Options are contracts that grant a right, not an obligation, to buy or sell an underlying asset at a specified price before or at a stated expiration. They are designed to shift risk, to create payoffs that depend on particular future states of the world, and to help markets discover information about uncertainty. The question of why options exist is not about tactics or speculation. It is about the economic role these contracts play within the broader market structure and the practical needs they serve in commerce and finance.

Defining the Core Idea: Why Options Exist

Options exist because many economic agents value insurance-like protection and tailored exposure that ordinary spot or forward contracts cannot provide. A forward contract obligates both parties, while an option binds only the seller and leaves the buyer with choice. That choice has value whenever future outcomes are uncertain and different states of the world produce very different tradeoffs between costs and benefits.

By paying a known premium upfront, one party can secure the ability to act only if conditions become unfavorable or favorable, depending on the type of option. The seller receives the premium and commits to perform if the buyer exercises. This structure allows risks related to price levels, volatility, and timing to be redistributed to those more willing or better able to bear them.

In formal economic terms, options create state-contingent claims. A payoff that activates only in certain states, such as when a price falls below a threshold or rises above it, enlarges the set of outcomes that can be financed and insured. This property is central to the idea of completing markets. When markets are more complete, agents can shape exposures more precisely, which supports investment planning, inventory management, and balance sheet stability.

Historical and Institutional Context

Contingent claims are not new. Historical accounts describe option-like arrangements in agriculture and commerce. Modern listed options markets developed in the early 1970s as exchanges standardized contracts and central clearing reduced counterparty risk. The ability to quote and manage option values benefited from advances in option pricing theory, which clarified how volatility, time, and interest rates drive premiums. Standardized terms for expiration dates, strike prices, contract sizes, and settlement procedures made options accessible to a wide range of institutions.

Today, listed options trade on exchanges with a central counterparty clearinghouse that novates each trade, becoming the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer. Margin requirements, daily settlement, and risk-based capital rules are designed to contain counterparty risk. Alongside listed markets, a large over-the-counter market supports bespoke option contracts tailored to specific needs, such as unusual settlement schedules or custom-defined triggers.

How Options Fit Into the Broader Market Structure

Options sit alongside spot markets, futures, forwards, and cash-and-carry financing. They link tightly with these markets through no-arbitrage relationships. A simple example is the relationship among a call, a put, the underlying asset, the strike, and interest rates, often summarized as put-call parity. The exact formula is not needed here. What matters is that options are not isolated instruments. Their prices and risks are intertwined with the prices and risks of the underlying asset and related derivatives.

