Overview

Decentralization is a foundational concept in crypto and blockchain systems. It refers to the distribution of control, decision rights, and failure points across many independent actors rather than concentrating them in a single entity. The term is used frequently, but it covers several distinct layers of a blockchain ecosystem, from how blocks are produced to how upgrades are approved and how infrastructure is operated. Understanding these layers clarifies why decentralization exists, how it fits within broader market structure, and where its practical limits appear in real networks.

This article defines decentralization precisely, outlines the main dimensions on which it is assessed, explains its economic and institutional rationale, and examines real-world events that illustrate benefits and trade-offs. It focuses on fundamentals and does not provide trading strategies or investment recommendations.

What Decentralization Means in Crypto

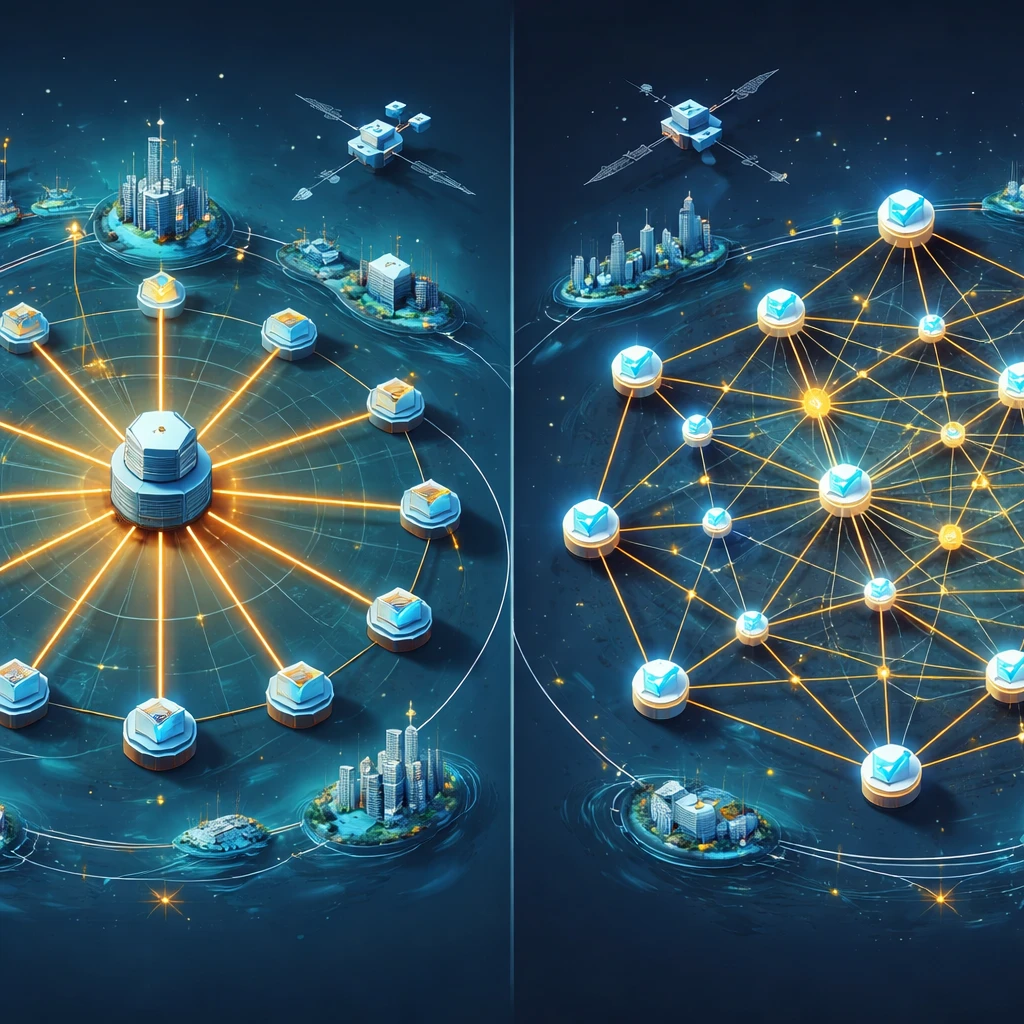

Working definition. In the context of blockchain systems, decentralization is the property that no single party, or small colluding group, can unilaterally control the ledger, censor valid transactions, or change the rules without broad consent. Decentralization is not a binary state. It exists along a spectrum and varies by layer: network connectivity, block production and consensus, client software, governance, token ownership, and supporting infrastructure.

