Introduction

Crypto exchanges are the primary marketplaces where digital assets are priced, traded, and transferred between participants. They connect buyers and sellers, maintain records of balances, and coordinate settlement. Some operate with centralized infrastructure and custodial services. Others run as decentralized protocols on public blockchains. Understanding what exchanges do and how they fit into the broader market structure is foundational to understanding crypto markets.

What Is a Crypto Exchange

A crypto exchange is a platform or protocol that facilitates the exchange of one digital asset for another, or for fiat currency such as dollars or euros. At a basic level, an exchange manages two functions. It matches counterparties who want to trade at compatible prices and it arranges settlement so that ownership is transferred correctly.

In centralized exchanges, a private company runs the technology stack, holds customer deposits in custodial wallets, operates an order book, and credits or debits internal accounts when trades execute. In decentralized exchanges, smart contracts on a blockchain coordinate trades directly from users’ wallets, with settlement written to the chain itself.

Why Exchanges Exist

Exchanges exist because market participants need price discovery, liquidity, and dependable settlement. Without a centralized venue or a coordinating protocol, buyers and sellers would have to find one another bilaterally, which is inefficient and opaque. Exchanges aggregate orders and liquidity, which lowers search costs and helps produce a market price that reflects available information.

Exchanges also provide a standardized interface for deposits, withdrawals, and order entry. On the operational side, they centralize or automate risk controls, record keeping, and fee collection. This set of functions is similar to traditional securities and commodities venues, adapted to the properties of blockchain-based assets.

Where Exchanges Fit in the Market Structure

Crypto exchanges sit at the core of the secondary market for digital assets. They are the main locations for price discovery, where the prevailing price of assets like BTC or ETH is determined at each moment. Liquidity providers and market makers quote prices and maintain order books or liquidity pools. Arbitrageurs move prices toward consistency across venues by trading where assets are mispriced relative to one another.

Upstream of exchanges are token issuers and primary distribution channels, such as network launches and token generation events. Downstream of exchanges are custodians, analytics providers, wallets, and applications that rely on market prices and the ability to transfer assets on-chain.

In practice, a small set of large exchanges often concentrates a significant portion of volume in major asset pairs. Smaller exchanges and decentralized protocols contribute additional liquidity that can be accessed directly or via aggregators.

Centralized Exchanges

Centralized exchanges, often abbreviated as CEXs, are operated by companies that provide a web interface, mobile apps, and programmatic access via APIs. They typically hold customer funds in a mix of cold wallets that are offline and hot wallets that service withdrawals. Internally, they maintain a ledger of customer balances and a matching engine that pairs buy and sell orders.

Order books on a centralized exchange list limit orders that specify price and quantity. When a new order arrives, the matching engine compares it against existing orders and executes trades when prices cross. The exchange credits and debits internal balances in real time. Blockchain settlement occurs only when a customer deposits to or withdraws from the exchange. This design allows very fast matching and low-latency updates, since most activity happens off-chain inside the exchange’s systems.

Centralized exchanges usually offer multiple asset pairs, such as BTC against USD or stablecoins, and may support spot markets and derivatives. Participation often requires identity verification due to regulatory compliance obligations. Fiat on-ramps and off-ramps are commonly integrated through banking partners, which introduces additional operational considerations, such as wire processing times and transfer limits.

Decentralized Exchanges

Decentralized exchanges, or DEXs, are sets of smart contracts that users interact with directly from non-custodial wallets. There is no centralized custodian of user funds. Settlement occurs on the blockchain, and trade execution is constrained by the throughput and fee dynamics of the underlying network.

Many popular DEXs use automated market makers, or AMMs. In an AMM, liquidity providers deposit two assets into a pool. The pool’s pricing function adjusts the relative price based on the current ratio of assets in the pool. A swap changes that ratio and therefore the price. If a large order pushes the price away from the wider market, arbitrageurs trade against the pool to restore alignment. AMM design shifts the challenge of maintaining an order book into the design of a pool and its pricing formula.