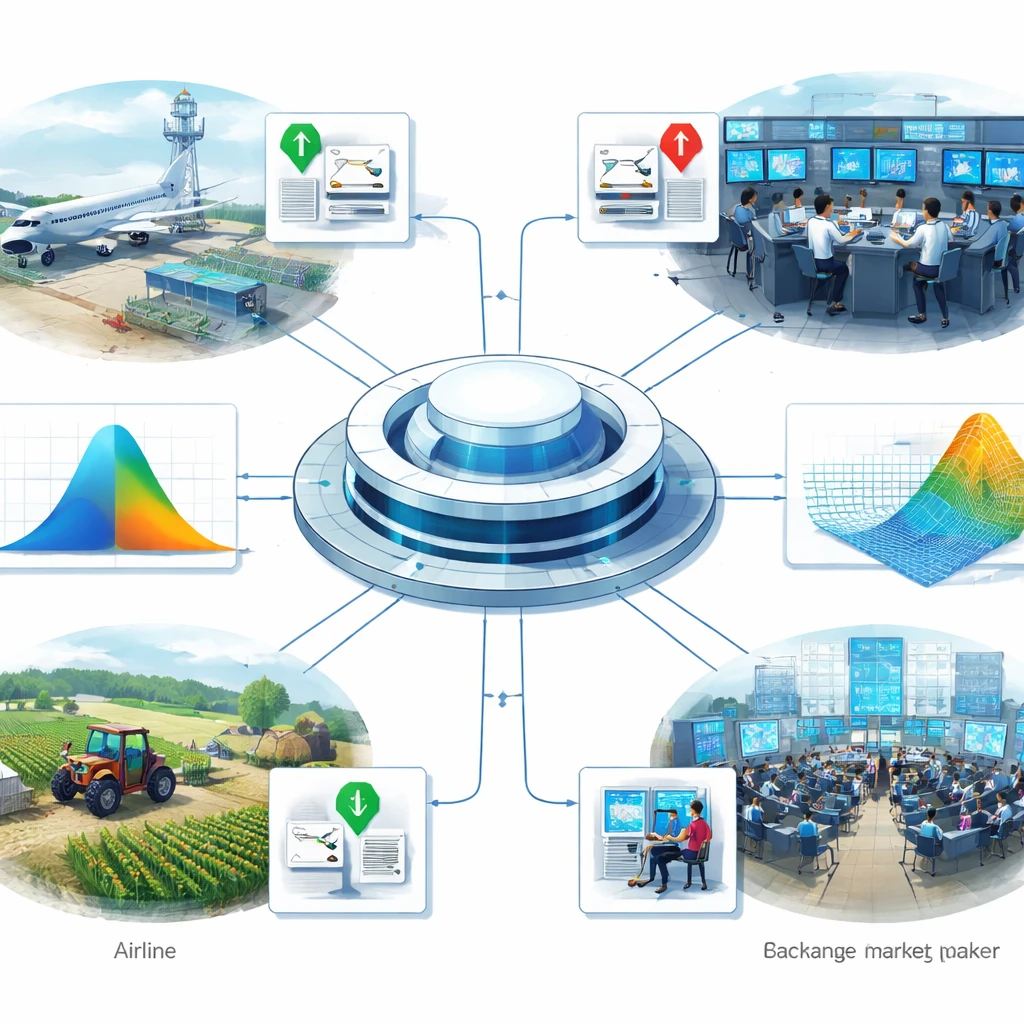

Several types of participants interact in options markets:

- Hedgers who seek to manage exposures that arise from business operations or portfolios.

- Investors who are willing to take on specific contingent risks for a premium.

- Market makers who provide continuous bids and offers, and hedge their inventories in the underlying or related derivatives.

- Arbitrageurs who enforce basic price relationships across markets, which helps align option prices with the underlying.

Exchanges and clearinghouses provide the infrastructure that keeps this ecosystem operational. Exchanges enforce listing standards and trading protocols. Clearinghouses set initial and variation margin, monitor risk, and reduce the chance that a default by one party destabilizes others. The combination of standardized contracts, transparent quotes, and central clearing helps produce consistent pricing and deeper liquidity.

Risk Transfer and the Insurance Analogy

One of the most intuitive reasons options exist is the need for insurance against unfavorable price moves. Insurance is valuable when losses are concentrated in certain states of the world. A put option on a commodity or security can mitigate losses if prices fall below a chosen level. The buyer sacrifices the upfront premium to eliminate large adverse outcomes. The seller accepts the possibility of loss in that downside state in exchange for the premium and the chance that the option expires unused.

Consider an airline with significant jet fuel consumption. Its costs rise when oil prices increase. A contract that provides the right to purchase fuel inputs at a ceiling price is valuable because it caps a critical cost that could otherwise destabilize the business. The airline does not need to commit to purchase under every scenario. It needs the right to purchase if spot prices spike. That is an option-like need, and it is why energy options are widely used in commercial hedging programs.

A grain producer faces the opposite problem. Low prices can reduce revenue below break-even. A right to sell at a floor price can protect cash flows during harvest season when supply surges can depress markets. Again, the key is conditionality. The producer accepts paying a premium so that protection activates exactly in the states where it matters most.

These examples show why options persist. They allow users to exchange a known, limited cost for protection against severe outcomes. That exchange supports planning and financing, because creditors and investors can evaluate worst-case scenarios more confidently when protection is in place.

Tailoring Payoffs and Completing Markets

Options are building blocks for shaping non-linear payoffs. A non-linear payoff does not change one-for-one with the underlying price. It may flatten losses beyond a threshold or reduce gains above a cap. In many business contexts, marginal utility of cash flows is not constant. The first units of protection or revenue may be crucial for solvency, while additional gains matter less. Options make it possible to match payoff shapes to these preferences.

From a theoretical perspective, a combination of basic options can approximate a wide range of contingent payoffs. That insight explains why options are central to completing markets. If only spot or forward contracts were available, many economically relevant risks would remain unhedged. Non-linear payoffs are also important for regulatory and accounting constraints. Some institutions face capital charges that depend on worst-case losses rather than average outcomes. Options can bound those losses within defined limits, which aligns risk exposures with policy constraints.

Crucially, the existence of options does not imply that every investor should use them. The rationale is broader. Society benefits when those who especially need protection can obtain it from those who are willing to provide it. Prices arise from the intersection of these needs, the supply of capital for risk bearing, and the information embedded in markets about future uncertainty.