Layers of Decentralization

1. Network and node topology. A decentralized peer-to-peer network has many independently run nodes that relay transactions and blocks without relying on a central hub. Diversity in geography, hosting providers, and connectivity reduces correlated failure. If a large set of nodes depends on one cloud region or one bandwidth provider, the network may be formally decentralized but operationally fragile.

2. Consensus and block production. Consensus defines who proposes and finalizes blocks. In proof-of-work, miners contribute hash power. In proof-of-stake, validators stake assets to participate. Concentration of mining pools or validator sets reduces effective decentralization, even if there are many nominal participants. The ability of a small set to reorganize the chain, censor transactions, or pause the network is central to any assessment.

3. Client software diversity. Users and validators run client implementations that follow protocol rules. If one dominant client has a critical bug, it can split the network or halt block production. Decentralization improves when multiple audited clients exist, when usage is balanced, and when upgrades are adopted through independent implementations rather than a single codebase.

4. Governance and rule changes. Protocol upgrades usually require broad social consensus among core developers, validators or miners, application teams, and users. Processes that allow minority viewpoints to exit via forks while preserving safety for the majority can be considered a form of decentralized governance. If upgrades are effectively determined by one company, foundation, or small committee, governance is centralized regardless of the consensus algorithm.

5. Token distribution and economic power. Ownership concentration can translate into influence over governance and network economics. In proof-of-stake systems, stake concentration can affect validator selection and voting. In application ecosystems, treasury holdings and grant programs can shape development priorities. Decentralization at this layer involves distribution of stake, liquidity across venues, and the presence of checks on concentrated holders.

6. Infrastructure and dependencies. Many applications rely on hosted nodes, APIs, block explorers, and indexing services. If a single infrastructure provider experiences an outage, large parts of the ecosystem may be affected even if the underlying chain is live. This is sometimes termed hidden centralization because it sits above the base protocol but shapes user experience.

7. Application and bridge architecture. Smart contracts, oracles, and cross-chain bridges introduce additional control points. Multisignature arrangements, upgrade keys, and admin roles are practical tools, but they concentrate authority. Decentralized architecture at the application layer seeks to minimize privileged controls or distribute them across independent parties with transparent rules.

Why Decentralization Exists

Decentralization is not pursued for its own sake. It exists to achieve specific institutional and economic goals that are difficult to obtain in centralized systems. The principal motivations include trust minimization, censorship resistance, credible neutrality, and permissionless participation.

Trust Minimization and Credible Neutrality

Crypto networks aim to reduce the need to trust any single organization. A decentralized ledger can be verified independently by any participant who runs a node. If no single group can change balances or invalidate transactions arbitrarily, users rely less on reputation and more on publicly auditable rules. This property supports credible neutrality: the protocol treats participants according to transparent rules rather than discretionary policy.

Resilience and Censorship Resistance

Distributed control reduces single points of failure. If block production is spread across many independent entities, it becomes harder to coerce the system to exclude certain transactions or accounts. Geographic and jurisdictional diversity further raises the cost of censorship. There is no guarantee of perfect resistance, but the cost and coordination required to disrupt a decentralized network can exceed the incentive to attempt it.

Open Access and Permissionless Innovation

Anyone can read the ledger, submit transactions, and, subject to protocol rules, participate in validation. Developers can deploy contracts without gatekeepers, which encourages experimentation and composability. This openness changes market structure by allowing new entrants to build on shared infrastructure without negotiating with a platform owner.

Economic Security and Incentive Alignment

Consensus mechanisms translate economic resources into security. In proof-of-work, an attacker must control substantial hash rate to rewrite history. In proof-of-stake, an attacker must control and risk slashed stake. Decentralized participation spreads both security provisioning and the distribution of rewards, aligning the interests of many participants with network integrity.

How Decentralization Fits into Market Structure

Crypto markets are built around shared ledgers that multiple economic actors use simultaneously. Decentralization influences how power and revenue are distributed across these actors and how they coordinate.

Participants and Power Distribution

Validators and miners. These actors produce blocks and earn protocol rewards and fees. Their concentration affects not only security but also bargaining power with other ecosystem participants. For instance, a few dominant mining pools or staking providers can shape fee dynamics or policy preferences.

