Mutual funds and exchange-traded funds are the two dominant pooled vehicles in public markets. Both collect money from many investors and deploy it across a diversified portfolio according to a stated objective. They differ in how they are structured, how shares are created and redeemed, how investors transact, and how pricing and taxes work. Understanding these differences clarifies how each vehicle fits into the broader market system and why both persist side by side.

Foundations: Pooled Investment Vehicles in Market Structure

Pooled vehicles solve a fundamental problem for individuals and institutions. Building and managing a diversified portfolio security by security is costly and operationally demanding. Pooling capital delivers scale, lowers per-unit trading and administration costs, and centralizes professional portfolio management. It also creates standardized units that can be bought and sold with relative ease.

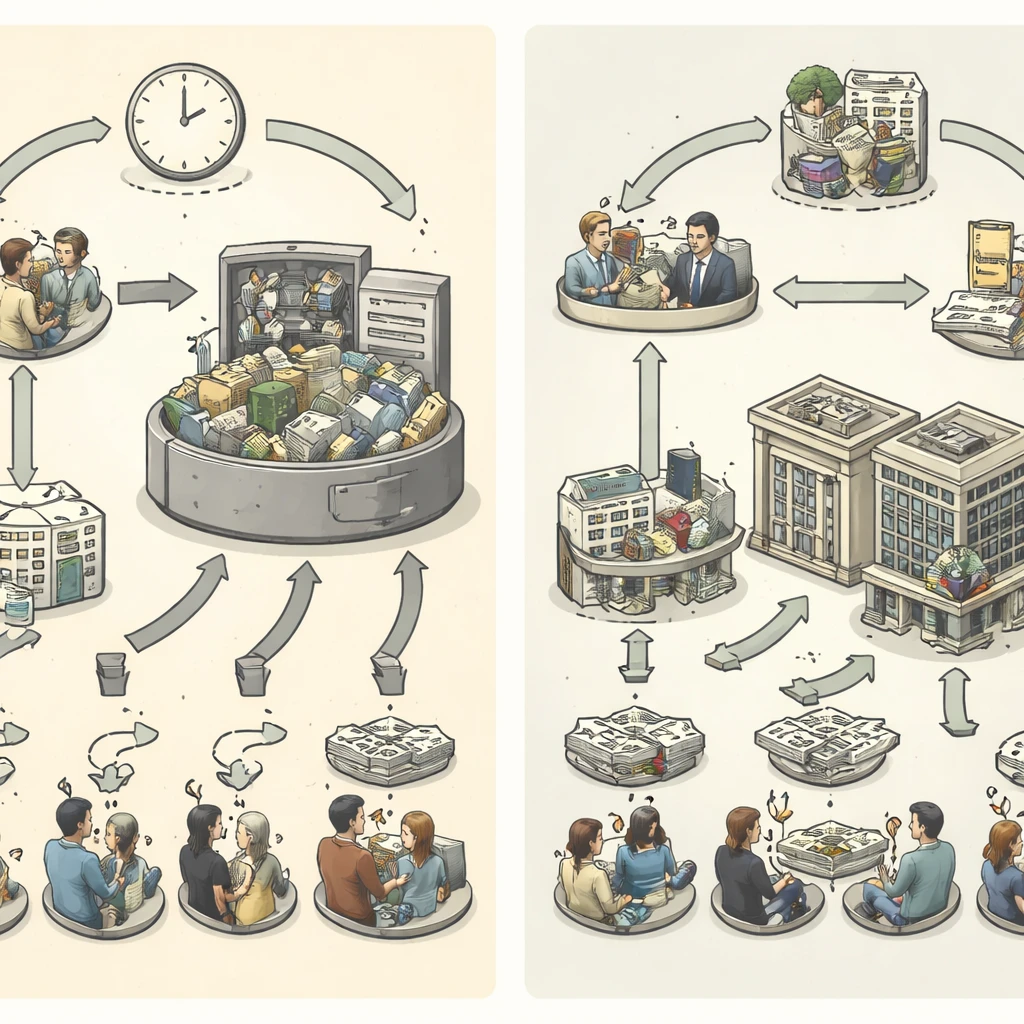

Within this broad category, mutual funds and exchange-traded funds organize ownership and trading differently. A mutual fund issues and redeems shares directly with investors at the fund’s net asset value, usually calculated after markets close each trading day. An ETF also holds a portfolio and calculates a net asset value, but its shares trade continuously on an exchange, with specialized intermediaries creating and redeeming shares in large blocks behind the scenes to keep market prices aligned with portfolio value.