Other DEXs implement on-chain order books or hybrid models that store orders off-chain while settling on-chain. Since DEX trades write to the blockchain, users pay network fees and must consider confirmation times. The transparency of on-chain settlement provides public data on volumes and pool balances, although privacy is limited by the public nature of the ledger.

Hybrid and Alternative Designs

Between traditional centralized models and fully decentralized protocols, several hybrid designs exist.

- Centralized matching with on-chain settlement. Orders are matched by a centralized service, but trades settle through smart contracts.

- Layer 2 exchanges. Matching and netting occur on a scaling network that periodically commits state to a base chain, which can reduce fees and increase throughput.

- Request-for-quote and aggregator services. These route orders across multiple DEX pools or market makers to find a composite price and reduce slippage.

These architectures attempt to balance speed, cost, and transparency.

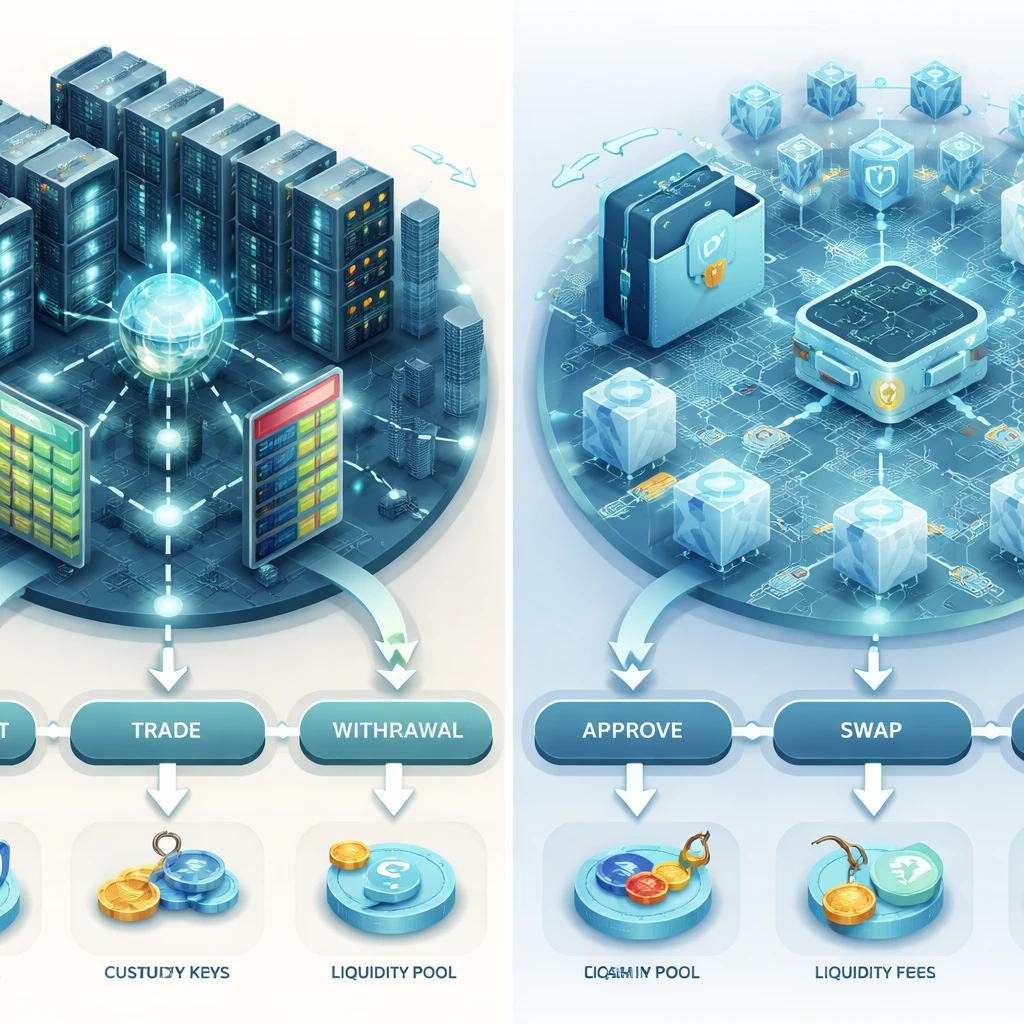

How a Trade Works on a Centralized Exchange

Consider a participant who wants to acquire a crypto asset using fiat currency.