Node operators and gateways. Full nodes enforce rules by verifying blocks and transactions. Light clients and remote procedure call gateways connect users to the network. If many users access the chain through a small number of gateways, those gateways become de facto chokepoints, even when they do not produce blocks.

Core developers and client teams. Protocol development is typically organized through open repositories and public discussion, but practical influence is often concentrated among maintainers and researchers with deep expertise. Diversity across independent teams and the ability to propose competing implementations helps balance influence.

Exchanges, custodians, and wallets. Centralized exchanges and custodians aggregate user balances and often control substantial stake in proof-of-stake systems. Their operational policies can affect governance outcomes, staking distribution, and transaction propagation. Non-custodial wallets, by contrast, leave control with users but may still rely on centralized infrastructure for data.

Service providers and data layers. Indexers, oracles, bridges, and analytics firms connect blockchains to external data and other networks. Each service introduces assumptions about who can change data or pause functionality. Market structure therefore includes a stack of dependencies that are partly decentralized and partly centralized.

Coordination Mechanisms

Consensus protocols. These define how blocks are accepted and finalized. Their parameters, such as block time and validator selection, shape incentives and the cost of collusion.

Fee markets. Scarce block space is allocated by fees. Design choices, such as base fees with burns or priority fees, influence user costs and validator revenue. Fee mechanics can reduce manipulation risk or create incentives for extractive behaviors.

Governance processes. Off-chain discussion, on-chain votes, and informal social norms all play roles. The ability to exit via a fork serves as a discipline on centralized decision making, but it also introduces fragmentation risks.

Regulatory Interface and Centralization Pressures

External pressures can push networks toward or away from decentralization. Compliance requirements may encourage concentration in a few regulated intermediaries. Conversely, regulatory uncertainty can prompt users to rely on self-custody and open-source tooling. Jurisdictional diversity among validators and infrastructure providers mitigates the risk that one legal regime can impose policy across the entire network.

Measuring Decentralization

No single metric captures decentralization across all layers. Researchers therefore use a set of indicators and interpret them together.

Quantitative Indicators

- Validator or miner concentration. Shares of block production by entity or by the top N participants. A common heuristic is the minimum number of entities required to reach a controlling share of block production.

- Nakamoto coefficient. The size of the smallest set of entities whose combined power can compromise a given function, such as consensus or governance. This coefficient can be calculated for different subsystems.

- Client diversity. Distribution of validators across independent client software, measured by percentage share. Concentration in a single client increases correlated failure risk.

- Geographic and provider diversity. Locations of nodes and their hosting providers. Overreliance on a single cloud provider or country increases policy and outage risk.

- Ownership distribution. Token holdings across addresses, adjusted for entities that control multiple addresses. In proof-of-stake systems, effective stake distribution is more relevant than raw token counts.

- Governance participation. Number of voters, turnout by stake and by unique entities, and concentration of proposal power or multisignature control over treasuries.

- Dependency mapping. Share of applications that rely on specific APIs, indexing services, or oracles. A high dependency on a single service indicates centralization at the infrastructure layer.

Qualitative Considerations

- Sybil resistance. A large number of apparent participants may mask control by a single actor. Effective decentralization depends on independence, not nominal counts.

- Cartel dynamics. Even with many participants, explicit or tacit collusion can arise. Protocol design can raise the cost of collusion, but social and economic incentives matter.

- Social consensus and exit. The ability of stakeholders to refuse upgrades or split the chain shapes governance power. Community norms, transparency, and public review processes are integral components of decentralization.

- Operational maturity. The presence of runbooks, public incident reports, and standard processes for key management and client upgrades can reduce unintentional centralization during crises.

Trade-offs and Costs of Decentralization

Decentralization improves robustness and reduces reliance on trusted parties, but it introduces costs and trade-offs that appear in performance, coordination, and user experience.

Performance and Throughput

Coordinating among many independent validators increases communication overhead. Finality often takes longer, and throughput is constrained by how quickly messages can be propagated and verified. Optimizations, such as aggregation and sharding, can improve throughput, but they do not eliminate the fundamental trade-off between broad participation and low-latency settlement.

Resource Costs

Proof-of-work consumes significant energy to secure the network. Proof-of-stake reduces energy use but introduces capital lockup and the need for robust slashing and monitoring infrastructure. Both designs require investments from participants to maintain security, and both can experience centralizing pressures through economies of scale.

