaining control, though it introduces complexity in governance and capital allocation.

- Dual class share structures. Certain companies list with multiple share classes to concentrate voting power. Listing rules may require sunset provisions or other protections. Over time, investor pressure and index eligibility criteria can shape how these structures persist.

- Shareholder engagement and activism. Public companies interact with a diverse investor base. Engagement ranges from routine outreach to contested proxy votes over strategy, board composition, or capital use. The process operates within securities law and exchange rules.

Governance decisions influence access to capital and the stability of the shareholder base. For instance, improved disclosure and board independence can broaden the set of institutions willing to hold the stock.

Stage 8: Maturity, Plateau, and Renewal

At maturity, growth often moderates and margins may stabilize. Decision making shifts toward efficiency, cost discipline, and predictability. Companies at this stage frequently evaluate regular dividends, structured repurchase programs, and selective acquisitions. Scale can provide bargaining power and resilience, but it can also slow innovation. Some firms pursue renewal through research and development, business model shifts, or transformative mergers.

Examples help illustrate the diversity of paths. A consumer goods firm might mature into a stable cash generator with steady payouts. A software platform might reinvent its revenue model by migrating to subscriptions, which can reset growth and valuation dynamics. A regulated utility may remain mature for long periods because its returns are shaped by regulatory frameworks rather than rapid market expansion.

Stage 9: Stress, Restructuring, and Delisting Risk

Not all trajectories are upward. Competitive shocks, technological change, macroeconomic downturns, or leverage can create stress. Warning signs often include declining margins, covenant pressure, auditor going concern notes, or noncompliance with exchange rules such as minimum price or market capitalization thresholds.

Boards may consider restructuring tools such as asset sales, debt exchanges, cost reductions, and leadership changes. Reverse stock splits are sometimes used to regain compliance with price based listing standards. If liquidity and solvency pressures intensify, companies may seek court supervised reorganization. In jurisdictions with Chapter 11 style processes, public equity can be significantly diluted or canceled as new capital providers fund the restructuring. Some companies emerge and relist after reorganization, but outcomes vary widely.

Stage 10: Exit From the Public Markets

Public companies can exit the listed environment in several ways.

- Take private transactions. A financial sponsor or strategic buyer acquires the company and delists it. The process includes a board review, fairness opinions, regulatory approvals, and a shareholder vote. Post closing, ownership is concentrated, disclosure obligations are reduced, and restructuring can proceed outside the quarterly reporting cycle.

- Acquisition by another public company. A stock or cash merger results in the target’s shares being converted into consideration and delisted. Combined companies may realize scale benefits, new markets, or cost synergies, subject to integration execution.

- Liquidation. When ongoing business is no longer viable and sale options are limited, a company may wind down, sell assets, and distribute residual value according to the capital structure’s priority.

Exit is not always permanent. Firms that are taken private sometimes return to public markets after operational changes, a revised capital structure, or a strategic pivot. Others remain private because their financing needs can be met without public listing.

How the Lifecycle Fits the Market Structure

Understanding the lifecycle clarifies how primary and secondary markets interact. Primary issuance provides capital to the company at formation, at IPO, and during follow on offerings. Secondary trading allows investors to buy and sell with liquidity, which supports price discovery and portfolio management. Intermediaries perform distinct roles at each stage:

- Underwriters and exchanges. Facilitate listing, liquidity, and initial price formation.

- Auditors and rating agencies. Provide assurance on financial reporting and credit quality.

- Index providers and custodians. Shape ownership through eligibility standards and operational infrastructure.

- Sell side research and buy side institutions. Interpret information and allocate capital based on mandates and risk tolerance.

Regulators set disclosure and conduct standards. Their rules influence incentives, such as when safe harbors allow companies to repurchase shares or provide forward looking information. This institutional framework is part of what defines each stage of the lifecycle.

Real World Context and Examples

Real companies illustrate the variety of paths within the same framework. Consider three well known cases:

- Alphabet’s Dutch auction IPO in 2004. The company used an auction method to allocate shares, aiming to reduce underpricing and broaden access. The auction set a clearing price that applied to all successful bidders. After listing, Alphabet transitioned into a more traditional public company cadence with quarterly results, acquisitions, and the development of a dual class structure that concentrated voting control.

- Spotify’s direct listing in 2018. Existing shareholders sold into the public market without a traditional underwritten offering. The exchange published a reference price, and trading began based on supply and demand. The approach provided liquidity without issuing new shares at the outset. Spotify later used the public markets for ongoing disclosure and investor engagement rather than for large immediate capital raises.

- SPAC combinations in 2020 and 2021. A surge in SPAC activity brought a range of private companies to market. Outcomes were mixed. Some firms achieved the desired capital raise and listing, while others experienced heavy redemptions, capital shortfalls, or post merger volatility. The episode shows how a particular pathway can expand access to the public markets, yet still subjects the resulting public entities to the same disclosure and accountability environment as traditional IPOs.