- Account setup and verification. The participant completes identity checks and links a bank account or card if fiat funding is required.

- Deposit. The participant transfers funds to the exchange. The exchange credits an internal balance once funds are available.

- Order entry. The participant submits a market order or a limit order. A market order seeks immediate execution at the best available prices. A limit order specifies a maximum buy price or minimum sell price.

- Matching and execution. The exchange’s matching engine pairs the order with compatible orders in the order book. Execution can occur across several price levels depending on size and liquidity.

- Post-trade balances. The exchange updates internal ledgers to reflect the trade. The participant now has a new asset balance inside the exchange.

- Withdrawal. If the participant withdraws to a personal wallet, the exchange signs and broadcasts a blockchain transaction. Blockchain settlement occurs once the network confirms the transaction.

Throughout this process, trades typically finalize quickly in the exchange’s internal system, while blockchain settlement time for withdrawals depends on network conditions.

How a Trade Works on a Decentralized Exchange

A comparable flow on a DEX looks different.

- Wallet connection. The participant connects a non-custodial wallet to the DEX interface.

- Approval. For many tokens, a one-time approval transaction is needed to allow the DEX contract to move tokens on behalf of the wallet.

- Quote and slippage controls. The interface estimates the output amount and shows a minimum expected amount after slippage tolerance.

- Transaction submission. The participant signs a transaction that calls the DEX contract to perform the swap. Network fees are paid in the chain’s native token.

- On-chain settlement. Miners or validators include the transaction in a block. Once confirmed, the wallet’s balances reflect the swap. Finality depends on the chain’s consensus and block time.

This model provides transparency and self-custody, while introducing network fee variability and the possibility of transaction reordering by block producers.

Assets, Listings, and Trading Pairs

Exchanges list trading pairs that define what is being traded against what. A pair such as ETH and USD treats USD as the quote currency and ETH as the base. Stablecoins often serve as the quote currency for a wide range of pairs. On a DEX, the analogous idea is a liquidity pool composed of two assets, such as ETH and a stablecoin.

Listing decisions on centralized exchanges involve technical integration, legal review, compliance considerations, and liquidity expectations. Delisting can occur for low activity, security concerns, or regulatory reasons. DEX listings are more permissive because anyone can create a pool, but liquidity and smart contract quality vary widely. In some cases, the same token symbol may represent distinct assets across chains or wrapped representations, which makes careful identification important.

Bridged or wrapped tokens introduce an additional dependency on the bridge operator or the wrapping contract. If a bridge is compromised, the wrapped asset can diverge from the value of the original asset on its home chain. This is a structural distinction from native assets whose supply and consensus live on their original networks.

Fees and Costs

Fees influence the realized cost of trading.

- Trading fees. Centralized exchanges often use maker and taker fees. A maker adds liquidity by placing a limit order that rests on the book, while a taker removes liquidity by crossing the spread. Fee tiers can depend on monthly volumes.

- Spreads and price impact. The cost of a trade is also affected by the bid and ask spread and by the effect of a large order on available liquidity.

- Network fees. DEX users pay blockchain transaction fees. Costs rise when the network is congested. Withdrawals from centralized exchanges also incur network fees when assets are sent on-chain.

- Funding and other charges. Derivatives venues may charge funding payments or settlement fees. These are structural features of specific products rather than strategy guidance.

Understanding the fee schedule and the role of spreads and price impact is part of understanding how exchanges function economically.

Custody, Settlement, and Finality

Custody is the central difference between centralized and decentralized models. In a centralized exchange, the exchange holds the private keys that control customer deposits. Customers see internal balances credited to their accounts. In a decentralized exchange, users control their own keys and interact with contracts that settle directly on-chain.

Settlement timing differs as well. Centralized exchanges settle trades instantly on internal ledgers. On-chain settlement and finality occur only when funds are withdrawn. Decentralized exchanges write every trade to the blockchain, which provides auditable records but exposes trades to network congestion and confirmation risk. Some blockchains have probabilistic finality, where confidence increases with additional blocks. Others provide deterministic finality within a fixed time once a block is finalized by the consensus protocol.