Complexity and Governance Friction

Decentralized systems evolve through proposals, public discussion, and phased deployments. This reduces the risk of unilateral errors but slows iteration. When critical bugs appear, coordinating a safe response without centralized authority is challenging. Emergency controls can address acute problems, but they also concentrate power and must be evaluated carefully.

User Experience and Safety

Self-custody improves independence but places responsibility for key management on users. Richer wallets and account abstraction can mitigate risks, yet the absence of a centralized recovery option raises the cost of mistakes. For many users, gateways and custodians provide convenience, creating a layered market structure where decentralization at the base coexists with centralized services at the edge.

Real-world Context and Examples

Several well-documented incidents illustrate how decentralization works in practice, where it succeeds, and where hidden centralization can appear.

Client Monoculture and Network Stability

In November 2020, an outage at a major Ethereum infrastructure provider disrupted access for many applications. The base chain continued to produce blocks, but wallets and services that depended on a single provider could not fetch data or send transactions. The episode underscored a distinction between protocol-level liveness and application-level availability. It highlighted the value of client diversity, redundant gateways, and local nodes in reducing correlated failures.

Earlier, in March 2013, the Bitcoin network experienced a temporary chain split triggered by a software incompatibility related to database handling. Nodes running different versions diverged until miners coordinated to return to a common chain. The event demonstrated how client heterogeneity can both create and resolve incidents, and why coordinated but transparent processes are integral to decentralized recovery.

Validator Concentration and Policy Pressure

After the transition of Ethereum to proof-of-stake in 2022, public data showed a large share of validating stake managed by a handful of providers, including staking pools and exchanges. Around the same period, some relays and validators began filtering transactions associated with sanctioned addresses, reflecting compliance choices by service operators. The base protocol permitted all valid transactions, yet relay-level filtering revealed how centralization at intermediate layers can influence ordering and inclusion. The community response included promoting relay diversity, monitoring inclusion rates, and encouraging adoption of non-filtering infrastructure.

Network Halts and Governance Control

In multiple incidents from 2021 onward, the Solana network experienced periods of instability that led to validator coordination to pause and restart the network after addressing the underlying issue. The ability to coordinate a restart helped restore functionality, but it also showed that a relatively small validator group could, in practice, pause the chain. That property is not inherently negative or positive, but it is relevant when analyzing where authority resides and how it might be exercised during stress.

In October 2022, following a large exploit of a cross-chain bridge associated with BNB Chain, validators paused the network to apply a patch and address the incident. This action again illustrated the trade-off between rapid coordinated response and decentralized control. The episode offered a clear example of governance power in a system with relatively concentrated validator sets.

Stablecoins and Off-chain Dependencies

Stablecoins introduce centralized components because they reference assets held off-chain. Issuers can often freeze specific addresses or blacklist transactions to comply with legal requirements. In 2022, following sanctions on certain services, some stablecoin issuers restricted balances at specified addresses. Even when a base chain is censorship resistant, assets that depend on external legal entities may embed centralized control. This interplay between on-chain neutrality and off-chain constraints is essential to understanding the practical reach of decentralization.

Forks and Social Consensus

Contentious upgrades and incident responses occasionally lead to chain splits. The 2016 Ethereum hard fork after The DAO exploit is a well-known example. One chain continued with a state change to reverse specific effects of the exploit, while another preserved the original history. Both chains followed clear rules, but the communities diverged on governance values. Forks demonstrate that decentralization includes a social layer: market participants choose which rules to follow, and the possibility of exit disciplines concentrated power.

Common Misunderstandings

Decentralization is not absolute. Every system contains some centralized components, whether at the infrastructure layer, in governance coordination, or in external dependencies like oracles. The question is where centralization resides and how much power it confers.

More nodes do not always mean more independence. If many nodes are controlled by a single organization or run identical setups in a single cloud region, the system may be vulnerable to correlated failures. Effective decentralization requires independence of control, funding, and operational decisions.

Base-layer decentralization does not automatically extend upward. An application running on a decentralized chain can still rely on centralized price feeds, admin keys, or hosted infrastructure. Analysis needs to follow the full dependency graph.