Turnarounds and exits also provide context. Dell’s take private transaction in 2013 demonstrated how a mature public company can pursue strategic changes as a private entity and later reengage with public markets through a different structure. Conversely, cases such as Blockbuster’s decline illustrate how technology shifts can push public firms through restructuring and liquidation despite brand recognition and historical scale.

What Changes Across the Lifecycle

Several dimensions evolve as a company moves through the stages.

- Disclosure intensity. Private companies share information with a small set of investors. Public companies follow detailed reporting rules and face scrutiny from analysts and the media.

- Ownership dispersion. Early ownership is concentrated among founders and early investors. Public listing spreads ownership across institutions and individuals, which changes incentives and governance dynamics.

- Cost of capital and flexibility. Access to public markets can reduce the cost of capital and increase financing options. At the same time, quarterly reporting and market expectations can constrain timing and presentation of strategic moves.

- Governance and accountability. Board independence, committee structures, and shareholder rights become more formalized. Voting outcomes and engagement can influence executive compensation, sustainability reporting, and strategic directions.

- Operational cadence. The rhythm of earnings cycles, guidance, and investor relations becomes part of management practice. Forecast errors, whether positive or negative, can have visible share price effects, which may influence communication policies.

Practical Illustrations

Short examples can make the stages concrete:

- Private to public readiness. A medical device startup approaching regulatory approval might invest heavily in quality systems, clinical data management, and audit readiness long before it files to go public. Preparing these systems reduces listing risk and strengthens credibility with potential investors.

- IPO lock up expiration. A software company that sold 15 percent of its shares in an IPO may face a large increase in float when the 180 day lock up ends. Trading volume often rises as employees and early investors gain the ability to sell, and the investor base can broaden.

- Follow on offering for growth. A logistics firm with expanding demand could issue a secondary offering to fund new distribution centers. The new capital supports capacity, while the increased float enhances liquidity for all investors.

- Spin off to sharpen focus. A diversified industrial might spin off a faster growing automation unit. Two public companies result, each with a clearer strategy and tailored capital structure, which can change the set of analysts and investors who follow each entity.

- Compliance challenge. A retailer whose share price falls below its exchange’s minimum bid requirement may implement a reverse split to regain compliance while it works on operational changes. Failure to meet listing standards can lead to delisting and reduced liquidity on over the counter venues.

Global and Cross Listing Considerations

Public company lifecycles also vary across jurisdictions. Foreign private issuers in the United States file annual reports on Form 20-F and may follow home country governance practices within defined limits. Companies can cross list to broaden investor access, increase liquidity, or signal governance quality. American depositary receipts and similar instruments allow trading of non domestic shares on local exchanges. Cross listings introduce additional disclosure coordination, currency considerations, and sometimes differing shareholder rights frameworks.

Some firms change their primary listing venue as strategic priorities evolve. Moving between exchanges can affect analyst coverage, index eligibility, and ownership composition. These moves are shaped by regulatory cost, depth of local capital markets, and the geographic distribution of customers and suppliers.

Why the Lifecycle Matters for Market Participants

The lifecycle lens helps clarify how supply and demand for shares evolve, how disclosure shapes expectations, and how governance mechanisms interact with strategy. For example, understanding lock up schedules and index eligibility criteria explains changes in free float and potential shifts in the investor base. Recognizing the tools of capital allocation helps explain changes in leverage, share count, and payout policies over time. For policymakers and exchanges, the lifecycle highlights the balance between facilitating capital formation and enforcing investor protection.

For corporate managers and boards, the lifecycle underscores that listing is not an endpoint. It is a structural change that brings access to capital and public discipline, followed by a sequence of choices about capital structure, governance, and strategy. For investors and researchers, the lifecycle provides an organizing framework for comparing firms at different stages without assuming that outcomes will resemble those of any particular example.

Limits of the Lifecycle Framework

No model captures the diversity of real firms. Some companies remain private for long periods because private capital is sufficient. Others list earlier due to regulatory or strategic reasons. Sector characteristics matter. Biotech companies often list before profitability because clinical development requires significant capital and public investors understand trial risk. Regulated utilities may remain public for decades with stable cash flows and dividends. Platform technology companies may use dual class structures to preserve long term control. The lifecycle framework should be used to describe patterns, not to predict a specific company’s path.

Concluding Perspective

The lifecycle of a public company connects corporate finance, market structure, and governance. It begins with private formation, accelerates at the moment of listing, and unfolds through capital allocation, strategic reshaping, and eventual renewal or exit. The same system that enables rapid growth also enforces accountability through disclosure and market scrutiny. Understanding this progression improves the ability to interpret corporate actions, regulatory developments, and the flow of ownership through time.

Key Takeaways

- The public company lifecycle links financing needs, disclosure, governance, and market structure from formation to possible exit.

- Listing pathways include IPOs, auctions, direct listings, and SPAC mergers, each with distinct tradeoffs in cost, control, and price discovery.

- After listing, periodic and current reporting, board independence, and investor engagement define the operating environment.

- Capital allocation tools such as follow on offerings, debt, repurchases, dividends, and stock financed acquisitions shape ownership and risk.

- Outcomes range from long term maturity to restructuring or exit, with sector characteristics and strategic choices driving the path.