What Is a Mutual Fund?

Legal structure and governance

Most mutual funds in the United States are registered investment companies under the Investment Company Act of 1940. They are typically organized as open-end funds, which means the fund stands ready to issue new shares or redeem existing shares at net asset value on any dealing day. The fund is overseen by a board of directors or trustees, has an adviser that manages the portfolio, and engages service providers such as a transfer agent, custodian, and administrator.

How mutual funds are priced and transacted

Mutual fund transactions occur at the end-of-day net asset value, commonly called NAV. Investors submit buy or sell orders during the day, and those orders receive the next computed NAV, a process known as forward pricing. The NAV is calculated by summing the market value of the fund’s holdings, adding income accruals, subtracting liabilities, and dividing by shares outstanding. For securities that do not trade late in the day or trade overseas, funds may use fair value pricing policies to estimate closing values, which can reduce dilution from market timing and improve equitable treatment among shareholders.

Because mutual fund transactions occur with the fund company rather than on an exchange, there is no intraday market price, no bid and ask spread for investors to negotiate, and no need to place limit or market orders. The trade settles once NAV is finalized, generally on the next business day in jurisdictions that have moved to a T+1 cycle.

Fees, share classes, and distributions

Mutual funds charge ongoing operating expenses, typically expressed as an annual expense ratio deducted from assets. Some funds also levy distribution and service fees, commonly called 12b-1 fees. Historically, many mutual funds offered multiple share classes with different fee structures, such as front-end load shares with a sales charge at purchase or back-end load shares with a contingent deferred sales charge when selling. Institutional share classes often carry lower expense ratios and may have higher minimum investment amounts. The modern trend has been toward lower-cost share classes and reduced prominence of sales loads.

Mutual funds distribute income and realized capital gains to shareholders, generally at least annually. Dividend and interest distributions reflect the income generated by the underlying portfolio. Capital gains distributions arise when the fund sells securities at a profit and does not have losses or inflows sufficient to offset those gains. Shareholders may elect to receive cash or to reinvest distributions into additional fund shares at NAV.

Transparency and reporting

Mutual funds publish prospectuses and periodic reports that include the strategy, fees, and performance data. Holdings are typically disclosed quarterly with a lag, sometimes monthly for certain funds, which provides insight into the portfolio while balancing proprietary management concerns. The fund’s daily NAV is widely reported, but intraday holdings-based estimates are not a feature of the mutual fund model.

What Is an Exchange-Traded Fund?

Core structure and creation-redemption

An ETF is also generally a registered investment company under the 1940 Act, though some commodity and currency products use other structures. The distinctive feature of an ETF is that its shares trade on an exchange throughout the day. Creation and redemption occur in large blocks called creation units between the ETF and authorized participants, commonly abbreviated APs, which are typically broker-dealers. APs deliver a basket of securities and sometimes a small cash component to the ETF sponsor to create new shares, or they return ETF shares to receive the basket in redemption. This in-kind process helps align the ETF’s market price with the value of its underlying holdings and can improve tax efficiency under prevailing regulations.

Pricing, spreads, and premiums and discounts

ETF shares have market prices that change intraday based on supply, demand, and the value of their underlying holdings. Market makers quote bid and ask prices, so investors face a bid-ask spread in addition to any brokerage commissions. An ETF’s market price can trade at a small premium or discount to its net asset value. The arbitrage mechanism, enabled by APs that create or redeem shares, tends to keep these deviations modest for funds with liquid underlying securities. When underlying assets are less liquid or difficult to price, such as certain bonds or international equities, observed discounts or premiums can be larger. In these cases, the ETF’s price often reflects real-time information more accurately than a stale NAV calculation that relies on infrequent or lagged quotes.