Several centralized exchanges publish proofs of reserves that aim to demonstrate that on-chain assets back customer liabilities. These disclosures vary in scope and rigor. They are not the same as an audit of internal controls and do not by themselves prove the absence of liabilities elsewhere in the corporate structure.

Market Integrity and Regulation

Crypto exchanges operate within legal and regulatory frameworks that vary by jurisdiction. Activities can include money transmission, custody, and operation of a trading venue. Compliance obligations often involve identity verification, sanctions screening, anti-money laundering procedures, and transaction monitoring. Some jurisdictions license exchanges, while others restrict certain activities or products.

Market integrity programs monitor for behaviors that undermine fair pricing, such as spoofing, layering, and wash trading. The degree of surveillance and enforcement differs across venues. In decentralized markets, transparency and public data provide one layer of oversight, while formal surveillance is limited since there is no centralized operator. Analytics firms and community participants often monitor on-chain behavior.

Historical events illustrate categories of risk rather than offering predictions. The collapse of Mt. Gox in 2014 highlighted security and operational vulnerabilities in custodial exchanges. The failure of FTX in 2022 showed the consequences of poor governance and misuse of customer funds within a centralized corporate structure. These episodes motivate ongoing attention to custody architecture, segregation of assets, and internal controls.

Security Risks and Operational Considerations

Security risks differ across exchange types but are present in both.

- Custodial risk. Centralized exchanges concentrate assets in wallets they control. Compromise of hot wallets, operational errors, or mismanagement can create losses. Cold storage frameworks, multi-signature arrangements, and withdrawal controls are common mitigations.

- Smart contract risk. DEX users rely on code. Bugs in contracts can be exploited. Formal verification, audits, and time-tested implementations reduce but do not eliminate risk.

- Oracle and liquidity risk. Some DEXs depend on pricing oracles. If an oracle is manipulated or delays occur, pools can be mispriced. Shallow liquidity increases price impact for larger trades.

- Network-level risk. Congestion, reorgs, and validator failures can delay settlement or create temporary uncertainty. Cross-chain bridges add additional attack surfaces.

- Operational risk. Interfaces can malfunction, APIs can break during high load, and support systems can lag. During volatile periods, both centralized and decentralized venues may experience degraded performance.

Security is a process that spans code, infrastructure, and governance. In custodial systems, business continuity and asset segregation are material concerns. In non-custodial systems, upgrade procedures, admin keys, and governance controls are equally significant.

Data, APIs, and Access

Access to market data and trading connectivity shapes how participants interact with exchanges. Centralized exchanges provide REST and WebSocket APIs that deliver order book data, trades, and account updates. Depth of book snapshots and incremental updates allow market participants to reconstruct the order book in real time. Rate limits and authentication requirements vary by venue.

DEX data is available directly from the blockchain and from indexers that parse on-chain events. Pool states, swap events, and liquidity positions can be analyzed publicly. Latency is higher than an internal matching engine because updates occur per block. The transparency of on-chain data enables independent verification of volumes and liquidity, with the caveat that interpretation requires care when transactions are pending or replaced.

Case Study: A Day of High Volatility

Consider a day when a major macro event triggers rapid price changes across crypto assets. On centralized exchanges, order books may thin as market makers widen quotes or reduce size. The matching engine processes a surge of market orders, which can result in larger price impact for aggressive trades. Some exchanges implement risk controls such as rate limits or temporary protective pauses at the instrument level, which can slow or prevent extreme order flow from overwhelming systems.

On decentralized exchanges, network congestion typically raises transaction fees. Users who set lower fees may see transactions delayed or dropped in favor of higher fee transactions. Slippage protection becomes relevant as pool prices move rapidly between the time a transaction is submitted and when it is mined. Arbitrageurs compete to realign pool prices with broader market prices, paying higher fees to prioritize their transactions. Cross-chain routes depend on multiple networks and bridges, which can introduce additional delays.