Embedded Options in Everyday Finance

Options are not confined to exchange-traded contracts. They are embedded in many ordinary financial arrangements:

- A callable bond gives the issuer the right to redeem early when interest rates fall, which resembles the issuer owning a call on its own debt.

- A convertible bond gives the holder the right to exchange debt for equity, which embeds a call on the issuing company’s stock.

- A residential mortgage often allows the borrower to prepay without penalty, which functions as a call option on the loan when rates drop.

- Warrants and employee stock options grant rights to acquire shares at specified prices, which can align incentives and support compensation structures.

- Rights of first refusal in real estate or supplier contracts confer the right to transact on predefined terms if certain events occur.

These examples show that option-like features are intertwined with financing, compensation, and corporate policy. Recognizing the option component clarifies value and risk. For instance, the cost of a callable bond to investors depends on the chance that the issuer will call when it is optimal to do so. Understanding the embedded option helps explain pricing and the behavior of issuers and holders when conditions change.

Price Discovery and Information in Option Markets

Options contribute to price discovery in a way that complements the underlying market. Underlying prices capture the market’s best estimate of expected value. Option prices encode information about the distribution of future outcomes around that expectation, including dispersion and skewness. A common practice is to translate option prices into implied volatility, which is the level of volatility that would be consistent with observed premiums under a chosen valuation model.

Implied volatility surfaces vary by strike and maturity. Differences across strikes reflect how the market assesses tail risk. For broad equity indexes, it is common to observe higher implied volatility for options that protect against large declines, a pattern sometimes called skew. When market participants are especially concerned about downside scenarios, the relative price of downside protection tends to rise. Conversely, in periods of calm, implied volatility often compresses across strikes, reflecting a narrower distribution of expected outcomes.

For corporate issuers and risk managers, the information content of option prices is useful. It offers a market-based measure of perceived uncertainty that can inform budgeting, capital allocation, and contingency planning. For regulators and policymakers, implied volatility and skew can signal stress in specific sectors or across the financial system.

Intermediation, Liquidity, and Clearing

Options exist within a specialized microstructure that makes continuous trading possible. Market makers post two-sided quotes and adjust prices as order flow and volatility evolve. They typically offset inventory risk in related instruments, which ties the option market to the underlying market. This hedging activity aligns prices and helps ensure that large orders can be executed without extreme dislocations.

Clearinghouses perform a foundational role. When an option trade is executed, the clearinghouse becomes the counterparty to both sides through novation. This arrangement standardizes credit risk and reduces the need for bilateral credit assessment among thousands of market participants. Margin requirements are calibrated to potential future exposure based on price history and models of volatility. Variation margin is collected and paid daily, which keeps cumulative losses from building unnoticed. These mechanisms are essential for the long-run viability of options markets.

Why Options Are Economically Sustainable

Options persist because they solve problems that recur in many contexts. Several characteristics make them durable within the financial system:

- They provide selective protection that activates only when needed, which helps budget scarce hedging resources toward the most damaging scenarios.

- They enable the transfer of tail risk to capital providers who can diversify or price it appropriately.

- They offer standardized, legally enforceable terms that reduce negotiation time and transaction costs compared with bespoke contractual protections.

- They reveal information about uncertainty through prices that summarize many dispersed views.

- They integrate with existing instruments and institutions, which supports liquidity and reliable settlement.

Economic sustainability also reflects the balance of incentives. Option sellers charge premiums that compensate for expected losses in adverse states plus the cost of capital for committing to those states. Buyers pay those premiums when the benefit of protection or optional participation exceeds the cost. As long as both sides can evaluate and manage the associated risks, mutually beneficial trade is possible.

Constraints and Risks

The existence of options does not eliminate risk. It redistributes and transforms it. Several constraints shape how options are used and priced:

- Time decay reduces the value of optionality as expiration approaches if the underlying does not move sufficiently.

- Liquidity can vary by strike and maturity, which affects execution quality and the ability to enter or exit positions efficiently.

- Model risk arises when pricing and risk systems assume dynamics that fail in practice, for example during discontinuous price moves.

- Gap and jump risk are challenging because hedging often assumes smooth price changes. Large overnight events can create losses that exceed expectations based on normal fluctuations.

- Operational complexity can be nontrivial, especially for portfolios of options. Monitoring exposures such as delta, gamma, vega, and theta requires systems and controls.