Fees and tax considerations

ETFs charge expense ratios similar in concept to mutual funds, though average expense levels vary widely by asset class, strategy, and provider. Investors also face trading costs that depend on spreads, depth of the order book, and any brokerage fees. A notable structural feature is the potential for tax efficiency in many markets because the in-kind redemption mechanism can reduce the need to sell securities and realize capital gains inside the fund. Capital gains distributions are still possible, especially for actively managed strategies, concentrated portfolios, or funds that must transact in cash. Local tax rules vary, so outcomes differ across jurisdictions and fund types.

Transparency and liquidity

Many ETFs, particularly index-tracking funds, publish their holdings daily and provide an intraday estimate of portfolio value, often called an intraday indicative value. This transparency aids market makers in pricing and helps investors assess tracking. Some active ETFs disclose less frequently using approved semi-transparent models while maintaining sufficient transparency for market making. Liquidity in ETFs arises from both the secondary market, where investors trade shares with each other, and the primary market, where APs create or redeem shares as needed. Effective liquidity therefore reflects not only the trading volume of the ETF itself but also the liquidity of the underlying assets.

How Mutual Funds and ETFs Fit Into Market Structure

Primary and secondary markets

Mutual funds operate primarily in a one-tier market. Investors transact with the fund at NAV, and the fund trades the underlying securities as needed to accommodate inflows and outflows. ETFs split activity across two tiers. The secondary market is where most investors trade ETF shares with each other on exchanges. The primary market is where APs exchange creation units for baskets of securities. This two-tier system supports continuous pricing and can concentrate order flow among professional intermediaries that specialize in managing inventory and arbitrage.

Price discovery and NAV

Both mutual funds and ETFs publish NAV per share, usually once daily after the close. For mutual funds, that NAV is also the transaction price for investors. For ETFs, NAV is a reference point rather than the trading price. Price discovery in ETFs occurs intraday as quotes respond to new information, economic releases, and changes in the underlying securities. Deviations between price and NAV can reflect temporary supply-demand imbalances, frictions in valuing underlying assets, or constraints on creation or redemption. Over time, arbitrage and primary market activity tend to realign prices with NAV.

Intermediaries and plumbing

Both vehicles rely on a common set of market infrastructure. Custodians safeguard assets, administrators account for cash flows and valuations, and transfer agents maintain shareholder records. ETFs add market makers and authorized participants to the list of key actors. Market makers quote two-sided prices and manage inventory through hedging and access to the primary market. Authorized participants assemble the specified creation basket, deliver it to the ETF sponsor to create shares, or take delivery in redemption. The specified basket can be representative rather than identical to the full portfolio, which provides flexibility in trading and tax management.

Why These Structures Exist

Both mutual funds and ETFs exist to solve capital formation and investment access problems. They simplify diversification, pool operational costs, and offer professionally managed exposure to asset classes, sectors, factors, or strategies that would be difficult to replicate security by security. Their differing designs reflect trade-offs between certainty of execution price and flexibility of trading, as well as between administrative simplicity and market-based liquidity.

Mutual funds prioritize end-of-day pricing, direct interaction with the fund company, and operational features such as automatic investment plans and precise dollar-level contributions. ETFs prioritize intraday tradability, exchange settlement, and a structure that generally favors tax efficiency where regulations accommodate in-kind redemptions. The coexistence of both allows investors and institutions to select the operational model that best aligns with their constraints, accounting, and execution preferences.

Similarities and Differences at a Glance

- Both pool investor money into a diversified portfolio governed by a prospectus and overseen by a board.

- Both charge ongoing expenses that reduce returns and both distribute income from portfolio holdings.

- Mutual funds transact at end-of-day NAV with the fund company. ETFs trade intraday on exchanges at market prices that may differ modestly from NAV.

- Mutual funds can realize and distribute capital gains from portfolio turnover. Many ETFs reduce capital gains distributions through in-kind redemptions, though distributions can still occur.