In both settings, quoted prices represent the current state of liquidity and information. Execution quality depends on the interaction between order size, market depth, and system performance during stress.

Common Misconceptions

- Owning assets on a centralized exchange is the same as holding assets in a personal wallet. In a custodial model, the exchange controls the private keys and credits an internal balance to the customer. Personal wallets hold private keys directly.

- Decentralized exchanges remove all costs. On-chain trading imposes network fees and price impact, and some protocols charge explicit swap fees.

- All volume is interchangeable across venues. Volume quality depends on market integrity, the presence of liquidity providers with real capital, and the design of the venue.

- All tokens with the same symbol are identical. Tokens can be native to a chain or bridged representations on another chain, which introduces additional dependencies and risks.

- On-chain transparency means perfect information. Mempool dynamics, private order flow, and pending transactions create information asymmetries even in transparent systems.

How Exchanges Continue to Develop

Exchanges evolve as networks scale and as regulation, user expectations, and technology advance. Several areas receive sustained attention. Cross-chain settlement and bridging seek to make liquidity more composable across networks. Layer 2 systems aim to reduce costs and increase throughput. Auditable reserve disclosures, stronger governance practices, and improved wallet security aim to address past failures in custody and risk management. None of these trends remove the fundamental trade-offs among speed, cost, privacy, and transparency, but they illustrate the direction of ongoing engineering and policy work.

Real-World Examples and Context

Examples help ground the concepts without implying a judgment about any venue. Global centralized exchanges such as Coinbase, Kraken, and Binance operate order books, hold customer funds, and support fiat on-ramps subject to local regulations. Decentralized exchanges such as Uniswap, Curve, and SushiSwap run smart contracts that manage pools and allow swaps directly from wallets. Perpetual futures DEXs such as dYdX and GMX illustrate on-chain or hybrid derivatives trading. Each model embodies distinct choices about custody, execution, and transparency.

Historical incidents illustrate how design and governance choices matter. The Mt. Gox collapse revealed operational and security shortcomings in early custodial infrastructure. The FTX failure showed that internal controls and the segregation of customer assets are central to any custodial venue’s safety. On the decentralized side, exploits in DeFi protocols, such as vulnerabilities in unaudited contracts or oracle manipulation, show that smart contract correctness and dependency management are critical.

Practical Considerations Without Strategy

Operational details influence how exchanges function, independent of any trading approach. Withdrawal processing times depend on both the exchange’s internal batching and the blockchain’s current load. Deposit credit policies differ by asset, since some blockchains require a certain number of confirmations before crediting funds. Maintenance windows for upgrades can temporarily restrict deposits or withdrawals. Network reconfigurations, hard forks, or chain halts require exchanges to adjust integration, sometimes suspending transfers until the network is stable.

Interfaces also vary. Some venues provide advanced order types such as stop orders or post-only limit orders. DEX interfaces generally focus on swaps and liquidity provision, with routing across pools to reduce price impact. API reliability, documentation quality, and historical data access determine how easily external systems can integrate with an exchange.

Concluding Perspective

Crypto exchanges are the infrastructure that turns distributed assets into tradable markets. Centralized models concentrate custody and execution inside a company’s systems, which enables speed and fiat integration but introduces counterparty and governance risk. Decentralized models shift custody and settlement on-chain, which increases transparency and self-custody while inheriting the constraints and risks of blockchain networks. Both sit within a broader ecosystem that includes token issuers, wallets, custodians, liquidity providers, and data services. A clear grasp of what exchanges do, how they operate, and how they differ is essential for understanding the structure of crypto markets.

Key Takeaways

- Crypto exchanges coordinate price discovery, liquidity, and settlement for digital assets, either through centralized custodial systems or decentralized smart contracts.

- Centralized exchanges match orders off-chain and hold customer assets, while decentralized exchanges execute and settle trades on-chain from user-controlled wallets.

- Fees, spreads, network costs, and liquidity depth shape the economic reality of trading across both models.

- Security and governance risks differ by design, ranging from custodial failures to smart contract and oracle vulnerabilities.

- Exchanges operate within broader legal and technical environments that influence listings, data access, and the reliability of deposits, withdrawals, and execution.