These constraints are not reasons to avoid options. They are the cost side of the ledger that accompanies the benefits of selective protection and tailored exposure. Markets account for these costs through premiums, margin, and haircuts. Institutions account for them through policy limits, governance, and audit.

Real-World Contexts That Motivate Options

To see the practical motivation, consider a few settings where optionality is central:

Project evaluation. Firms often face irreversible investment decisions under uncertainty. The ability to delay, expand, or abandon a project resembles real options, which have option-like payoffs. Recognizing the value of deferral or flexibility can change which projects meet hurdle rates and how firms stage capital deployment.

Inventory and supply chain management. Producers and distributors manage demand uncertainty and input price volatility. Contracts that confer purchasing rights at predetermined prices allow operations to run without locking in quantities that may prove unnecessary. The economic role mirrors that of a call option on inputs.

Capital structure and corporate securities. Instruments such as convertibles and warrants help issuers balance interest costs with potential dilution. Investors who receive embedded options accept certain risks in exchange for the possibility of equity participation. The presence of optionality influences how securities trade and how issuers behave when market conditions shift.

Household finance. Mortgage borrowers in many jurisdictions can prepay, capturing value when rates decline. Lenders price this prepayment option by adjusting interest rates and by securitizing loans with attention to refinancing behavior. Insurance policies, mobile phone plans with upgrade rights, and subscription contracts with cancellation rights all contain option-like features that mirror the same economic principles.

Options, Expectations, and Market Discipline

Options help aggregate diverse expectations and risk preferences into observable prices. A market participant who believes that volatility is higher than implied by options can sell insurance-like protection in the underlying market and buy options, or pursue other combinations that align with their view. Another participant might do the opposite. The interaction of these views produces a market-clearing level of implied volatility and a structure of prices across strikes and maturities.

This process imposes discipline. If option prices become inconsistent with the underlying and with each other, arbitrageurs can construct offsetting portfolios that exploit the gap, bringing prices back into alignment. The existence of these relationships is one reason options are tightly integrated with overall market function. They are both a tool for managing uncertainty and a check on pricing coherence across markets.

Conceptual Relationship to Forwards and Insurance

It is often helpful to compare options with forwards and with insurance. A forward fixes a future transaction today, binding both parties. It removes uncertainty about the price but removes flexibility as well. Insurance pays when a loss event occurs, which is typically a well-defined state. An option is similar to insurance in that it has an upfront premium and activates in certain states, but it differs by allowing the buyer to choose whether to exercise based on observed prices. The flexibility to decide at the decision point, not at inception, is the distinguishing feature.

Because of this feature, options concentrate value near thresholds. When prices are comfortably away from the strike, the option behaves like a remote contingency. As prices approach the strike, the sensitivity of the option’s value to the underlying often increases. That behavior has important implications for risk management and for how market makers hedge. It is also a major reason why option markets provide useful signals about the distribution of outcomes rather than simply their average.

Why the Concept Endures

Options endure because uncertainty, asymmetric preferences, and constraints are persistent features of economic life. Businesses prefer to avoid severe downside events that threaten continuity. Households prefer to smooth consumption and secure major goals against shocks. Investors and specialized intermediaries are often willing to warehouse certain risks in exchange for compensation. Options organize these preferences into tradable contracts with clear rights and obligations, reliable settlement, and widely understood valuation principles.

When viewed this way, options are not primarily about aggression or leverage. They are about design. They help design payoffs that fit real objectives, design contracts that reduce bilateral credit risk through clearing, and design markets that reveal information about uncertainty every trading day.

Conclusion

Asking why options exist leads to a simple answer. They exist to make it feasible and efficient to transfer and reshape risk under uncertainty. The fine details of pricing and microstructure matter because they support that function at scale. The real-world examples matter because they show how optionality appears across business operations, financing choices, and household decisions. The institutional framework matters because it stabilizes a market where rights, obligations, and information are constantly in motion.

Key Takeaways

- Options exist to transfer and reshape risk through state-contingent payoffs that activate only in specified conditions.

- They fit into a larger market system that includes spot, forward, and futures markets, with exchanges and clearinghouses providing stability and transparency.

- Real-world uses include protection of input costs, revenue floors, and embedded rights in bonds, mortgages, and corporate securities.

- Option prices contribute to price discovery by revealing the market’s assessment of volatility and tail risk across strikes and maturities.

- The durability of options reflects their ability to complete markets, align incentives, and support planning under uncertainty.