- Mutual fund liquidity is provided by the fund itself through issuance and redemption. ETF liquidity is provided by other investors in the secondary market and by APs in the primary market.

Real-World Context and Examples

Example 1: Obtaining broad equity exposure

Consider an investor who wants broad exposure to large-cap United States equities. One avenue is an index mutual fund that tracks a large-cap benchmark. The investor submits a purchase order during the day and receives shares at that day’s closing NAV. There is no intraday price fluctuation to consider, and the transaction is processed by the fund’s transfer agent, with settlement typically on the next business day.

A second avenue is an ETF that tracks a similar benchmark. The investor places a trade through a brokerage account during the trading day. The execution price is the prevailing market price, which reflects intraday moves, bid-ask spreads, and any small premium or discount to NAV. Settlement follows the equity market cycle. In both cases the underlying assets are similar, but the path to ownership and the experience of transacting differ materially.

Example 2: International equities and fair value adjustments

Suppose a mutual fund holds international stocks that closed several hours before the domestic market. The fund may apply fair value adjustments when calculating NAV to reflect information that arrived after the foreign markets closed. This practice seeks to treat entering and exiting shareholders equitably and to reduce dilution from time-zone differences.

An ETF holding the same securities will trade at prices that incorporate new information continuously. If news breaks midafternoon in the domestic market, ETF prices may move even though the foreign listings are not trading. The ETF’s market price can appear to deviate from a stale NAV. In this case, the ETF price often conveys a better real-time estimate of portfolio value than the last reported NAV based on earlier closes.

Example 3: Corporate bond liquidity stress

Fixed income markets can experience stretches of limited quoting depth. A mutual fund in this environment values bonds at observed trades or evaluated prices from pricing services and transacts at NAV at the close. If the fund faces significant redemptions, it may raise cash gradually or sell representative slices of the portfolio, depending on its liquidity management policies.

An ETF holding similar bonds will display an exchange price that reflects market makers’ estimates of executable levels. During stress, discounts to NAV can widen if the reference NAV uses stale or model-based inputs. That discount does not necessarily reflect a defect in the ETF. It can reflect the cost of immediate liquidity in a thin market. As more bonds trade and price discovery improves, discounts typically narrow.

Costs in Practice

Expenses and trading frictions accrue differently between mutual funds and ETFs. Understanding where costs arise helps interpret reported performance.

- Expense ratio: Both structures charge ongoing fees. Expense ratios are deducted from fund assets and are visible in reported net returns.

- Trading costs inside the portfolio: Portfolio turnover incurs commissions, bid-ask spreads, and market impact. These costs are not itemized to shareholders but reduce returns. Strategies with higher turnover generally face higher implicit costs.

- External trading costs: Mutual fund investors do not face bid-ask spreads when buying or selling shares with the fund. ETF investors trade on exchange and thus face spreads and any brokerage fees. Commission-free trading has reduced explicit fees in many accounts, but spreads and execution quality still matter.

- Premiums and discounts: ETF executions at a premium or discount to NAV can incrementally affect the investor’s total cost or benefit relative to the underlying portfolio value.

- Taxes and distributions: Realized gains inside a mutual fund can lead to capital gains distributions. Many ETFs reduce capital gains distributions through in-kind redemptions, but outcomes vary by strategy, turnover, and jurisdiction. Dividends and interest are taxable according to local law for both structures.

Risks and Operational Considerations

Each structure carries specific risks that are distinct from the risks of the underlying assets.

- Liquidity and trading halts: ETFs trade on exchanges, so they are subject to exchange halts and volatility pauses. During halts, orders cannot execute even though underlying securities may be open elsewhere. Mutual funds continue to accept orders for end-of-day processing.

- Premium and discount volatility: ETF prices can deviate from NAV, particularly when underlying markets are closed or illiquid. Oversight by market makers and APs tends to limit persistent deviations, but short-term gaps can occur.

- Tracking difference and error: Index mutual funds and ETFs seek to match a benchmark. Tracking difference refers to realized performance shortfall or surplus relative to the index over time, while tracking error measures volatility of that difference. Expense ratios, cash drag, sampling methods, and trading frictions are common drivers.