Decentralization is not an end in itself. It is a design choice that trades off performance and coordination speed for robustness and neutrality. The appropriate degree of decentralization depends on the function a system aims to perform and the risks it must withstand.

Practical Implications for Users and Builders

The degree and location of decentralization change the trust assumptions participants make. A few practical dimensions often considered in technical assessments include the following.

- Assumed trust set. Which actors must be trusted not to collude or fail, and what is their independence?

- Upgrade and emergency powers. Who can change parameters, deploy patches, or pause contracts? Under what processes and public scrutiny?

- Exit options. If there is disagreement, can participants safely continue on an alternative client, deny an upgrade, or rely on a fork without loss of funds?

- Operational concentration. How dependent is the system on a single provider for nodes, indexing, or oracles? Are there viable alternatives?

- Economic concentration. How distributed are stake and liquidity across entities, and how does that distribution affect incentives?

These considerations are not prescriptive. They clarify the nature of the system and the kinds of risks that may arise during stress, upgrades, or regulatory change.

How Decentralization Evolves Over Time

Decentralization is dynamic. As networks scale, new centralization pressures emerge. Economies of scale in staking or mining, professionalization of infrastructure, and regulatory requirements can concentrate control. At the same time, technological improvements can reduce barriers to independent participation. Examples include lighter clients, improved peer-to-peer networking, better key management, and more diverse client implementations.

Ecosystems often evolve from more centralized early stages, where a small core team drives development, to more distributed stewardship as software matures and community capacity grows. Treasury decentralization and the emergence of independent clients and research groups generally increase resilience. Conversely, growth in total value secured can raise the stakes of coordination failures, placing new weight on incident response and monitoring.

Analytical Framework for Case Evaluation

When examining any blockchain or application, a structured approach helps locate the sources of control and risk. A simple framework involves three steps.

- Map the layers. Identify consensus, clients, governance, token distribution, infrastructure, and external dependencies like oracles or legal entities.

- Quantify concentration. Use available data on validator shares, client usage, hosting concentration, and governance turnout. Note where data is uncertain or where entities may control multiple addresses.

- Evaluate failure modes. Consider censorship scenarios, correlated outages, upgrade disputes, and key compromise. Review historical incidents and published postmortems.

This type of analysis does not produce a single score. Instead, it reveals trade-offs and helps explain how a system might behave under stress.

Broader Economic and Institutional Context

Decentralization alters the boundaries of institutions. Traditional finance relies on legal enforcement and centralized operators for settlement finality. Blockchains move some of that assurance into cryptographic verification and economic incentives. This shift changes the roles of intermediaries. Some functions remain centralized by necessity, such as fiat custody or identity verification. Others become open and programmable, such as market making through automated contracts.

Market structure reflects these boundaries. Centralized entities often handle onboarding, fiat interfaces, and custody for users who prefer convenience. Decentralized infrastructure secures settlement and enables permissionless development. Competition and cooperation occur across the boundary, with bridges, oracles, and standards coordinating activity.

Limitations and Open Questions

Even highly decentralized systems face challenges. Long-range attacks in proof-of-stake require solutions such as weak subjectivity checkpoints. Cross-domain composability introduces security dependencies across chains and rollups. Formal verification helps reduce software bugs, but residual risk remains. Governance processes must balance inclusiveness, expertise, and responsiveness under time pressure. None of these questions has a fully general solution, which is why empirical observation of operating networks is valuable.

Conclusion

Decentralization distributes control and verification across many independent actors to reduce reliance on trusted intermediaries, increase resilience, and support neutral public infrastructure. It operates across several layers, and its degree varies among networks and over time. Measuring decentralization requires multiple indicators and attention to practical dependencies, not only protocol design. Real-world incidents reveal both strengths and limits, and they show that decentralization is most meaningful when paired with transparent processes, client diversity, and careful attention to infrastructure.

Key Takeaways

- Decentralization is multidimensional, spanning consensus, clients, governance, token distribution, and infrastructure dependencies.

- Its purpose is trust minimization, credible neutrality, resilience to censorship, and permissionless participation, not performance maximization.

- No single metric captures decentralization; analysts combine quantitative indicators with qualitative assessment of independence and failure modes.

- Real incidents demonstrate hidden centralization, such as reliance on a single infrastructure provider or concentrated validator sets.

- Decentralization is dynamic and path dependent; design choices and market forces continuously reshape where control resides.