- Portfolio transparency and front running: Daily holdings transparency in many ETFs allows precise pricing but can raise concerns about signaling trades in less liquid strategies. Mutual funds disclose holdings with a lag, which can mitigate signaling at the cost of less frequent visibility for investors.

- Fund changes and closures: Both mutual funds and ETFs can merge, liquidate, or change their mandates. ETF closures involve delisting and a final distribution of net asset value. Mutual funds can close to new investors or implement redemption fees during stressed periods according to disclosed policies.

- Operational features: Mutual funds often offer automatic dividend reinvestment at NAV and exact dollar investing. ETF reinvestment usually occurs through broker dividend reinvestment programs, which execute in the market and may not match NAV exactly. Fractional share functionality depends on brokerage systems.

When Structure Influences Outcomes

The choice between mutual fund and ETF structure can influence the path of returns, even for portfolios with similar holdings. Two broad dimensions tend to matter most.

First, execution timing differs. Mutual fund investors receive end-of-day NAV, which can be advantageous for recordkeeping and simplifies execution compared with intraday markets. ETF investors can transact at specific times during the day, which introduces the possibility of price slippage relative to a later NAV but also allows alignment with intraday cash flows or risk management processes. Second, tax treatment can diverge due to the mechanics of in-kind redemptions in many ETFs, which often lower capital gains distributions. The extent of the difference depends on portfolio turnover, concentration, flows, and local tax law.

Beyond these areas, the underlying portfolio and its liquidity profile often dominate. An ETF or mutual fund holding very liquid large-cap equities tends to exhibit small premiums and discounts, tight spreads for ETFs, and limited tracking difference for either structure. In contrast, exposures to less liquid bonds, small-cap stocks, or niche strategies raise the importance of market microstructure, creation basket design, valuation inputs, and liquidity management tools.

Regulatory and Market Developments

The regulatory framework for both vehicles has evolved to reflect their scale and role in markets. In the United States, the ETF Rule codified a consistent approval pathway for most ETFs and standardized elements of creation and redemption. Semi-transparent active ETFs were introduced to allow different disclosure practices while maintaining market making functionality. Settlement cycles have shortened for equities and ETFs, reducing counterparty risk and aligning post-trade processes. Mutual funds have adopted liquidity risk management programs and tools such as swing pricing in some jurisdictions, designed to allocate trading costs more fairly between transacting and remaining shareholders during periods of heavy flows.

These developments highlight the ongoing balance regulators seek between investor protection, market integrity, and innovation. They also underscore that mutual funds and ETFs are not static technologies. Operational and disclosure practices continue to adapt as products broaden across asset classes and as market microstructure changes.

Putting the Differences Into Context

For many broad index exposures, mutual funds and ETFs can deliver economically similar long-run results. Differences in experience show up in the mechanics of trading, cash management, and tax events. For specialized strategies or less liquid assets, structure can have a larger influence on the investor’s realized path because pricing, spreads, and creation and redemption frictions become more pronounced.

Understanding how each vehicle works helps set expectations about order execution, reported performance relative to a benchmark, and the nature of distributions. It also clarifies the roles of intermediaries such as transfer agents, market makers, and authorized participants that handle the operational details behind the scenes.

Key Takeaways

- Mutual funds transact at end-of-day NAV directly with the fund, while ETFs trade intraday on exchanges at market prices that can differ from NAV.

- The ETF creation and redemption process with authorized participants helps align price and NAV and can improve tax efficiency, though outcomes vary by strategy and jurisdiction.

- Costs arise from expense ratios, portfolio trading, and investor trading frictions. For ETFs, bid-ask spreads and premiums or discounts are part of the total cost picture.

- Transparency practices differ. ETFs often disclose holdings daily, supporting real-time pricing, while mutual funds typically report holdings with a lag.

- Both vehicles are integral to modern market structure, offering diversified exposure through pooled portfolios but with distinct operational, pricing, and liquidity characteristics.